Before this summer, I knew exactly two things about Joan Flasch: I knew she had a special book collection named after her at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), and I knew she had the coolest name ever. I mean, come on: ”Joan Flasch” sounds like the name of a superhero.

Then an incredible coincidence occurred.

In Knoxville, Tennessee, on assignment for a totally non-SAIC-related project, I met a woman named Merikay Waldvogel, a curator and author who specializes in American quilt history. Over the course of our conversation, I told Waldvogel I was pursuing my MFA in Writing here at SAIC.

“Oh, does the name ‘Joan Flasch’ ring a bell?” Waldvogel asked. I said that yes, it certainly did. Why?

“Joan was a dear friend of mine,” said Waldvogel. “We lived together in Chicago.”

I nearly dropped my iced tea.

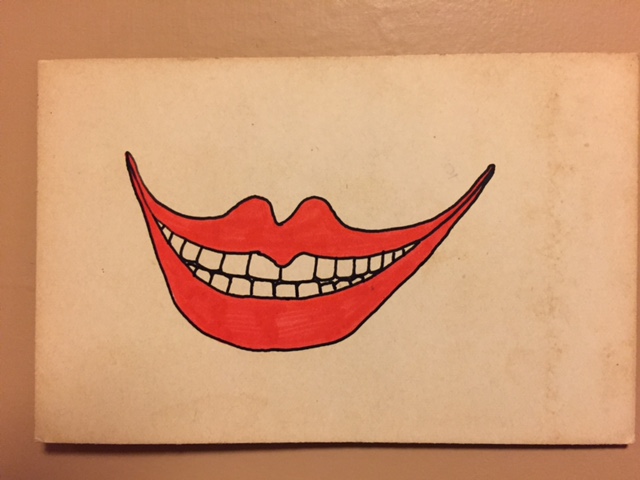

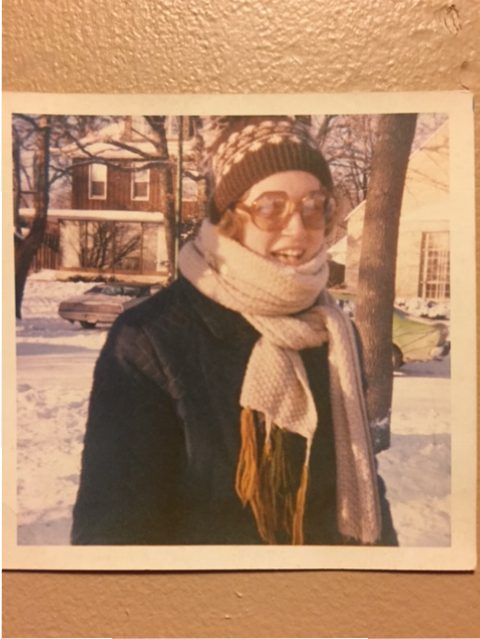

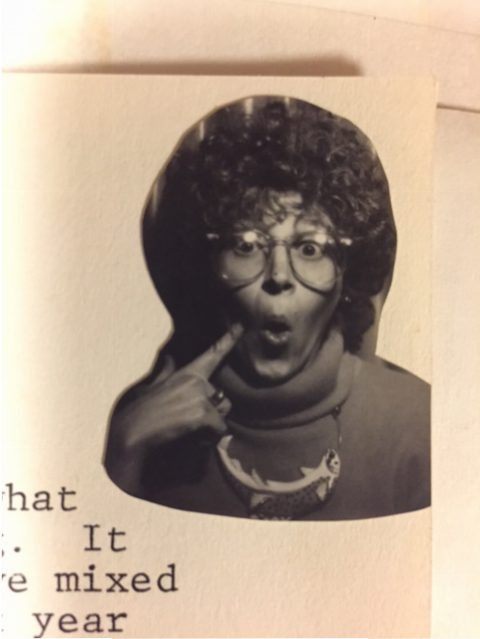

As Waldvogel told me stories about Flasch and showed me dozens of letters, postcards, and artwork she had received from her friend over the years — all of it in Flasch’s warm, whip-smart style — that magnetic woman began to come into focus for me. The more I learned about her, the more obsessed I became with finding out more about Joan Flasch and her brief but absolutely superheroic time on the planet.

‘It Was a Heady Time’

Joan Eileen Flasch was born in 1949 in Chicago, the second-oldest of four kids. Young Joan showed an early affinity and aptitude for art.

“She’d finish all my art projects for me,” said Betty Flasch, Joan’s younger sister by 18 months. “I remember I had to make a hooked rug at one point. It was a total disaster, so Joan fixed it for me.”

SAIC has long offered summer youth programming, and back when Joan was in middle school, summer art at SAIC was called the Young Artist Studio. Just a quick trip south from their home on the northwest side of Chicago, Flasch’s parents enrolled their daughter in the program, which she adored. Flasch spent her junior high and high school summers immersed in art right here at SAIC, and that time laid the foundation of her lifelong connection to the institution.

The art skills she was learning were put to good use: Betty Flasch remembered a particularly ambitious work her sister created in high school.

“We were both members of Future Teachers of America,” Betty told me. “There was a bake sale, and Joan was learning about the Fibonacci Sequence in math class, apparently, so she made cakes with multi-colored frosting that spelled out F-I-B-O-N-A-C-C-I.” Betty remembered the cakes selling out.

After graduating from Foreman High in 1967, Flasch applied and was accepted, not surprisingly, to SAIC. Four years later, she graduated with a BFA in Photography and began looking for a summer job. That’s where Waldvogel comes in.

The two graduated around the same time, and though Waldvogel had been at the University of Michigan, she had a connection to SAIC: She knew Marni Sweet, good friend to Judy Helder, SAIC’s Dean of Admissions at the time. Sweet was involved with the Girl Scouts of America and was tasked with staffing a camp in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, that summer. Sweet convinced Waldvogel to come be a counselor.

Judy Helder was helping out with recruiting efforts over at SAIC, too.

“Judy offered jobs to some of her students and Joan was one of them,” Waldvogel said. “She actually gave Joan the position of Arts & Crafts Director. Suddenly, there was a huge group of SAIC students running this Girl Scout camp in Elkhorn. Betty got a job there, too. It was great.”

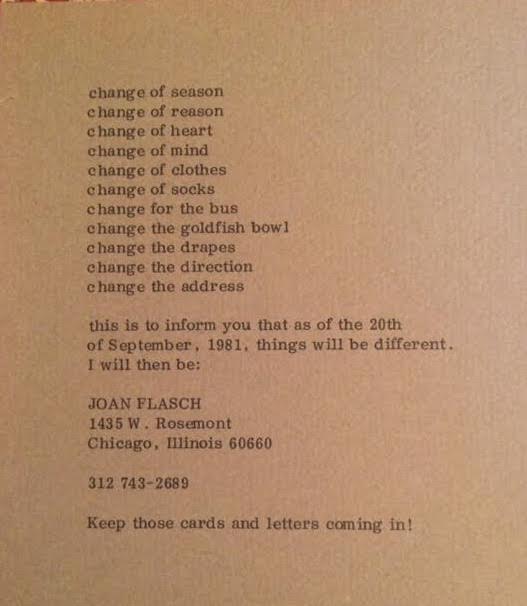

Waldvogel and the Flasch girls bonded that summer (campfire songs and craft glue will do it every time), and after the Girl Scouts went home for the summer, Merikay and Joan decided to get a place in the city.

“We got an apartment on Surf Street and Broadway in this big old building with high ceilings,” Waldvogel said. “It really became the go-to place. Everyone would come hang out there. It was a wonderful neighborhood, all these little shops and restaurants. The original Barbara’s Bookstore was right around the corner. It was a heady time.”

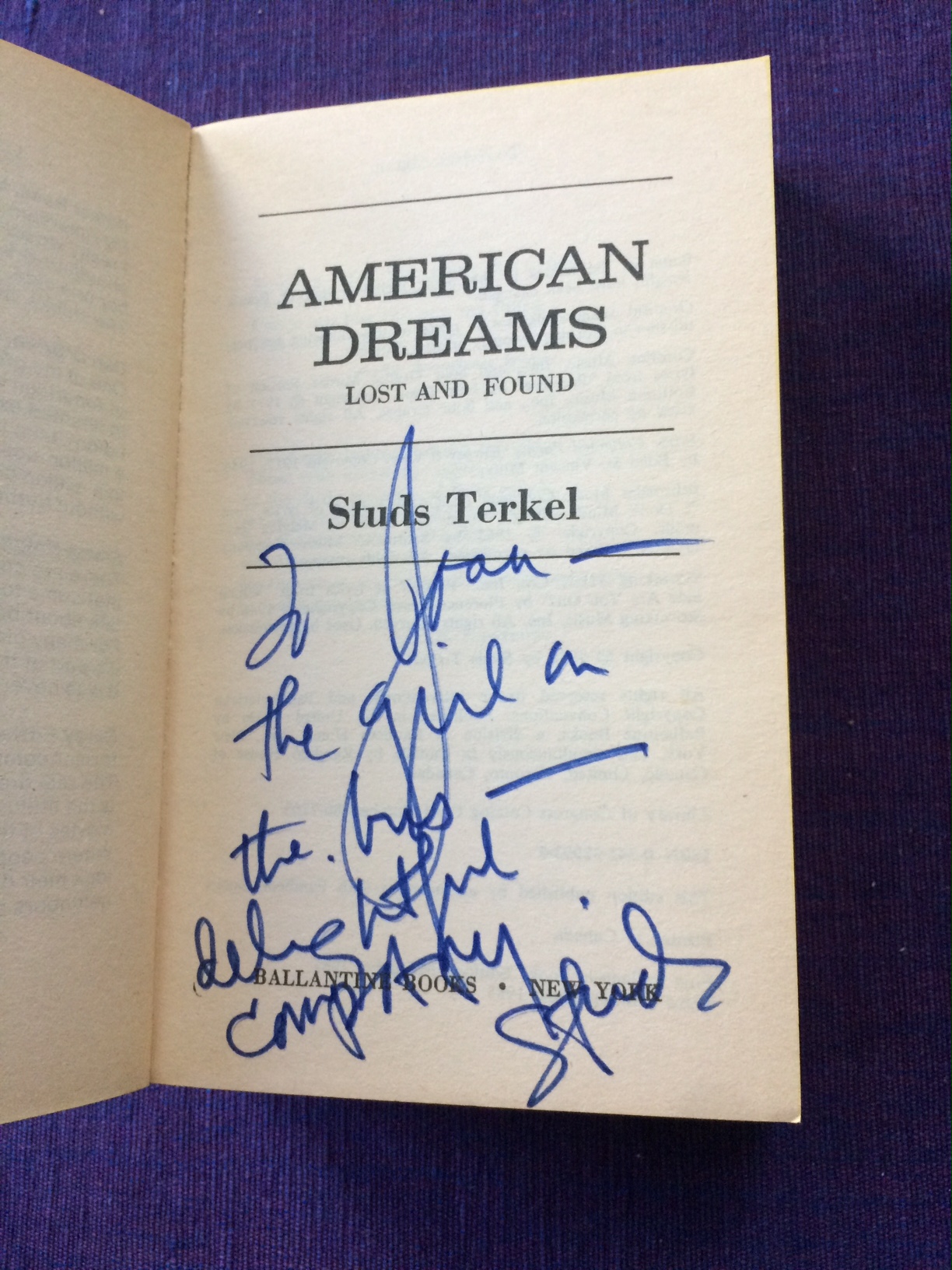

The life the girls and their friends led might also be described as “you-gotta-be-kidding-me” fabulous: The circles Flasch and Waldvogel ran in paint a picture of a specific moment in the early 1970s that make a Chicago history nerd like me drool. The girls rubbed elbows with the early Chicago Reader crew; they got drinks with Roger Ebert at the legendary journalist-watering hole, O’Rourke’s; they were on a first-name basis with writer Leonard Pitts, and they had a rather famous neighbor: Studs Terkel lived just around the corner.

“Studs and Joan got along really well,” said Waldvogel, almost off-handedly. No kidding: Joan and Studs often sat together as they rode the Clark 22 bus downtown, Studs off to do his Studs thing and Joan on her way to campus.

Because in 1972, Flasch returned to her beloved SAIC, this time as an employee. In typical Joan Flash fashion, her position was one of a kind: As manager of SAIC’s Student Store, Flasch would be less a staffer, more a kind of nucleus for the whole blinkin’ place.

Paper, Paper Everywhere

To understand the contributions Joan Flasch made to SAIC as manager of the Student Store, you have to first understand how different this school was 50 years ago.

There have always been sensitive painters and professors wearing complicated eyeglasses, of course, and SAIC is and has always been committed to offering world-class instruction in the arts. But consider that in the 70s, the internet was still 20 years away. The school didn’t offer degrees in Writing, Architecture, or Arts Administration, among others. If you said the words “new media” to someone, they’d probably figure you were talking about the morning newspaper. The student population was less than a third what it is today and was made up mostly of graduate students and the entire campus was tucked under the east wing of the museum.

And before everyone had to trudge over to Dick Blick through the ice and snow for pasteboards and brushes, they could just head down to the Student Store for all their textbook and art supply needs. Sort of.

Located in the bowels of the Columbus Drive building, everyone I talked to about the old Student Store used words like “bizarre” and “disaster” and “chaotic nightmare.”

That was before Joan, though.

“Joan was by far the most organized person I had ever met,” Waldvogel told me, “and she was so good with time management. She was the one who got the Store under control.”

Flasch cleaned. She reorganized. She tidied. But more than that, she cared about her staff and took extremely seriously the task of stocking supplies for SAIC students and faculty. This was crucial.

Sally Alatalo, chair of the MFA Writing Department, was a student of Flasch’s in the 1980s — we’ll get to Joan’s teaching in a minute — and remembers how Flasch approached her job as Student Store manager.

“Joan loved materials,” said Alatalo. “Everything in that store — metals, sculpting materials, fiber materials — it was all explicitly researched. Yes, faculty requested specific materials for certain classes, but beyond that, Joan investigated everything she stocked. She was invested in recognizing the stability, the archivability, the archive goals of any given material. This was not a corporate giant dictating what would sell; it was all coming from Joan.”

Her personal touch and 360-view made all the difference. Flasch wrote all the product labels by hand, for example. When it came to papers, she personally pH tested every last one.

For 13 years, Flasch kept the entire shop under control, which is not to say she ran the place with an iron fist; hers was more of a velvet hammer approach, and the students loved her for it. Practically every student and faculty member came through the Store at some point, and thus encountered (and crushed on) Joan Flasch. What wasn’t to like? She was professional, warm, and truly hilarious, with a sense of humor that might be described as “intelligent goofball” — my favorite kind.

But the job took its toll. In letters to Waldvogel, Joan speaks of burnout, of frustration with her boss, of too little pay for way too much work, proving that some things never change. She also would go through periods of not feeling terribly well, though she tried to ignore all that. In her brilliant resignation letter, typed on SAIC letterhead, Flasch resigned from her post at the Store in 1985. Here’s an excerpt:

“Come MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY, (May 1, 1985), I will be abdicating the throne, relinquishing my title, headin’ up and movin’ out, retiring my number and turning in my jersey […] I’d like to take this moment to wish you the best of luck in trying to find someone to fill my boots, (I wear a size 9 ½).”

The letter is cc’ed to “a cast of thousands.”

And while those thousands wouldn’t have Joan to help them out in the weird basement anymore, they didn’t have to say goodbye — at least not yet. Because all the while Flasch was (wo)manning SAIC’s supply headquarters, she had been steadily falling in love with an art form that took her away from photography and the other art practices she had experimented with: Joan Flasch had fallen in love with bookbinding.

Bound To Happen

It’s hard to say which came first: Did Joan’s meticulous attention to the quality of papers she ordered for the Store lead to a romance with book arts and bookbinding, or did an early interest in book anatomy and their hand-production lead to her near-obsessive desire to investigate and provide students the best papers and printmaking materials poor art student money could buy?

It doesn’t matter. What matters is that by the 1980s, Flasch was fully committed to a practice that, as her mentor and teaching partner Gary Frost tells it, was in the “twilight” of existence: the fine art and science of book arts, more often referred to these days as “bookbinding.”

“There was a time when typography and book design were fundamental to art, like anatomy to drawing,” Frost said. “And into the 1950s, [bookbinding] was a thing of great prestige and expertise.”

Frost, himself an award-winning bookbinder and Conservator Emeritus at University of Iowa Libraries, painted a picture of Chicago in its hand-binding industry heyday, a world of cigar clubs, big presses down on Printer’s Row, a place imbued with the kind of madcap energy that comes when an industry finds itself becoming more or less obsolete. Without a doubt, the tides of hand-bound, “old school” printing were changing.

“All of it had collapsed by the time Joan and I met in the 1970s,” Frost said.

At least the two bookbinding aficionados had found each other. At first, Flasch served as apprentice to Frost at his studio in Pullman; there, Frost says he began to gain a “profound” appreciation for Flasch, that he learned as much from Joan as she did from him. Even in those early days, her scholarly approach to evaluating papers for artistic and archival purposes showed what Frost called “a printer’s knack.”

It’s long been true that if you’re faculty at SAIC, you can take classes at a discount. It would stand to reason that the ever-curious, book-lovin’ Ms. Flasch would capitalize on that opportunity and enroll in as many bookbinding or book arts classes as she could, right?

Not exactly. When she and Gary were doing their thing in Pullman (including putting on shows such as the first-ever SAIC “Bookbinding for Artists” annual student exhibition) there simply weren’t many book-related classes to take here. What classes were available were taught by a handful of teachers, including Frost. After she had exhausted those slim pickings, a bookbinder was on her own.

For Joan, the solution to her desire to immerse herself in a classroom where she could soak up more knowledge of what she had come to see as her calling, she’d just have to teach classes herself — or join forces with Gary Frost. So that’s what she did.

The Flash/Frost classes, Bookbinding I and II, were packed every term, bursting at the seams with 30, even 40 students clamoring for a spot. The following is an excerpt from a letter student Valarie Brocato (BFA ‘89) received from Joan one summer before school began:

Dear Person Registered for Beginning Bookbinding Class,

It is extremely important that you attend the first bookbinding class this fall. The class is already over-enrolled and there are Teeming Millions on a waiting list! What those Teeming Millions are waiting for, is for someone to not show up for the first day of class […] I’ll see you the first day of class or you will make one of those Teeming Millions people very happy!

Cheers!Joan Flasch

(I’m the teacher)

Aside from the interest this kind of letter created, part of the buzz for taking Bookbinding was due to the rather reckless moment the book as object was having in art culture at the time.

Book Arts: Don’t Call It a Comeback

Just as it’s important to understand the SAIC of the 1970s in telling the tale of Joan Flasch, it’s important to pause for a moment and examine the whole notion of artists’ books; more specifically, the difference between the making of artists’ books and bookbinding or book arts. (Prepare to scratch your head, but take comfort that the rest of the art world has been scratching right along with you for years.)

The question at the heart of the ongoing, often heated discussion about the difference between — even the very existence of — “artists’ books” and hand-bound, labor-intensive or otherwise fancy books comes down to a simple question: Are books art?

We’re not talking about mass-produced books you buy at the airport. When we talk about books as art vis-à-vis the fine art world, we’re talking about the kind of labor-intensive, small-batch books that so transfixed people like Joan Flasch, Gary Frost, and their contemporaries in the book arts. The roots of all that go back a long, long time (illuminated manuscripts, anyone?), but at SAIC in the seventies, there was a new wrinkle in the conversation.

To book nuts like Joan Flasch, calling a book a work of art was redundant. It was like, “Yeah, books are art. Can we get back to saddle stitching, now?”

But suddenly, a new wave of artists (and scholars right behind them) began making a distinction between hand-bound books and what could be thought of as “book-like objects.” Though there is still a raging controversy around where exactly to put the apostrophe, these objects were thus dubbed “artists’ books.”

An artist’s book is roughly defined as “a work of art that utilizes the form of a book.” Think of an artist’s book more like sculpture, less like something you’re supposed to curl up with on a rainy day — but don’t let the term “sculpture” mislead you. It’s not that artists’ books are carved from marble or cast in bronze; it’s more that the book as form is used as the medium for an artist’s intention.

A lot of people were really stoked about this new-school thinking. After all, bookmaking was becoming more democratic as printing giants were crumbling and user-friendly print shops like Kinko’s (founded in 1970) were popping up everywhere. Zine culture and small-batch or one-off artists’ books were demanding attention, eschewing what some saw as elitism around the kind of artisanal craft bookbinding to which Gary Frost and Joan Flasch were so dedicated.

How did the bookbinders feel about all this? There were plenty of left, right, and center positions to take, of course. In the case of the Flasch/Frost team, the conversation itself was the important part, as it ultimately confirmed books as being objects of artistic importance, however you categorized them. And even if they were still grappling with their personal feelings on the matter, the duo was savvy enough to adapt to the cultural moment.

“We picked up the theme ‘Bookbinding For Artists’,” Frost said. And just like that, the name of their class was changed.

“In doing that, we crossed that bridge [in examining] the prospects of the book format for artists, maybe a new concept for us, but also a dawning concept in the larger sense. It was a pivotal time.”

Frost notes that the work being done at SAIC back then — and the guidance he and Flasch were giving to hundreds of students every year — contributed greatly to the conversation around artists books back then. Then, when Frost made a move to New York in 1981, Flasch flew solo, teaching their mega-popular classes on her own.

Sally Alatalo was a student of Flasch’s from 1986-1987 and found herself in the middle of what Frost described as that “schizo” moment in the book/art world.

“I entered Joan’s classes looking for the relevance of bookbinding,” she said, “how these artisanal objects reconciled my position of books being democratic.”

Alatalo said that over the course of her time in Flasch’s classroom — where every last detail had been thoughtfully prepared by her teacher down to kits she made for every student — she began to foster a deep respect for the craft she had been initially so skeptical about.

But for Alatalo and so many others, this dynamic conversation was only getting started when Joan fell ill. And so began the painful — which is not to say final — chapter of Joan Flasch’s remarkable life.

‘I Married My Dentist!’

Before we get to the hard part, some good news. While Flasch was doing her bookbinding, team-teaching, Student Store-rocking thing, she was also falling in love. With her dentist.

Bruce Scheff, D.D.S., who had been living in Chicago for some time, was a satellite member of the cadre back on Surf Street. Waldvogel told me many SAIC students, including Joan, went to Scheff for all their cleaning and filling needs.

“I had never dated a patient before Joan,” Scheff told me. “But at some point we got dinner and I just so enjoyed being around her. She had this wonderful personality.”

Bruce and Joan’s relationship progressed and before long, Bruce proposed. The couple moved into Bruce’s place on Printer’s Row. (One imagines that for bookbinder like Flasch, a pad in that legendary location was a major point in Scheff’s favor.)

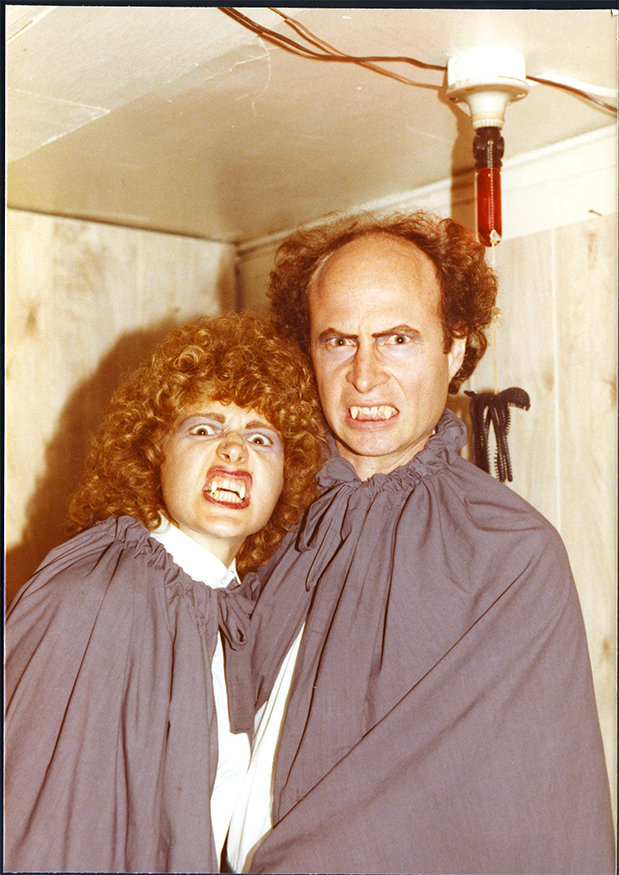

They had a lot of fun. Joan adapted dental tools for bookbinding purposes, crafting leather handles for scalpels and setting up a bindery in the second bedroom; Bruce fashioned acrylic vampire teeth for their Halloween costumes. They got married in March of 1983 and things were basically amazing. Joan was looking forward to starting a family. Her classes at SAIC were hot. She was making books and selling them. She was curating book exhibitions around town and enjoying her ever-widening circle of friends.

But there was trouble on the horizon.

In 1980, a benign tumor was found in Joan’s pituitary gland. (It just so happened two of her friends had the same diagnosis; Joan called the three of them “The Tumorettes.”) Her treatment seemed to be a success, but in January of 1987, she was diagnosed with cancer in the same area.

After chemotherapy and subsequent surgery in Chicago, Flasch began aggressive radiation treatment that would take her to Livermore Labs in Berkeley, California, to try and stop the cancer’s progression. Scheff remembers his late wife trying out a wig when her hair fell out, but opting instead to create her own fabulous headscarves, which she called her “urban turbans.”

And for awhile, things looked okay. Scheff and Flasch traveled and the rockstar bookbinder went back to teaching in the fall of 1987. Joan completed the spring term, too, though the treatment was hard on her.

Through it all, however, Waldvogel said Joan remained chipper, at least on the surface; letters to her friends at the time always more focused on their lives, not hers.

The positive attitude may have bolstered her spirits and perhaps eased some of the pain and fear in the people around her, but it couldn’t save her body from the ravages of the cancer and subsequent treatment. Though she valiantly tried to manage her courses that fall, within a couple weeks Joan was too ill to go on. She reluctantly handed over the reins to her classes and continued to follow doctor’s orders.

On September 28, 1988, less than two years after her diagnosis, Joan succumbed to complications from her cancer treatments. She was 39.

Joan Flasch: Rest In Books

On November 19, 1988, the Chicago Stock Exchange Trading Room at the Art Institute opened its doors to the hundreds of people who had come to celebrate and remember the vibrant and remarkable life of Joan Flasch.

“It was standing room only,” Betty said. “We were grateful and surprised to see that many people — except of course that it really wasn’t surprising at all that so many would come out for Joan.”

Betty recalled parts of what she said about her sister that day. She spoke of her sister’s fearlessness, how Joan stood up to bullies and catcallers; how when they watched scary movies as kids, Joan would go ahead of everyone else to “check for monsters.”

Other eulogies were given by Bruce and SAIC President Roger Gilmore, and everyone agreed: The memorial was spectacular. Afterward, Scheff, in conversation with Flaxman librarian Nadine Byrne and library associate Fred Hillbruner, wondered if the growing, special collection of artist and hand-bound books in the Flaxman Library might bear his late wife’s name.

The project got the green light. With seed money from Scheff and generous contributions from friends and organizations with which Flasch was affiliated — the Art Institute, the Chicago Hand Bookbinders Association, and others — the Joan Flasch Artist Book Collection (JFABC) was dedicated that December and currently resides on the 5th floor of Sharp.

Have you been there, yet?

If you haven’t, I personally give you permission to be luxuriously late to your next class. Because you simply have to go there. In Joan’s “library,” wonders are in store — and you shouldn’t wait explore it all with the curiosity and vigor of its namesake.

You’ll find delicate papers bound by artists from the other side of the world. You’ll open heavy cloth covers to reveal stories painstakingly painted by hand. Sculptural books will confound you, in a good way. Pop-up books will surprise and delight.

And ask the librarian on duty to get out everything in the catalog created by Joan Flasch. You’ll get several hand-bound books with creamy, marbled paper Joan made herself, as well as a set of three impeccably constructed drop-spine book boxes (a specialty of Joan’s) which house her personal copies of vintage bookbinding journal Fine Print.

The labels on the spines of the boxes say everything about the lovingly irreverent way Flasch approached art and life. Volume One is labeled “Fine Print;” the next, “Mighty Fine Print;” and, rounding out the set, “Damn Fine Print.”

Damn fine, indeed, Joan Flasch.

Joan is my cousin ! So pleased to read this great story ! I knew she was talented but I didn’t know the extent of her success . Glad she is being celebrated .

Karyn Roggatz Ness

Park Ridge, IL

Thank you for this damn fine tribute to Joan. She was a great teacher and a vital link in the transmission of knowledge about bookbinding and book arts. I studied with her in 1985 when she was at the top of her abilities, she was so funny and sharp and terrifyingly smart. She inspired many people to teach. Some of her students went on to start book arts organizations, including the Columbia College Chicago Center for Book and Paper Arts, which had a twenty-three year run and is now fading away; her influence was felt there and continues in the work of its alumni. Joan was a huge part of Chicago’s book arts renaissance. She made SAIC more delightful. She is much missed.

One of my first jobs was in the school store, and she retains the title of “Best Boss,” to this day. I moved away and we were pen pals through her illness. She never stopped being upbeat and funny.

One day in response to an employee’s remark on the ebb and flow of the school store, Joan uttered a spoonerism which so amused her she kept it posted above her desk: “It’s either fast or feeman!”

I love you Joanie. RIP.

Makes me want to hop on a plane to Chicago right NOW.

Such a lovely piece of writing.

wonderful article, thank you linking us to it – Mary Fons is a rock star in the Quilt World by the way….

Stirs up fond memories of being in Joan’s class in the ‘80s… still have my books from then. And completely forgot about the wonderful world inside SAIC’s school store!

Mary, thank you for this great article about Joan Flasch. It brought back great memories of that time. I was working at the SAIC while Joan was a student, we were friends, we were students in the same bookbinding class with Gary Frost, Bruce Scheff was my dentist, she was the maid-of-honor at my wedding in 1970 and for while, I was her boss, etc., etc. etc.

Your research was incredible. To the best of my memory, you got everything right. She was a wonderful person. Your article brought back great memories.

Thank you.