Mention “Fortnite” in a sentence to anyone and you often get the name repeated back at you in one of two ways — excitement, or utter disdain.

It’s the most popular game in the world, with its player base cumulatively racking up almost 10,420,000 years of collective gameplay time in 2020, three years after its release. But of course, you don’t get to 8 million daily logins without having a few detractors. “Fortnite” is made fun of as much as it’s taken seriously, despite its status as a cultural reset for the gaming world at large. And up until recently, I, too, was firmly in favor of making fun of it.

There are many things to unpack in that last sentence. Yes, I am now a “Fortnite” convert. Yes, I have really and truly eaten every single mean word I ever said about “Fortnite” in the past. And, to all the “Fortnite” fans I made fun of before, I’m sorry.

To the “Fortnite” skeptics reading this, you may be wondering what the hell happened. You may see my newfound status as a “Fortnite” player as a sign of bad taste, mental degradation, or an irreversible regression into a childlike state of being. I’d respond to that with a request to hear me out. As a former skeptic myself, my journey to “Fortnite” enlightenment — Fortlitenment?! — knocked down all my strongest objections to the game, or at least, what I thought the game was. But “Fortnite” has come a long way since its release in July 2017, moving as fast as the changes we’ve seen in gaming, popular culture, and Gen Z internet habits. It is on these strange new grounds that “Fortnite” ultimately finds fertile soil.

The major problem that many older and more experienced gamers have with “Fortnite” is that, as a game whose assets and mission have been reworked and cannibalized to death, the game lacks any real “heart.” To understand this criticism, we must travel back to 2011, the year that Epic Games first revealed “Fortnite” was in development. Six years before its final release in July 2017, “Fortnite” was marketed as a horror game: the unholy lovechild of “Minecraft” and “Left 4 Dead” that would pit teams of four players against monsters that Epic Games art director Pete Ellis called “really, really terrifying, over-the-top scary.” This narrative ran all the way up to release day — the primary game mode in “Fortnite” was called “Save The World,” cost $40, and focused on base-building and player-vs-environment (PvE) gameplay.

The “Battle Royale” mode that “Fortnite” is best known for today — hell, its official title today is actually “Fortnite: Battle Royale” — did not emerge until after “Save The World” had been paid for by, and shipped out to, players. Since March 2017, Bluehole Studio’s “PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds” (PUBG) had been dominating the gaming world, proving that a free-to-play game could be sustained exclusively through high-volume microtransactions, as well as the viability of the battle royale genre as a whole. Development of “Fortnite: Battle Royale” was done in just about two months (under what I can only assume were some insane crunch conditions), and was released in September 2017 as a title separate from “Save The World” that would, unlike its sister game, be free to play. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Today, “Fortnite: Battle Royale” is just about all anyone knows about the game. “Save The World” has been relegated to an afterthought for most players and the Epic Games team alike. The original game mode is now packaged in with the whole game client but receives only a fraction of the attention, updates, and development that “Battle Royale” does, despite the fact that it was “Battle Royale” which had initially been the afterthought; the cardboard tail tacked on the donkey to capitalize on the success of “PUBG” and rake in more cash. Initial gameplay of the “Battle Royale” mode revealed what most early backers of “Fortnite” had predicted all along. The game’s assets had been half-heartedly re-purposed, like you were meant to be playing one game but had been given another. There was no longer anything at the core of “Fortnite” but a bare-faced cash grab. The game had lost any heart it had.

And then it got big.

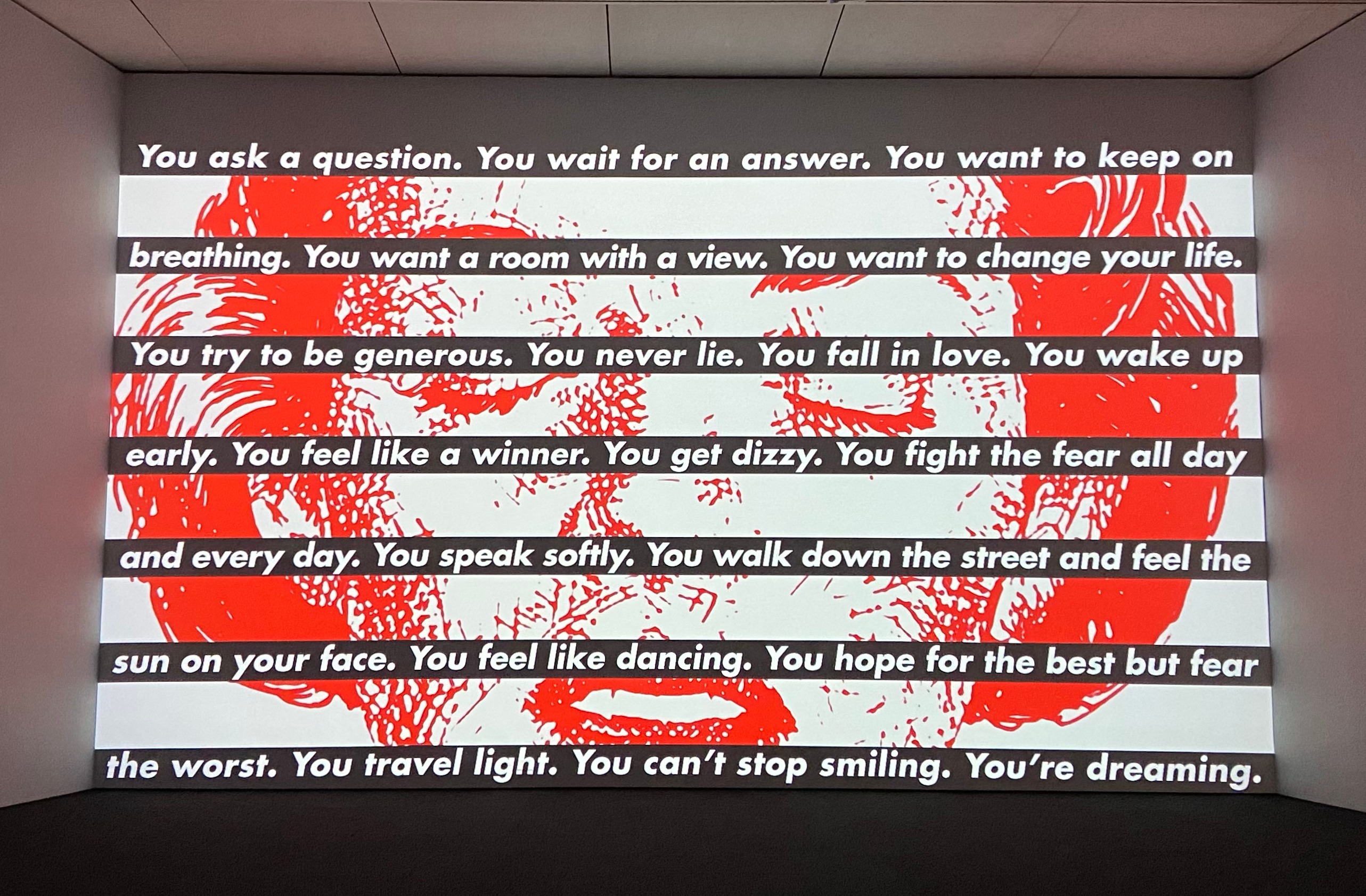

The boom in popularity that “Fortnite: Battle Royale” went through post-release was one of nuclear proportions. The game’s T rating by the ESRB opened the game up to a flood of younger teenagers (and, in some countries, twelve-year-old tweens) who were eager, impressionable, and often backed by their parents’ hefty wallets. Suddenly, everyone wanted a piece of that “Fortnite” pie. Just about every major franchise and intellectual property were launching collaborations with “Fortnite,” from Marvel Studios and DC to Balenciaga and just about every team in the NBA. Travis Scott and Ariana Grande held virtual concerts in “Fortnite;” the latter pop star is currently still in the game as both a wearable skin and an NPC who gives out quests. More recently, the games have even made nods towards social justice, hosting both a Civil Rights Movement remembrance event and another called “We The People” which aimed to raise awareness about voter suppression in the United States.

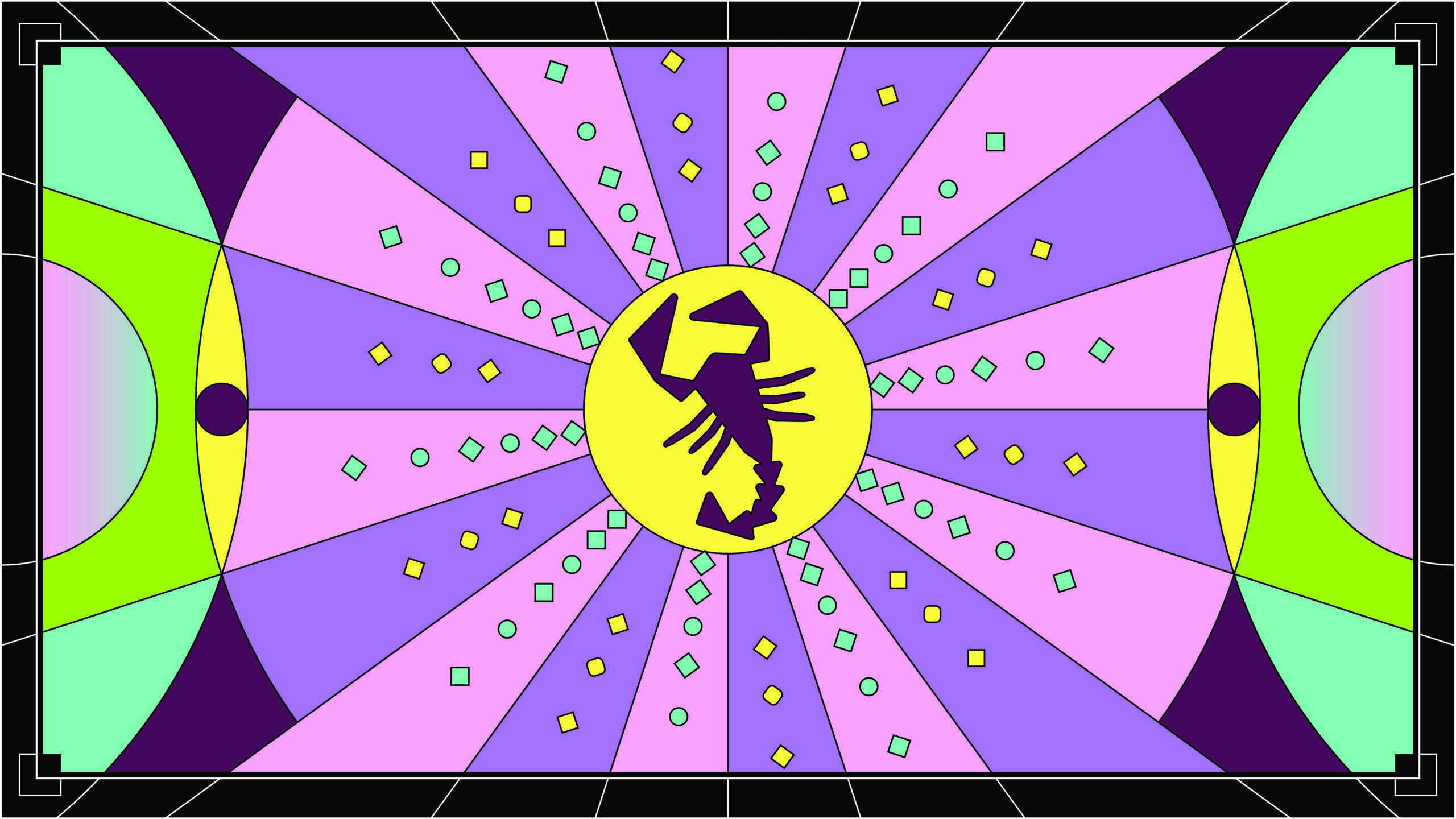

Coupled with the new “Creative” mode in which players could create custom levels and game modes — the most popular of which currently includes a “Squid Game” simulation — “Fortnite” was steadily evading classification as just a video game. It was becoming something more akin to “Second Life,” a virtual world in which you can be literally anything you want, from Pickle Rick, to an anime girl, to my personal skin of choice, Timothée Chalamet as Paul Atreides in the 2021 remake of “Dune.” In this postmodern oasis of crossed wires and information overload, the possibilities are endless. And in a way, even the stupendous and forbidding number of in-game shop options are forgivable, considering that none of these cosmetic items give you an in-game advantage and are generally affordable if you’re looking to just get one skin and stick with it. There is absolutely no pressure to have your character look like Wonder Woman as you run through the Boney Burbs — but if you want to, the option is yours for about $8.

It is this facet of “Fortnite” that has, in my opinion, helped the game transcend its need to have any kind of “heart” at all. In a turn of events that would have Jean Baudrillard cartwheeling in his grave, the fact that “Fortnite” is now an amalgamation of money grabs from just about every major piece of popular culture out there today has created an in-game atmosphere so absurd and hyperreal that it is impossible not to be swept up in it the moment you first jump off the Battle Bus. In true postmodern fashion, why have a heart when you could, quite literally, have everything else at your fingertips?

When we play video games there is already an innate willingness to suspend most of our disbelief at whatever we see. When taken into account alongside the contemporary currents of surreal Gen Z humor and the light speeds at which TikTok viral culture moves, “Fortnite” doesn’t just encourage your suspension of disbelief, it facilitates it. In the same way that we’d laugh at “Stonks” memes or nonsensical viral YouTube videos from surreal entertainment or Timotainment, how could you tear yourself away from the sheer absurdity of a video game in which you can engage in a four-way shootout with Captain America, Ariana Grande, and a unicorn that vomits multi-colored cereal? How could you not laugh after dying in second place as the winner who shotgunned you in the face immediately starts dancing to the sound of “Dynamite” by BTS? In the same way that we keep scrolling through TikTok, Instagram reels, andviral YouTube recommendations, “Fortnite” keeps you coming back for that same vein of humor. No match is like the last, and the perpetual motion machine of its never-ending collaborations with just about every big franchise out there is what will presumably sustain its brand of addictiveness for plenty more years to come.

Of course, the gameplay and the way it looks is an added bonus. As someone whose gaming history involved a high-stakes e-sports atmosphere — I entered the qualifying rounds for the United Kingdom “Splatoon 2” Championships but ultimately did not make it — and experiencing unquantifiable amounts of race-based verbal abuse at the hands of teammates on casual “Overwatch” and “VALORANT” matches, coming into “Fortnite” felt like I was finally playing a game I could actually sit back and enjoy. In a game that pits 100 players against each other in a rapidly-shrinking map, there is no real “loss” outside of a Victory Royale, just your placement number. Provided you aren’t extremely competitive, it’s easy to see the lack of a possible “defeat” as a low-stakes game. The violent claustrophobia of small-map tactical shooters like “VALORANT” and “Counter Strike: Global Offensive” are gone too, replaced by a large fantasy-setting map and more emphasis on resource management and foraging than all-out glory and gore. Perhaps best of all, there is absolutely no pressure to speak to anyone in this game. Team dynamics in co-op games are simple enough that most players leave their voice chat disabled, and there is enough safety in that silence for players to have a comfortable gaming experience by themselves.

The way “Fortnite” then sets itself apart from the other battle royales out there is its oft-debated art style. Boasting much more cartoonish designs than its contemporaries, “Apex Legends” and “PUBG,” the art style of “Fortnite” has attracted plenty of derision from older gamers who dismiss the game as being only for children, and from younger gamers who prefer more realistic and immersive shooter experiences. To me, this is simply a question of taste. In the same way stylized 2D animation is often cast aside by bigger studios in favor of hyperrealistic 3D models straight out of the uncanny valley, the saccharine-sweet world of “Fortnite” might not be for everyone. But for those who appreciate it, it will only serve to emphasize the game’s compelling absurdity. After all, if there’s one thing more surreal than watching Captain America, Ariana Grande, and a vomiting unicorn engage in a shootout, it’s watching them do so as cartoon characters. And who wouldn’t want to see that?

I spent four long years treating “Fortnite” with the utmost skepticism. In a way, I was right to do so at the start. But the way that “Fortnite” has transcended its roots has cemented it in our collective consciousness as the biggest, most bombastic, most Gen Z game we’ve ever seen — and, as I’ve shown, for good reason. Still skeptical? Try bursting your gaming bubble sometime. The worst that could happen is that you find it’s not for you. The best that could happen, among many other possibilities, is that you could see Thanos hit the dab. Anything goes with postmodernism. Need I say more?