Illustration by Yajurvi Haritwal

I cried every g–d— episode.

Granted, I binged the Netflix series “Heartstopper” as I struggled through COVID-19, but my intense emotional reaction had me wondering: “Dude, why am I trippin’?” Feel-good ugly cries are not a known symptom of COVID-19, so surely something else had me in my feels. The plot in no way mirrored my coming out as a gay man from the Deep South, and, as far as I know, neither did it mirror that of a single one of my Gen X friends.

And yet.

YET… The modern-day, teenage, coming-of-age story set in the U.K., based on the graphic novel series by Alice Oseman, still resonated deeply with this Gen Xer.

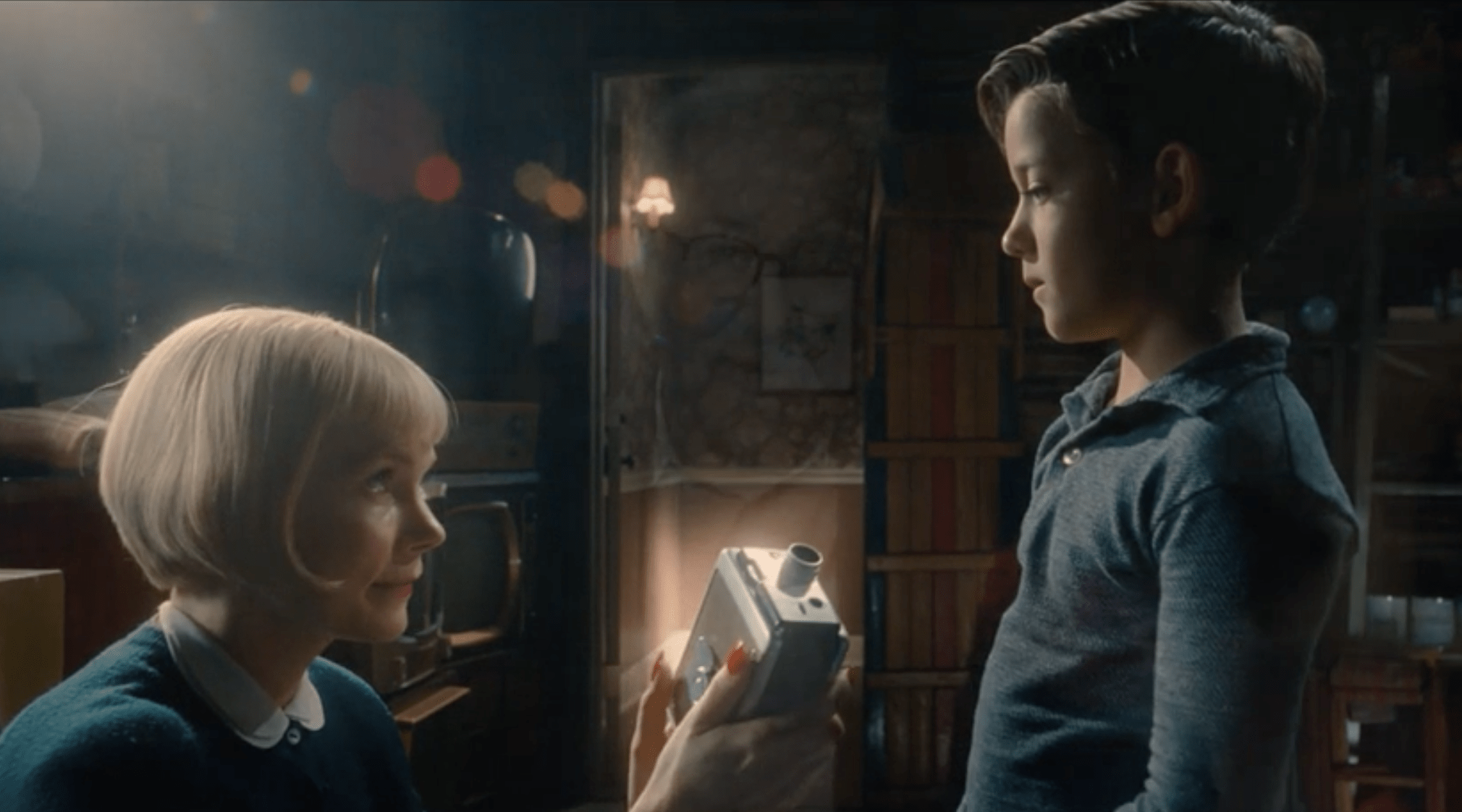

Every emotion I’d ever ignored crawled forth as I howled, gasped, laughed, and sobbed. I held tight to an old teddy bear as I oscillated with identification between the two main characters, high school students at Truham Grammar School. In one moment, I landed squarely with Charlie Spring (played by Joe Locke): the teased nerd, different from most everyone else, and experiencing that gut-wrenching crush. In the next, I related with Nick Nelson (played by Kit Connor) when he turns to Google on the internet and realizes how “am I gay?” can be incredibly complex and isn’t always the right question.

Even decades after my own experience growing up in a small, Mississippi college town in the ‘80s, I’m learning more about who I am and how labels can be entirely arbitrary and misguided. Pre-“Will & Grace,” pre-Ellen’s coming out, queer characters (if they appeared) at that time often felt theatrical and camp (“The Rocky Horror Picture Show”) or covert and stereotyped (Jo from “Facts of Life”). Systematic homophobia was fueled by a lack of understanding (“homosexuality” had only recently been removed from the DSM as a diagnosis in 1973 and would not be removed from the International Classification of Diseases by the World Health Organization until 1990), spiteful religious dogma, reckless and intentional disregard for a plague that decimated the gay male population, and a baseline aversion to anything “different.” Conversational references to anyone openly gay were qualified with “well, you know, he’s different” as if the word “different” somehow excused not only the “behavior” but also any acquaintanceship. At the time, I didn’t know anyone who was out. Right as southern Christianity made me slowly hate myself, my own internal homophobia came to light for a time.

My own denial was so powerful that I didn’t know I lived in a Mississippi closet until I was thirty years old and had left the state.

Although a number of comedians have apologized for derogatory jokes from that era, I still remember the bits about AIDS and gay sex. I especially remember the homophobic fraternity brother in college who engaged in his own personal, weird witch hunt for anyone he suspected as gay. He once admitted to fabricating lies to force guys out of the fraternity and even resorted to scouring yearbooks to see who had joined which clubs and might, therefore, be gay. Someone definitely spent way too much time obsessing about other folks’ closets.

My own coming-of-age/coming out story is a drunken, misshapen, misdirected detour. I drowned my inner voice with booze. I ran away by staying in place, giving up a fantastic scholarship at a first-rate university. I conformed to the status quo by attending a university where I could coast and where I would endeavor to “fit in” despite knowing better. I didn’t question anything critical, whether it was race, gender, orientation, classism … not anything lest it crack the wall I’d created. By the time I started to accept myself, my detour had become the long way around. Yet, perhaps, that dark calculus is exactly what I needed to experience before I could head to Chicago for an MFA program as a 48-year-old sober queer.

There are parallels from ‘80s zealous homophobia to today’s pearl-clutching politicians who stoke fires of hate in the name of “family.” When mayors like Gene McGee attempt to withhold library funds over LGBTQ+ books in direct violation of basic First Amendment rights, when Florida legislators prohibit educators from talking with young students about LGBTQ+ lived experiences, and when politicians want to outlaw critical thinking in schools on issues like race, “Heartstopper” nonetheless overwhelmed me with gratitude.

That is why “Heartstopper” wrecked me in the best possible way: it’s the coming out journey I never lived. It’s Mr. Ajayi (played by Fisayo Akinade): The high school teacher confidant I never had. It’s the annoying yet endearing sister Tori Spring (played by Jenny Walser) who goes to bat for her pesky brother. It’s the teenage crush-turned-romance. It’s the boyfriend I want to have and the boyfriend I want to be. It’s the beat drop to Chvrches’ “Clearest Blue” on the dance floor in the third episode when one thing is instantly clear to Nick: Everything. Will. Be. Alright. Those collective moments unfolded like an unexpected current that pushed me down the shoreline, toward a sunnier, friendlier beach I didn’t know existed and didn’t realize I’d always wanted.

The series showed that my coming out story doesn’t have to be — and isn’t — repeated. In its differences, it also reminded me of my own beautiful moments. As I watched *that* conversation between Nick and his mother Sarah (played by Olivia Colman, who reportedly couldn’t stop crying during rehearsal of the scene), I remembered when my mom eventually embraced me and tried–albeit awkwardly and endearingly–to set me up with a former student of hers. Like Charlie, I had friends who never wavered. Not once. Pastors and teachers and coworkers and neighbors are more interested in my character, and the question of who I love is no more a concern than whether I like vanilla or chocolate or strawberry ice cream.

In a world of swiping left and right on apps, maybe we haven’t fully lost the magic of getting to know someone with the stunningly beautiful awkwardness of body language and code switching and internal debates and uncertainties: Do they like me? Do they want to know me? It’s the fundamental notion: am I worthy, as I am?

The answer is YES. Always YES. A resounding YES.

Ultimately, “Heartstopper” reveals a hopeful present for Nick and Charlie (and the rest of us) that allows the unabashed exploration of inner innocence and each person’s desire to find their place in the universe. There’s radical freedom in believing that, no matter how a politician describes us, or we might view ourselves, we are loved. Someone will love us for who we are. WE can love someone for who THEY are. Someone will dash in panic through a downpour to stand at a doorway merely to utter: “Hi.” Or, that we can be that person, running through a storm without a coat, to stand on a doorstep, drenched in cold rain, and make everything alright for someone we adore without hesitation.

John W. Bateman has a secret addiction to glitter and, contrary to his southern roots, does NOT like sweet tea. He recently left his southern unicorn lumberjack shack and moved to Chicago to pursue an MFA in writing at SAIC.

This is a beautiful piece. I’m also a Gen Xer who’s a bit obsessed with Heartstopper and all the feelings it ignited and resurfaced. It’s a beautiful, hopeful, piece – well-acted, directed, and written. The emotional connections are amazing and definitely something to strive for no matter our age.