Public art shapes and is shaped by worldviews of what is considered important and good. It is an exercise in public memory and cultural value. As ideas shift about what is right — or as control of public space is taken by violent or nonviolent means — our built environment changes. Monuments get put up and torn down. What becomes visible in these moments of conversion or destruction is who believes what is important, and who has the power and money to decide.

Nowhere is this more confounding than in the controversy surrounding a cycle of WPA murals depicting the life of George Washington at the George Washington High School in San Francisco. In this case, unlike the sides that formed around the Charlottesville monument, those supporting its destruction and those opposing it are people of color, members of the high school community, leftists and liberals.

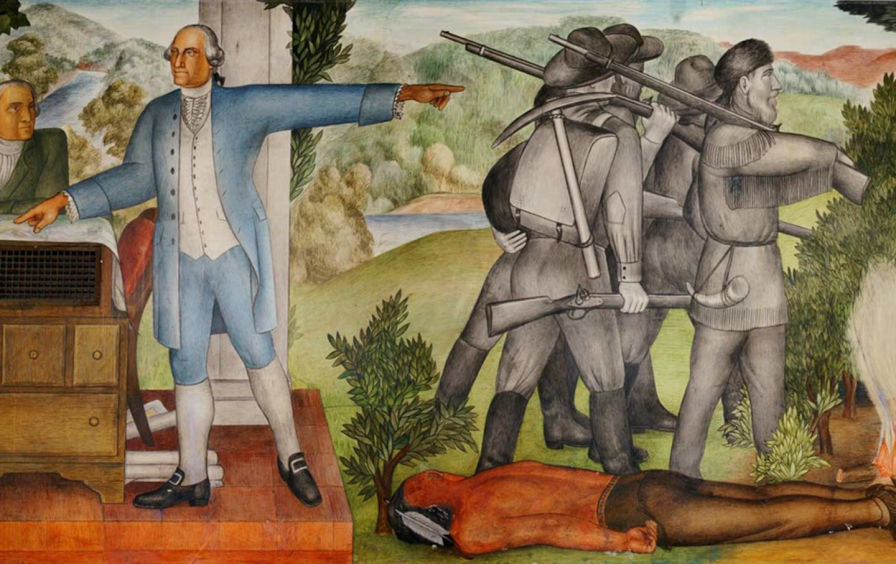

“The Life of George Washington” is a cycle of 13 murals by Russian émigré artist Victor Arnautoff, painted in 1935 – 1936. In the murals, scenes from the life of the first president are shown in bright, swarthy figures with modeled shading, testament to the communist painter’s time studying with Diego Rivera. The debate centers around two panels in particular. In one, slaves are pictured in the background, working on George Washington’s family plantation, Mount Vernon. In another, a dead Native American man is shown lying at the feet of a four gun-toting settlers who walk over him en route to Westward expansion.

In the spring of 2019, a committee of high school parents and community members assembled to investigate the murals found that they constituted a threatening environment for black and Native students, and demanded their removal. In June 2019, after months of contentious meetings and op-eds, the San Francisco Board of Education voted unanimously to whitewash the murals. Two months later, they re-voted instead 4-3 to cover the panels with a temporary veneer — a compromise which seemed to please no one. But the debate continues: in early October of this year, the George Washington High School Alumni Association announced it was suing the School Board over its decision to cover the murals without first undergoing an environmental review, required by California state law.

This wasn’t the first time the murals have come under fire. In the 1960s, black students at the high school criticized the mural for its depiction of black Americans. They called for the addition of a mural that centered the experiences and contributions of black americans. As Robin D.G. Kelley, writing in The Nation, points out, the criticism was focused on the depictions of slaves, with no mention of the dead Native American. Eventually, then-22 year old black artist Dewey Crumpler completed a mural, entitled “Multi-Ethnic Heritage,” that celebrates the histories of Americans of color. Located in the same hallway as the Washington murals, through a set of doors, Crumpler’s image shows a Native American figure holding Alcatraz as Turtle Island, as well as Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez.

Those who support the destruction of the Washington murals point to the fact that the violence against black and Native American subjects is an unwelcome visual assault inflicted on viewers of color. As one parent said, “Not one Native American student should feel uncomfortable at having to confront this image every day.” (Students apparently use parts of the mural as convenient labels for meeting points, agreeing, for example, to meet “at the dead Indian.”) Those who support the mural’s preservation note Arnautoff’s critical handling of American history: he dared to show the raced violence the United States was founded upon, they say, and what is needed is education about Native genocide and white supremacy as this specific mural refers to it, as well as in American history curriculums at large.

I am a white viewer, and I believe that centering the perspectives of people of color matters more than my own reaction. But there is no clear division along racial lines between the two sides. Some of the most prominent supporters of its destruction are black and Native American students and parents; an open letter drafted by some of them was signed by the San Francisco chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), the Chinese Progressive Association, and San Francisco Rising, an organization that builds political power in communities of color.

“Preservationists,” on the other hand, include Choctaw Indian elder Tamaka Bailey; Dread Scott, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago alumni whose 1988 work involving the American flag was denounced by Congress; and muralist Dewey Crumpler, who has said that to destroy the George Washington murals would be to destroy his own work. (Many scholars and arts professionals, such as Judith Butler, Michael Fried, and New York Times co-chief art critic Roberta Smith, have also opposed its destruction.) It’s not Neo-Nazi vs. Antifa, but liberal vs. liberal. And on both sides, there are very vocal white people claiming to represent the interests of people of color.

Part of the ambiguity is in the visual. The very same elements are cited as visual evidence by each side to support their argument. The slaves bent over in the fields in the background either show the representation of black Americans as docile, passive recipients of violence; or they show honestly the raced violence on which this country is built: on the stolen labor and livelihood of black people. As Robert W. Cherney, a historian who wrote a biography on Arnautoff, has pointed out, this ambiguity was necessary in order for the artist to evade censorship in his own time: it had to be able to pass as Americana to sidestep the fate of, say, Diego Rivera’s mural at the Rockefeller Center.

I asked Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, indigenous historian and author of “An Indigenous People’s History of the United States,” who tweeted her support for the mural’s preservation, why she thought this issue, unlike other recent controversies around art that relate to the United State’s foundations in raced violence, has pitted progressives, leftists, and community members of color against one another. She told me by email:

“Because this is the first encounter between Native Americans and liberals. Native activists have for decades protested anti-Indigenous public works and figures, notably, for instance, Columbus and Junipero Serra (the Franciscan/Spanish colonizer of California Natives) statuary and hero worship. In the Washington mural, what most eyes perceived was the trope of the dead Indian, the erasure of Native people. They were looking at the effect rather than the intent of the artist. Liberals are all to happy to admit to European and United States colonial genocide but less willing to deal with the ongoing presence and colonization of Native peoples. Local and national art professionals and preservations did not help matters with their arguments that all art is beyond reproach, romanticizing art as such, pointing out that art should be provocative, but their arguments were specious and without any attempts to comprehend the trauma of colonialism that is not just historical, but woven into U.S. culture.”

What has been glossed as a two-option problem actually holds far greater nuances. As Dunbar-Ortiz, Scott and Crumpler have pointed out, the knee jerk response of many white pro-preservation commentators has been to cry censorship without acknowledging that this mural is a source of pain. As Crumpler says in an Artnet interview with Ben Davis, “I am right with those students. I support their activism. It is just that the outcome here is confused.”

The controversy over these murals implies something else. It is that there has been a moral shift in how we think about representation, in which only people who are part of a minority group should have the right to represent their experience.

But Arnautoff wasn’t working in the age of Tumblr politics. He was an artist and a communist at a time when censorship of anything deemed anti-American posed a real threat to radicals like himself. It was a threat Arnautoff faced when he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) for defending the work of his fellow artist, Anton Refregier, whose San Francisco post office murals came under attack for depicting the Chinese-Americans who built the railroad being assaulted by a racist mob.

When I asked Dunbar-Ortiz what she thought should be done about the mural, she told me, “The four panels of the fresco tell an accurate history and should be used as a teaching tool along with materials and speakers who stress the resistance and continued existence of Native peoples.”

I support the preservation and continued display of the murals, a position that I would not hold if it were not for the critical perspectives of artists and scholars of color. But only on the condition that those spurred to action on behalf of some pictures will campaign even harder to build material and political power for Native and black members of the high school community and in the country at large. I must hold myself to this as well. If those who support the mural’s preservation, particularly those white people who support it, cannot stand with black and Native communities in building equity, then the mural will become a testament to selective democracy, American-style: the type of democracy whose values of freedom of speech and artistic expression are built on stolen lives and stolen land.

Hi. Thanks for this interesting essay. As an FYI, Dunbar-Ortiz’s status as “indigenous” is contested: https://www.facebook.com/notes/hank-adams/the-white-real-roots-of-roxanne-dunbar-ortiz/10153001046118263/