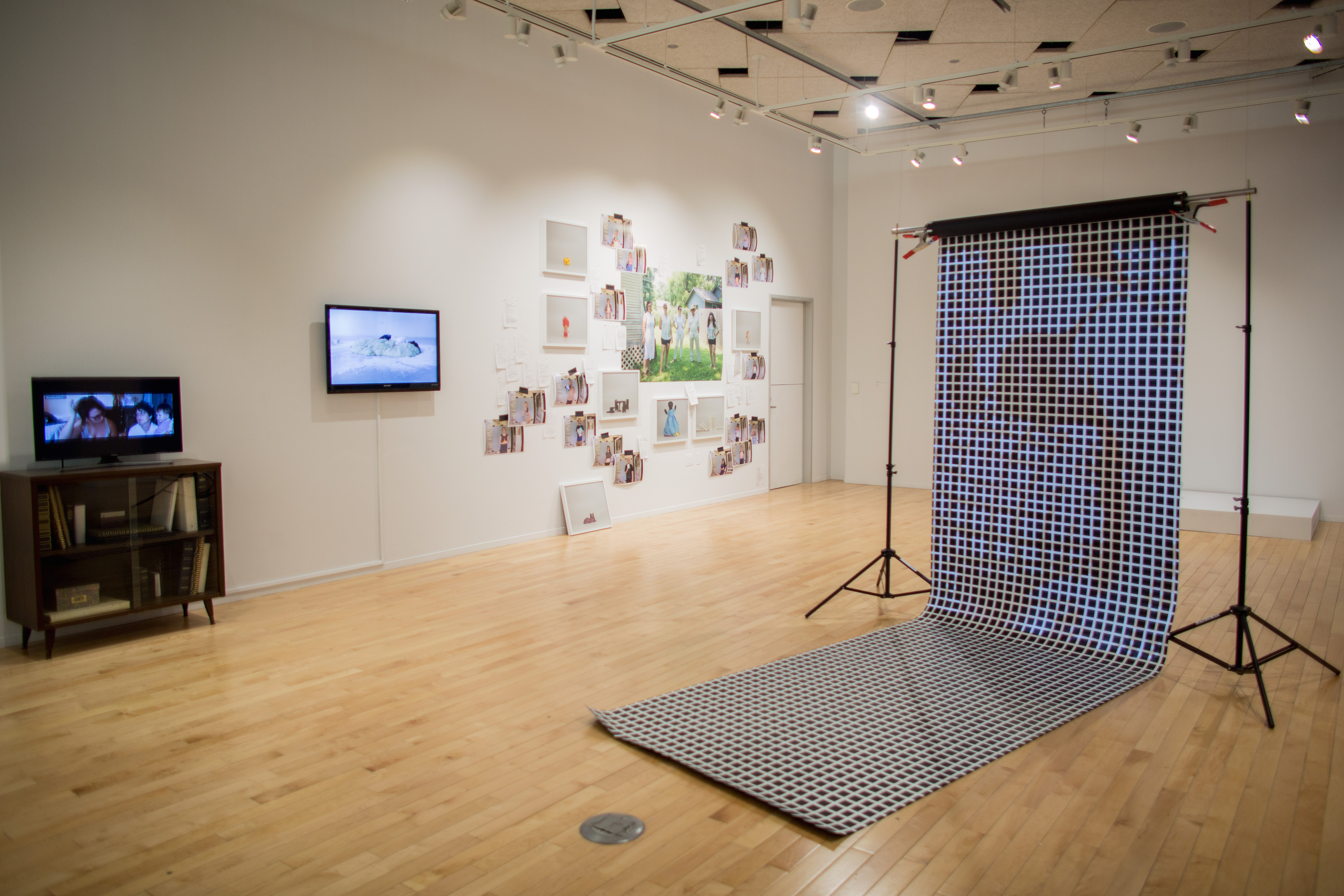

What I first noticed about the Student Union Galleries’ (SUGs’) newest exhibition, “Bearing: Object, Body, and Space,” was the way in which artist Michelle Marie Murphy’s work invites the viewer into the gallery. It stands at the window, a grid as a metaphor for the body, beckoning you to step closer. The whole exhibit is urging the viewer to pay a visit to the LeRoy Neiman Center Gallery and see what the grid builds inside the white space.

Murphy draws on the viewer’s curiosity and the gallery’s location to reassert ownership of her body — a body made vulnerable by a society constantly trying to legislate, police, and objectify its functions and presentation.

Murphy’s “The Body as Renewable Resource” and “My Body in Relation to a Grid” are almost quite literally two sides of the same coin, in their presentation and in their interpretation. The glittery, metallic sheen that covers the body in the former both highlights and hides the vulnerability of the body; the grid abstracts this body, reminds you that a body is first and foremost a physical vehicle for a person who thinks and creates and reflects on herself.

Murphy moves this gaze back to the viewer in “Your body, the Grid, and a Projected Figure.” She invites the viewer to look into themselves and to realize that their bodies are physical and vulnerable and can often be reduced to measurements burdensome and inconsequential to movement through time and space.

My body is not very different from yours, but we judge each others bodies differently; this work is a reflection on the disconnect that very frequently exists between how we see ourselves and how we are seen. Murphy is telling us to watch the ways in which our bodies are being looked at, and to allow ourselves to do the looking without the lens of the outsider gaze.

Santina Amato’s work highlights the vulnerability of the body in its excesses and yearning for affection while Murphy focuses more on the body’s need for attention. Amato’s “Untitled Dough Project (Body Time-Lapse),” is a performance piece depicting her holding dough and rolling in it, letting it swallow her and re-emerging from its midst in a mesmerizing loop. Watching the video of her lying on the ground made me feel exposed, suddenly hyper-aware of my own need to be held and comforted. The dough, although malleable and accommodating, stood in for a caring partner or an affectionate friend, absorbing the role of both while still lacking.

Amato’s “Untitled (Performative Sculpture 1)” brings another aspect of the body’s vulnerability to the forefront. It made me think of the excesses of the body, the body’s waste, the body’s attempts to keep itself clean by pushing out that which is unclean. The dough slowly dripping from the pipe evoked a visceral disgust in me, reminding me of the bodily functions we try to hide and don’t want to acknowledge. In acknowledging it, however, Amato reasserts her bravery and her commitment to examining the body and it’s functions and desires.

Amato’s “Green Room” is startling because of it’s vaguely erotic presentation. Watching the video, I can tell that I’m looking at a naked body but I don’t know which part of the body it is. It moves, jerks, halts, and dances to a rhythm I’m unaware of but one that is deeply familiar. Looking at the laptop propped sideways on the shelf, I want to right it, take a step back or zoom out to learn more about this moving body and connect it to my own moving body, as though identifying the body part would allow me to relate to it more deeply.

Lindsay Hutchens takes a different approach to the concept and presence of the body in a gallery space. Hutchens examines the history of the body within the context in which it is shaped and moulded and the things it claims ownership of.

In “(m)other” Hutchens records herself trying to mimic a picture of her mom gazing into the distance. Hutchens does this with a bittersweet humor, like a kid trying on her mom’s lipstick and high heels when she’s looking the other way. Hutchens is trying on the role of the mother, holding her cat up to the camera like her mother is holding a baby (presumably Hutchens herself) in the photograph. Hutchens is aware of her uncanny resemblance to her mother and the video of her trying to capture her mother’s gaze is propped up over a cabinet of old photo albums. While the cabinet is closed and the albums aren’t available for public viewing, it’s easy to imagine many more photographs of Hutchens and her mother in them. The albums hold histories Hutchens is drawing out in her work.

Hutchens takes this history one step further in “Heirless”, a series of photographs and questionnaires of a yard sale in which she sells childhood items to friends and strangers and asks them to vow to never give her back these items. Hutchens poses an interesting question; who are we without the objects that hold our memories? Is it enough for the body to house these memories? I think, in this piece, Hutchens is stating that yes, separation is painful, it’s easy to want to hold on forever, but letting go is where creation starts and maturity happens.

Ultimately, the exhibition grapples with the relationship between the artist and the body. It reminds us that as artists, we can’t separate the physical space we inhabit from the work we create. It puts the body at the forefront and examines how we can make the physical space ours, whether that is the gallery or our bodies.

“Bearing: Object, Body, and Space” is on view at the LeRoy Neiman Center Gallery though March 23, 2017.