Knock knock. A hand reaches out of your phone screen, and slaps you in the face. Being canceled on the Internet can feel like that, and so much more. Many act like what happens on the Internet can hold no real consequences… until they do.

As COVID-19 hit in 2020, human activities came to a pause on a global scale. Just before nationwide quarantine in China began in March 2020, the 227 Incident caught Chinese web users’ attention at the same time.

On 24 Feb. 2020, a quiet battle helmed by a group of fans against the fanfiction “Xia Zhui” (“Falling”) began on Weibo, a Chinese social media platform with more than 445 million monthly active users by 2018. “Xia Zhui” fell into the category of fanfiction known as RPF — Real People Fanfiction, or essentially, fanfiction written about real celebrities like actors and musicians, rather than fictional characters — and revolved around actor and former idol Xiao Zhan. Xiao is notable for starring in “The Untamed,” a TV series adapted from a boys’ love romance novel.

As the show grew popular among Asian audiences, passing 9.5 billion views on the streaming platform Tencent Video in June 2021, fans began to publish RPF about Xiao on popular fanfiction website Archive Of Our Own (AO3). Fans were unhappy with “Xia Zhui” and other RPF that feminized Xiao Zhan, and fans began sabotaging and attempting to censor fanfiction platforms in their entirety, in defense of his reputation. Led and planned by a group of big fans, they declared a “media war”on 27 February: platforms like AO3 and Lofter were reported and rated as vulgar; fanfiction writers and video-makers received waves of verbal abuse. This aggressive attack on fan culture also expanded to other ACG (Anime, Comic, and Games) cultures. The date, Feb. 27, thus dubbed this the “227 Incident.”

On 29 Feb. 2020, AO3 was suspended and became inaccessible to Chinese mainland users, along with other recreational works containing “sensitive content.” People who were originally indifferent to the chaos on Weibo started to pay attention as the large ACG population felt offended and enraged.

In March, fights among fans led to widespread denouncement of Xiao Zhan himself, as his team failed to respond to the ongoing turmoil led by his fans. In April, he posted an apology letter on Weibo which nonetheless gained even more backlash from his haters who soon began to include regular web users. Within a month, tags like #BoycottingXiaoZhan’sAdvertisements and #BoycottingXiaoZhan’sShows flourished on Weibo. Countless personal insults filled the screen of his TV series and fan-made videos on streaming platforms like Tencent Video and Bilibili. Commercial brands erased him from their advertisements and dropped him as brand ambassador. It was a wildfire that burned through social media and eventually converged on him.

In October 2020, after six months of vanishing from the public eye, he was invited as a guest singer to a show. On the guest list, he was named as an anonymous singer to prevent any backlash before the show’s release. For the next six months, though invited as the guest singer to multiple shows, no official message of his presence was announced until his performing moments. His itinerary was confidential and no TV series that feature him streamed in any platforms prior to July 2021.

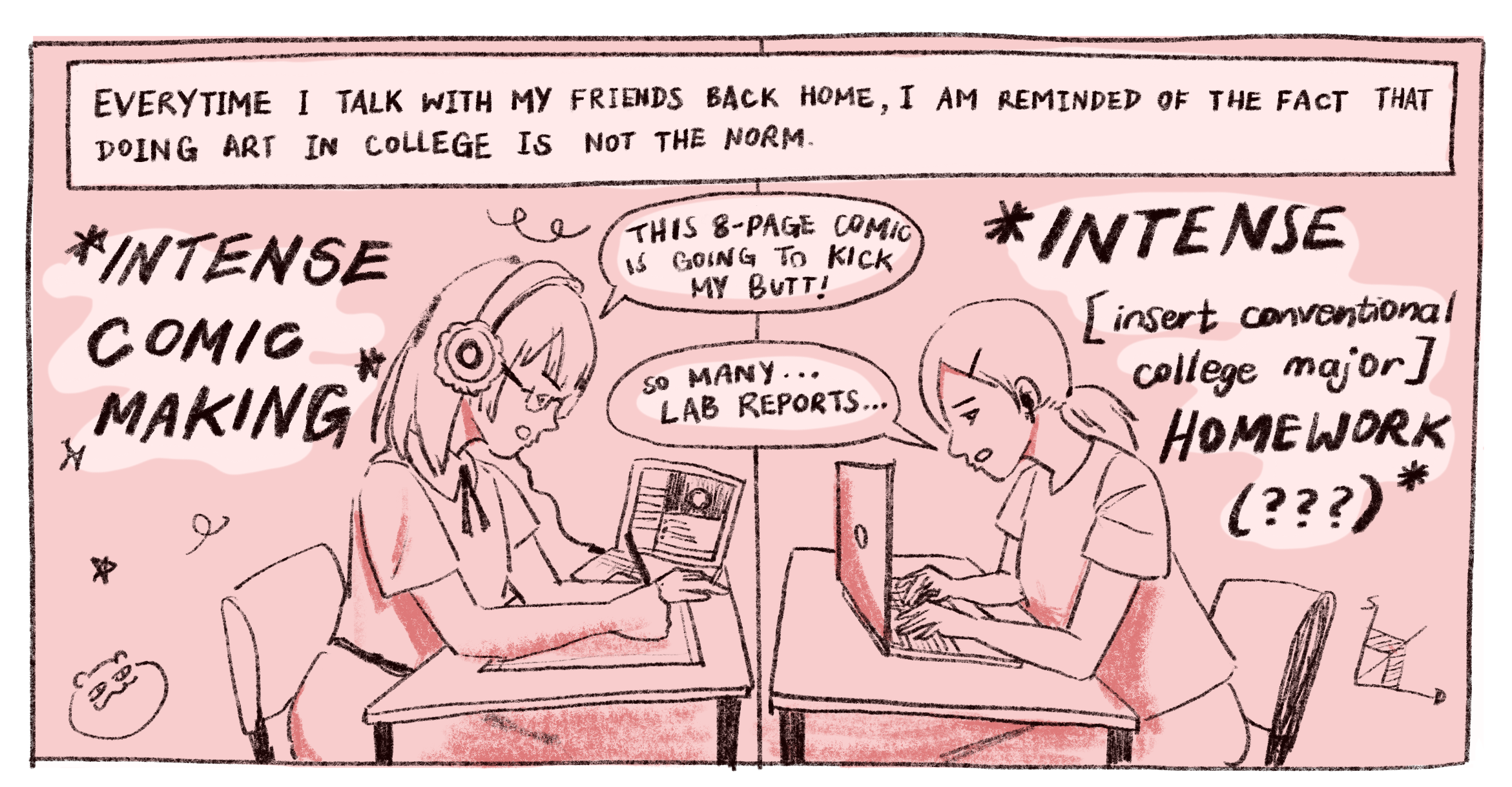

In the 227 Incident’s aftermath, people still debate about the extent a public figure is responsible for his supporters. Is silence acknowledgement or disapproval of one’s fans and their actions? Since people become one’s fans voluntarily, without the figure’s approval, are they just representing their fan community, or the individual too? The 227 Incident was a virtual war that came out of bias and rested on bias; a selfish demand for the erasure of others’ creative work that evolved into blind aggression which ended up destroying the figure they initially sought to protect. Victims become bullies, and vice versa. It’s almost comical.

While discussion of cancel culture centers mostly on discussions of morality and responsibility, we forget that social media culture itself enables such unjust “cancellations” to continue. When “free speech” on the Internet runs amok, it is the oversaturation of information that wins the popular opinion, not ethics and laws. Oversaturating a platform with messages is employed as a weapon to cancel out a minority’s voice. This influx of information also leaves people with the impression that the Internet has no memory, encouraging people to either carelessly add intense emotions to their expressions, or defend their stance by bombarding innocents to clear ground for their own points of view. Moreover, anonymity and the ease of clicking a few buttons to share your truth with the world often give people too much confidence in their stubborn beliefs. We forget about others’ existence as we deny their emotional responses to rolling information. In attempting to conquer the Internet for ourselves, we become nothing short of fanatical.

In the case of the 227 Incident, we can see that oftentimes, cancellation is never about the others but the self. It is not about ethics — rather, about reinforcing one’s opinion through unfeeling, predatory methods.