After my dad saw “Dunkirk,” he flattered me by requesting that I write about it. Instead of adding my voice to the plethora of better-qualified critics, I decided the only person the world should hear from about this movie is the very man who requested the article. Thus, the column “Dads on Film” was born.

What follows is my interview with Philip Rich, Chief Market Strategist at Seaside National Bank & Trust, history buff, and father of three.

Emily Mercedes Rich: What did you think of “Dunkirk”?

Philip Rich: I thought it was a fantastic movie. It was very different. I thought it was visually really amazing. I thought it was also very interesting because usually these stories are told from the perspective of the generals, or Churchill, or the top decision-makers. This was all from the point of view of the participants. Even when Churchill speaks, he speaks through one of the soldiers at the very end who delivers his speech in a very flat tone. I liked it a lot. But I also wonder how many people in America have any clue as to what the historic placement of Dunkirk is. Even in my own office — I recommended it to a few folks — they were sort of like, “Well, what’s Dunkirk?” It was clear to me that they didn’t know what the context was.

I think most Americans have forgotten that World War II, in Europe, was going on for over two years before America was involved at all, and our first attack was in North Africa — it had nothing to do with Europe. In the Pacific, it had been going on for five years before Pearl Harbor, depending on when you count the beginning. I don’t think they did a very good job putting it into context, but then they probably did that on purpose too saying, “to the guys on the beach, historical context wouldn’t have mattered either.” I thought it was very well done.

EMR: I agree with you. I also had the thought about whether or not an American audience had enough to explain, aside from Kenneth Branagh’s character sort of explaining — but not in any kind of detail — why it was important to get the soldiers off the beach.

PR: I should think there are some Americans thinking, “where are the D-Day guys? Where’s Patton in all this?” At the time of Dunkirk, Patton was running training exercises in south Georgia, I believe.

EMR: I’m sure there was some throwaway line from the President, “our thoughts and prayers are with those men,” but there was no engagement at Dunkirk from the American military. And because the American school system is so insular in that it focusses on American involvement primarily, if not exclusively, you do wonder if anyone knew about it. I know I didn’t learn about it in school.

PR: It’s completely lost, and it’s a great story on many levels. Of course, militarily remember this was a defeat. This was a retreat. They had been soundly beaten, both the French and the British, and they were completely encircled. So this was a terrible defeat. But the other thing that makes it so unique — and of course what it’s remembered for — is usually the military is there to protect the civilian population. In this case, the civilian population saved the military.

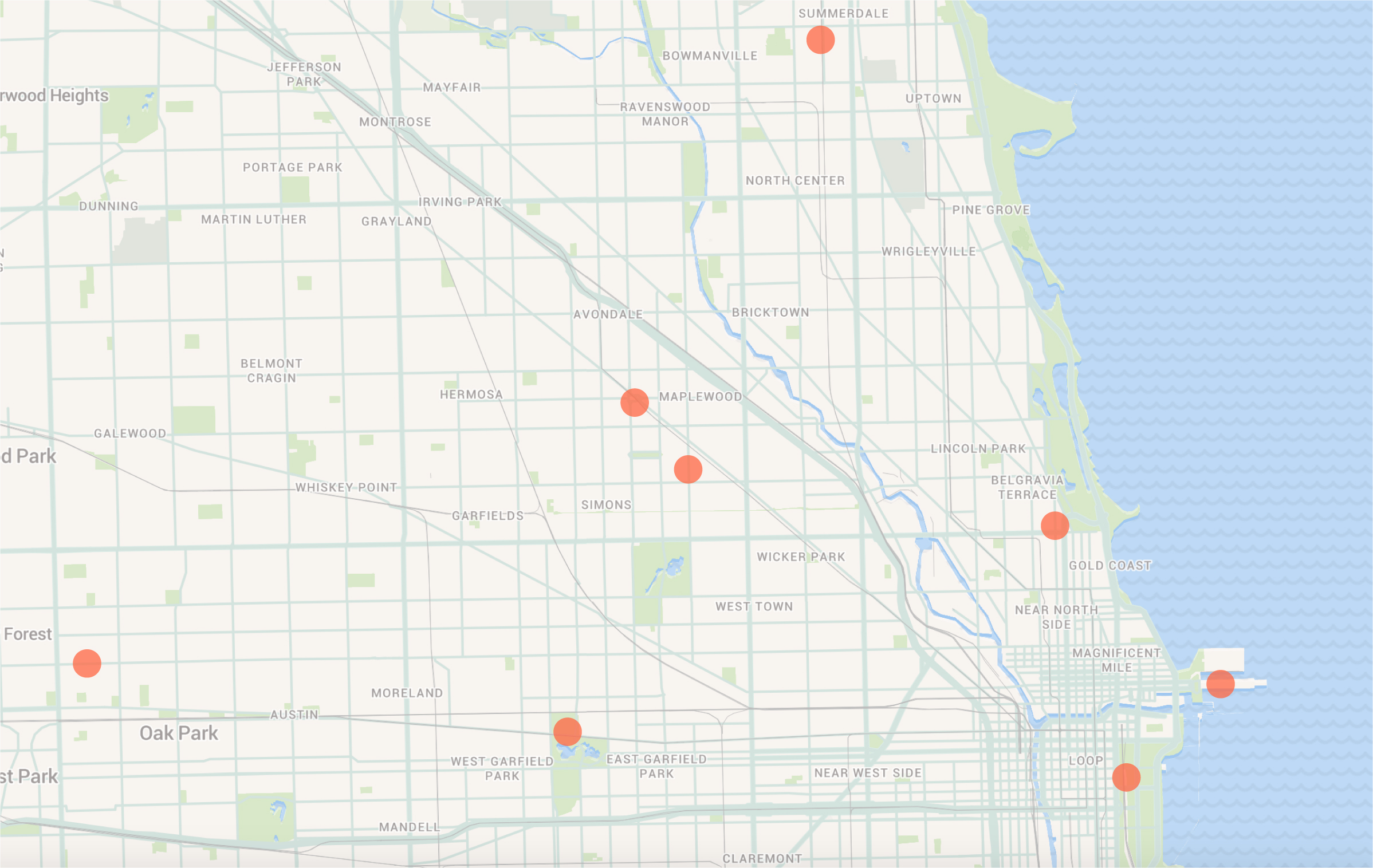

EMR: Because they lent their boats [to the Navy] or they came over the channel on their own which is one of the more emotionally-charged chapters in the movie: that civilian boat you’re with.

PR: Over a thousand civilian boats were involved. If you want to compare, there’s actually an earlier black and white movie on the same subject. [It is also called “Dunkirk”.] It’s in a very different style. [. . .] It’s been forever since I’ve seen it, but yeah, it’s a unique story. [. . .]

Also part of the context of the movie: This is an island. It’s a nation of sailors. When they needed to rescue the army, a lot of them said, “Wait a minute, this is something we know how to do.” The boat portrayed was a family boat — a leisure boat — a lot of the boats were fishing vessels which, if you empty out the fish, have big holes that could hold quite a few men.

EMR: “Dunkirk” follows a tiny little boat. Of course, they have the shot toward the end of the film with all of the boats coming over, and they vary vastly in size. For an American audience, and our readers, can you explain why Dunkirk was an important military retreat for Britain and for France?

PR: If you start with the Munich Conference — which preceded the shooting part of World War II — Neville Chamberlain was still Prime Minister of Britain, and he goes and he meets with Hitler and Mussolini. Everybody in the world knows that the war is coming. Hitler has already annexed Austria, and [is about to take the Sudetenland]. He’s also already marched into the [Rhineland]. They’ve also stopped paying reparations. The French are represented at Munich as well. [. . .] What happened at Munich was that [Hitler] agreed not to take anything more, and France and England essentially said, “Well, ok, we’ll live with what you’ve already done, and we won’t attack you,” but they also said, “if you attack Poland, they are an ally, and we will be at war.”

EMR: And of course then they attacked Poland.

PR: Not right away, but in about a year, Hitler attacks Poland. Immediately, France and England declare war on Germany, and for a time, nothing much happens. It’s called the “Phony War;” it almost lasts a year. [. . .]

When all this is going on, after Poland fell, Britain made Winston Churchill their Prime Minister thinking, “this Neville Chamberlain who bargains away Europe to Nazis probably isn’t our guy.” Winston Churchill, to his credit, had been warning about this for years. [. . .] You may wonder why more people didn’t see it coming, but to understand that you have to go back to World War I.

World War I was devastating to England and to France — to all of Europe. The number of casualties was incredible. In one day in World War I, one-hundred thousand men could die. To this day, every little village in France has a monument to the dead. You look at the list from World War I, in many cases it’s more people than living in the village today. [. . .] So nobody wanted to go to war. [. . .]

Anyway, the French were very poorly led. The French government is in disarray. They get their butts kicked. The Germans are using the blitzkrieg. They’re a mobile army. [. . .] So the British Expeditionary Force and many of the French — the remaining French — find themselves completely encircled at Dunkirk.

The bulk of the French army falls back to try to protect Paris. It’s mostly British at Dunkirk. [. . .] Every time the British would send a big ship to get them, it would be sunk by torpedoes. At this time, the U-Boats ruled the north Atlantic — or it would get bombed from the air. They lost a number of ships trying to save them.

Churchill knew that the next battle would be the Battle of Britain, and he had to start saving boats and men and equipment. [. . .] It sounds terrible, but if you’re in his position, you have to make a choice: Where do you put your resources? He thought that the very next thing that was going to happen was an invasion, and he didn’t want to lose any more boats or planes, men or equipment. The only way to get them off was if they took their small ships — too small to hit with a bomber, too many to hit with a strafe — and lift them off that way. That’s a long answer.

EMR: It is! But it’s good because you totally situated it in history all the way back to World War I which is great! [. . .] There’s not a lot of dialogue in the film, but [. . .] at the end of the movie, Harry Styles’ character is on the train, coming back home, and he’s worried that they’re going to throw rocks at him. He’s like, “they’re going to believe that I’m a coward and that this was somehow my decision.” Of course, that’s not how he’s greeted, but that was an anxiety that was depicted in the film.

PR: They didn’t lose because they didn’t have any courage. [. . .] There’s a lot of moral ambiguity in the film which also makes it great. You mention one other interesting thing about the film from a filmmaking standpoint: the dearth of dialogue is just incredible. It’s amazing how effective it is.

EMR: How was it effective for you?

PR: I think cinematographers have forgotten how to tell a story without saying the story. It’s sort of like slapstick comedy which is also a lost art. It’s a visual — something is visually funny. Now, everything is a spoken joke. Occasionally you get something that’s visually funny, but not as much. [. . .] So, I thought [the lack of dialogue] was interesting from a film construction standpoint.

EMR: It definitely makes the film stand out from other war movies. I went in thinking, “this is going to be comparable both in quality and content to something like ‘Saving Private Ryan’” which opens with the loudest scene in film history. “Dunkirk” just doesn’t do that.

PR: You’re actually wrong about the opening scene. The opening scene is at the cemetery.

EMR: You’re right. You’re right. [I mean] the scene on the beach.

PR: That’s right. [Steven Spielberg] gives you a huge leg up, in terms of not only historical context, but sort of sets the moral context. In fact, the very opening shot is the American flag flying over the cemetery, so they almost force feed you the moral context compared to what [“Dunkirk”] does.

The other thing, from a moral standpoint: One of the greatest things [Christopher Nolan] does is to show that these soldiers grab a body to try to sneak onto a boat. We can sit here in the comfort of a theater and say, “gee, they’re cheating. They cut the line. They lied about who they are and what they’re up to, and they abused that poor dying soldier to try to get on that boat.” But if you’re eighteen-years-old or twenty-years-old and you know that the entire German army is behind you and your country has stopped sending ships to get you, you would have done anything to get off that beach. If pulling a little sleight of hand would have gotten you on a boat, you would have done it in a heartbeat and probably have bragged to your grandchildren about it.

EMR: Yeah, given it worked. I think the lack of dialogue definitely lends itself to that moral ambiguity as well. He never explains why they’re doing what they’re doing. [. . .] He lets you put yourself in that position and think about why you might be pushed to grab the nearest dying man on the beach — whether you’re a paramedic or not — just to get a spot on a boat.

PR: The parallels with “Private Ryan” are interesting though because they’re trying to get off the beach and would do anything to get off. In “Private Ryan” they hate the fact that they have to be on it, but there’s an overwhelming force pushing them onto a very very similar beach. It wouldn’t be more than an hour drive away, maybe two hours, on today’s roads. [. . .]

EMR: In “Saving Private Ryan,” from the opening shot, you understand what this film is about morally, how you are supposed to feel when you watch this movie. “Dunkirk” is a little more ambiguous [in that regard], but I think [those qualities are] still there. How would you categorize that tone and that message in “Dunkirk”?

PR: [… .] Europeans, particularly the French, are terribly conflicted about their role in World War II, because—

EMR: They pretty unequivocally lost.

PR: Well, they lost, they were occupied, and then not only that but the government — the only government they had during World War II — was a collaborationist government. They collaborated with the Nazis, and they rounded up their own people — particularly their own Jewish people — and shipped them off to camps. So it’s difficult for them to feel pride about any part of it. Except of course the resistance and the number [of people] who actually participated in the resistance is probably fewer than people who say they participated in the resistance.

EMR: That seems to always be the way: Aligning yourself with the people who did right, in retrospect. If you were to give “Dunkirk” a star rating, or some other arbitrary scaled rating, what would you give it?

PR: Five stars. I’d give it five stars. If I were to make changes to the movie, I probably would try to give an American audience — I couldn’t help myself — I’d try to give them the historical context. But in some respects, it’s a greater film because it doesn’t do that.

[. . .] Also, the photography is very saturated. It’s almost like the light has trouble getting through the film.

EMR: It’s shot on seventy millimeter.

PR: But it’s not just that. It’s underexposed seventy millimeter, and some of that just gives you the climate of that part of the world. [. . .] It’s not a place where the sun shines all the time. The sun breaking through the clouds is a rare event in this film. You almost never have shadows. It’s very color saturated. The soundtrack was also very striking. It was all designed to keep pace with your heart rate — or what your heart rate would be if you were in the situations they’re in.

EMR: It’s also doing something really spectacular with keeping those timelines separate. [. . .] So those are all my questions. Do you have anything else you wanted to say that we didn’t touch on?

PR: We didn’t touch on the dad. I thought we were. That was in your [text].

EMR: You’re the dad!

PR: Oh, I’m the dad!

EMR: You’re the dad of “Dadkirk”!

PR: I thought you meant the dad in the film.

EMR: I mean, we can talk about the dad in the movie, if you want.

PR: Well he’s quite a character. But I thought the one thing where you questioned whether that would have really happened that way was when he’s told his son is dead, and he doesn’t—

EMR: Oh, that wasn’t his son.

PR: I thought it was his son.

EMR: It was his boat hand. His son was the one who was also there who lived.

PR: For some reason, I thought they were both his boys. So ok, it was his boat hand. But he doesn’t really flinch, and I thought, “Gee, he would have shown some emotion, I think.” But he’s quite a character!

[. . .] I thought it was an exceptional film. It takes a lot of guts to do those many things that differently and still be very effective.

[. . .] And the little story of the guys who pile into the fishing boat that’s sitting on the beach, that’s not floating, that the Germans start using for target practice. And they come up with the idea of plugging the holes with their hands. Well, of course, that means going over and putting yourself in the line of fire. That’s an interesting scene.

EMR: Did you want to talk about that scene in particular? Last time we talked about “Dunkirk” you talked about that scene as a metaphor: They want this boat to float so they can leave, but to do that they have to plug the holes with their hands.

PR: And then they’re getting shot at. That boat is [a play within a play].

EMR: Well, thanks, dad!

PR: I’d like to see the movie again. [. . .] I think it’s a really interesting movie.