From driving for Uber to crafting email scams, the ways people earn money are even more numerous than the ways labor has been studied and documented. The changing nature of work is the subject of Re:Working Labor, a multi-part project at School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) directed by Daniel Eisenberg (Professor, Film, Video, New Media and Animation) and Ellen Rothenberg (Adjunct Professor, Fiber and Material Studies). As artists whose work deals with issues of labor, state violence, and social inequality, they are well-suited to the project as the inaugural faculty fellows in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) Institute for Curatorial Research and Practice. After a two-day symposium in fall 2018, a rich public programming series, and just as the fall 2019 exhibition at SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries was coming to close, I sat down with Daniel and Ellen to talk about the process of pulling together the large-scale collaborative project, why academics in Europe are more political than their American counterparts, and what to do about corporate funding in the arts.

Leah Gallant: This exhibition is part of the work that came out of an interdisciplinary research group that you participated in at re:work, or the IGK Work and Human Life Cycle in Global History program at Humboldt University in Berlin. What was that experience like? Why is an interdisciplinary approach to theorizing and organizing around labor necessary, and what role do artists play?

Ellen Rothenberg: My experience at the school has been really interdisciplinary. I began teaching in performance, then I taught in sculpture, then I taught in arts administration, video, writing, and fiber. My work was appropriate to working and teaching across boundaries and media. I think the other aspect of this was that both Dan [Eisenberg] and I had had considerable experience living and working in Europe, and so we were also interested, in a moment of nationalism and nationalist regression, in having a global event. We wanted to involve people from across Chicago from different institutions, but also bring artists like Ibrahim Mahatma from Ghana, Prabhu Mohapatra from India, and connections that Dan made as a fellow at re:work in Berlin. My own work is predicated on a certain kind of generosity from people who have other areas of expertise, whether it’s archivists, forensic scientists, metalworkers, or people who are associated with the oldest quarry in New England. Their skills and experience inform my own interest and work. I’ve found that if you’re seriously interested, people are very generous with their time and knowledge.

Daniel Eisenberg: I never went to art school, I went to university. I was trained in research, writing, and thinking more broadly. My practice has always been research-based, and Ellen’s as well. Some [people at re:work] were skeptical about non-research based practices, and I had to produce a presentation to talk about the uses of sensual knowledge, or how knowledge can reside in the body or senses in a way that’s outside of language or research practice. It’s a different kind of research practice.

ER it was very interesting to see Dan present at re:work, and to see the reactions of historians, anthropologists, and sociologists. These are people who have spent their entire lives looking at work and life cycle. Dan shared his work as it exists, which doesn’t resemble a documentary, a form they would be accustomed to. It’s a form of filmmaking that asks you to have an experience, and that requires your attention. Afterwards, there was silence, and there was this discussion about the fact that he had brought them into the factory. I was shocked, because I assumed that they had been there — but most of their work was taking place in libraries and archives, and so I think that the fact that he produced an experience for them was kind of radical.

DE Most people saw bringing in art as an opening and unveiling of possibilities. At the final conference at re:work, I’m working on a very large project of three factories, and I showed 15 minutes from each, and the other fellows loved it. The conversation there blew me away, because I could talk about all the things that motivated the work and the research. I had my equal interlocutors, and it was so exciting to me.

ER I think also that a lot of the people involved with re:work are really political.

DE They’re not afraid to be leftists. This illusion of neutrality doesn’t really exist in Europe. Political parties are very upfront, and institutions and departments are very upfront. People wear their politics openly.

ER They’re engaged in not only research, but also political activism. For example, one of the re:work team was very involved with the refugee crisis, and was very helpful to me by introducing me to this very large group of immigrants living in Tempelhof airport in Berlin. That came from 3 years of her being a citizen activist with a collective group to support the influx of refugees in a manner the government wasn’t prepared to do. I ended up showing this project at the Spertus Institute in Chicago, and at James Gallery at the CUNY graduate center.

ER The other thing that I think is very unique to Europe is the approach to personal relationships and institutional relationships. They don’t see anything as a one-off arrangement. It’s a lifetime relationship, and that allows things to develop in a much different timeframe.

DE It’s a different orientation, a communal orientation, and they’re also very serious around scholarship and publication and outcomes. Whereas here in the United States, it’s like a machine, you have your fellowship, you get spit out. The next person comes in, then gets spit out.

ER The pace is so accelerated here. But also, with what’s available in the U.S. to artists and scholars, it’s much more competitive because there’s so much less. We’ve had the benefit of seeing other models, and I think those models influenced the way we thought about our curatorial fellowship at SAIC, and that’s what led us to first think about the symposium as a way of creating a conversation, of bringing people together, but also as the potential for it to lay a foundation for the exhibition. You rarely have that opportunity. If you’re given the opportunity to have a show, usually that’s the whole opportunity.

Leah Gallant: I’m curious about issues with translating a lens of labor rights and issues into the reality of an institution. For example, how did artist compensation work for those participating in the Sullivan Galleries show? W.A.G.E. is a New York-based organization that aims to establish equitable labor practices between institutions and artists. One of their projects is the W.A.G.E. Certification program, which guarantees that institutions meet their standards for compensating artists beyond material costs or purchases of work. What do you think of W.A.G.E. — do you see a future in which artists are paid for their work? Were artists in this show paid according to W.A.G.E. standards?

DE We are artists, and we understand how that works, so what we basically said to artists participating in the Re:working Labor exhibition is, we don’t have that big a budget, but we do have a lot of resources. We have students, we have space, and we have equipment. We worked mostly with people who we already had relationships with, and we said, this is what we’ve got, give us a proposal and a budget and then we can start from there. Include in your budget your honorarium, your materials, and what you need, and let’s figure out what we can do.

ER Some of the artists are people used to very big budgets, so this was a very big shift from how a museum might support them. Ibrahim Mahatma, for example, works at a very different scale. He’s also very committed to education. He had met with our SAIC students in Berlin, during our summer program, in 2017, and had talked about his work. He was very, very open about the logistics, the financial burdens, how he works with people, what his values are, this art education center that he was building in the north of Ghana. Even as a young 30-year-old artist, he was already committed to education, and he’s the beneficiary of a really great education, so his piece in Re:Working Labor was dedicated to one of his teachers. Harun Farocki passed away in 2015, but we knew about the project “Labour in a Single Shot” with Antje Ehmann and Eva Stotz. We knew there was an educational and discursive component to the project, so it was an excellent fit for SAIC. They were excited because we have editing equipment, a screening room, and people who could TA and facilitate.

ER As for institutional relationships, I think that both of us have been in a number of challenging situations in relations to institutions and in confronting what the reality is for artists within institutions. Basically, unless you’re a blue chip artist, where you can command a price in relation to your market value, for the most part having the opportunity [to exhibit] is considered enough. And never mind getting paid for your labor, artists also often assume the cost of production. So we were very sensitive not to put that kind of burden on anyone, but to use the fellowship funding as a resource for supporting work and supporting people.

DE Everyone also had a say in what they should get paid for their participation in Re:Working Labor because they proposed it. I think as a model, what W.A.G.E. does is demystify and create an information base, which is important because power is all about mystification. What you don’t know empowers the other person, and that’s true in every labor situation. I think oftentimes, at our school, that comes up because you don’t know enough information, and so the opacity of the situation is leveraged against you in different ways. On the other hand, every labor situation I’ve ever been in has demanded of me personally to set my own limits, and to set my own parameters with engagement.

ER That’s also a way of getting a good deal institutionally, because people are always undervaluing themselves.

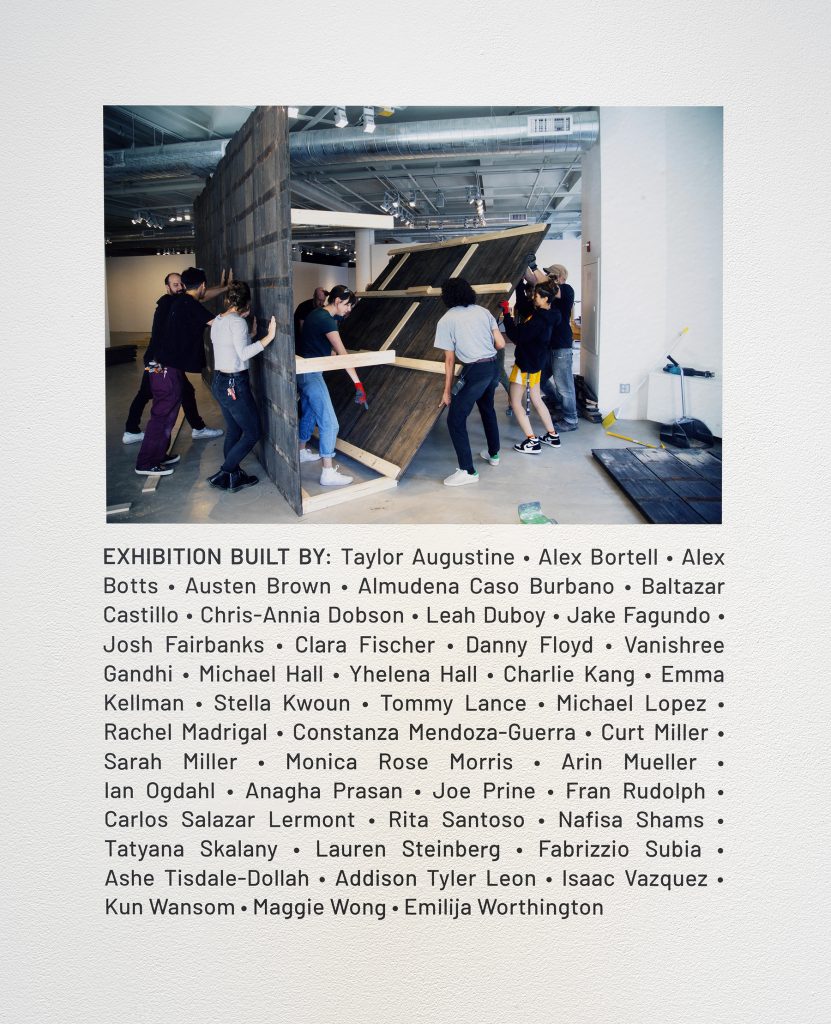

Leah Gallant: A wall text in the show lists everyone involved with the work of putting it together, from art handlers to curators, with no hierarchy of importance. How did you go about trying to ensure the process of curating the show was equitable for all involved? What challenges did you face in doing so?

ER It’s a response to the way in which it’s usually the sponsors who get the name recognition at the door. The labor of all the people whose talent, skills and dedication are evident in the exhibition itself is usually invisibilized.

DE That was a very conscious choice. We decided not to put logos out in the front, not to brand things, just to have a statement. We had to have the names of these funders, but it’s very low-key. To include the image and names of everyone involved with working on the exhibition in a non-hierarchical way, located in the center of the show, you have no idea how important that was to them. They really responded to it.

ER Because they never get that credit. They built that piece for Ibrahim [Mahatma], and the show looked very tight. The level of production was extremely high, and it was thanks to an extraordinary gallery staff with a lot of experience, talent, and skill. And many student workers were also makers, so they were also engaged. The Sullivan Galleries is a real lab for learning.

DE We depended on them, and we were also really thankful, we still are. A project of this scale is always a process in which a kind of ethos of either hierarchy or community gets built, and we always chose community.

Leah Gallant: On the subject of corporate sponsorship, it seems like we’re at a possible juncture or point of pressure, which I think has to do with the dual political quality of the art world. My sense is that artists and cultural workers are overwhelmingly progressive — in a recent survey of working art critics by Mary Louise Schumacher, for example, 85% said that they voted Democratic. But the sources of funding in the art world — collectors, donors, and board members at cultural institutions — may have made their fortunes in industries related to exploitation and violence. Some recent controversies have included the Sackler family’s ties to the opium epidemic and now-former Whitney Museum vice chair Warren Kanders’ ties to the company that manufactures tear gas used on the U.S.-Mexico border. Closer to home, the current edition of the Chicago Architecture Biennial, which centers work about decolonization and social justice, is sponsored by BP. Does art about the climate crisis cancel itself out if it’s funded by BP? And who is this work for, if the audiences of contemporary art are already overwhelmingly progressive? Who is the audience for Re:Working Labor?

DE You are. I’m serious, I was absolutely laser focused on the students. To me, it was a pedagogical tool. I wanted more students to be aware that this is their issue they have to deal with, socially and politically, but also personally. Instead of going down the expected paths put in front of them about personal entrepreneurship and branding, producing one’s own individuality in the world, what we were trying to model are different forms of collectivity or collaborative presence in the world.

ER We were also thinking about different ways of working, how things didn’t need to be authored by an individual, and how the richness of the show depended on this kind of collectivity and interdisciplinarity and more international perspectives. To have somebody who just graduated from graduate school and Mierle Laderman Ukeles in the same show, it produced something very different that countered the expected hierarchical career path.

DE It also has to do with commodification of the artwork and the artist, and the way in which art has become an investment tool or investment vehicle. So much art that’s bought is never even exhibited, it goes into these customs houses that sit in bonded warehouses. People don’t even look at the work until it gets sold the next time around. It’s basically in a vault. Who’s interested in being part of that?

DE We took Michael Rakowitz through the show. I was taking him with a class and I was pointing to Gregory Sholette’s piece, a plaque depicting the last organizing meeting of the Gulf Labor Coalition, which called for a boycott of the recently announced Guggenheim Abu Dhabi for its treatment of migrant workers. I said to my class, “Michael was the first artist in the Whitney Biennial to withdraw his work from it,” and he said, “I was part of Gulf Labor, and I learned everything from them.” Consciousness has a way of multiplying. What I think is that people respond in their own way, but the consciousness produces a different relation to one’s own practice and to the interface of the world.

ER It’s a good question, it’s not something that can be ignored. It needs to be confronted, but there isn’t only one way of doing it. There are lots of ways.

DE We also came up at a different moment, when there were many more alternative structures for being an artist.

ER And it wasn’t so expensive. Living was a lot cheaper. You could work part-time and then stop working for a while. All the development in the Boston area, where we used to live, and also in New York and many other cities, produces a climate where people can barely keep their heads above water, never mind having time for creative work.

DE This allure that you’re going to be a viable artist in that world, it’s only possible for one or two thousand people. It’s infinitely small in relation to how many people make work. In the end, we have to define for ourselves what we see as the role of culture and cultural production. Is it a commodity, is it to be valorized in a museum setting, or is it to be integrated into communities of various kinds? Is it an agent of conversation, intellectual interplay, and political change?

Leah Gallant: In Stephanie Rothenberg’s “Proof of Soil,” bacteria feeding off the materials that have accumulated in the soil from pollution produce electricity to maintain a cryptocurrency network. I love this piece because it’s funny and poignant. Can you tell me more about this piece? Is this actually an applicable model to offsetting the carbon footprint of cryptocurrency networks? What role do you think humor should play in political art, or activism more broadly?

ER I think about what art can do that other forms can’t do. In that piece, the role of humor is very subversive. In modeling these complex systems in a way that brings them into conversation together, it becomes a form that you kind of begin to understand. All of those things are the strength of Rothenberg’s work, as well as the way she’s modeling complex systems, not from the perspective of a scientist or an economist, but from the perspective of an artist. The sculpture was producing energy and capital, but at the same time, you’re looking at a sandbox full of weeds, a facsimile of electrical charge, and this diagram of brown fields. We’re struggling with all of these issues in the real world, and she’s fearless in how she confronts them in her work.

Leah Gallant: Did you come across new paradigms for approaching social change through the process of working on this project? Did it change your own perspectives on what labor is and how to build a more equitable world?

ER I think the project was an affirmation, in a lot of ways, of the possibility of producing something that we ourselves could not produce on our own. That collective and collaborative aspect of it really became the backbone of the project. We also want to credit the school for supporting us. It speaks to the necessity of more long-term projects that offer a chance for things to develop and grow into something that’s substantial, that counters acceleration and quick fixes and produces deeper relations.

DE After Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ piece “Serving IV: “As Long As We Are Here…,”” in which SAIC maintenance staff members were invited to eat a lunch served by SAIC students, everybody left that room feeling high. It was incredible. You see people who you saw at that event, and you say hello to each other because that connection was made.

ER Yes, even though we knew her work, and we were participants in the planning and the execution of it, it was a very, very, powerful event. It has carried over, and it creates another opening in a very hierarchical institution which divides groups of people, just by bringing people together for that lunch.

DE It was very cool, but also very modest. You have to keep your frame well calibrated. It’s not going to change the world, but if it changes a few people, that’s great.