Trauma is complicated, and Hulu’s “The Bear” is fast, stressful, and raw … almost too raw to watch because of the way it depicts individuals’ reactions to traumatic events. As a friend of mine, James Mazer, put it: “A lot of the time television presents grieving as ‘you’re doing it right’ and ‘you’re doing it wrong’… but what’s so engaging about [“The Bear”] is that it gives you rounded and fleshed-out characters who act in ways that seem fairly representative of how human beings handle difficult life events.” No one is ‘right’ here. Everyone’s perspective is simply a way of looking at the problems presented. While there are things the show acknowledges as ‘wrong,’ each decision is character-focused and driven by individual motivation and perception.

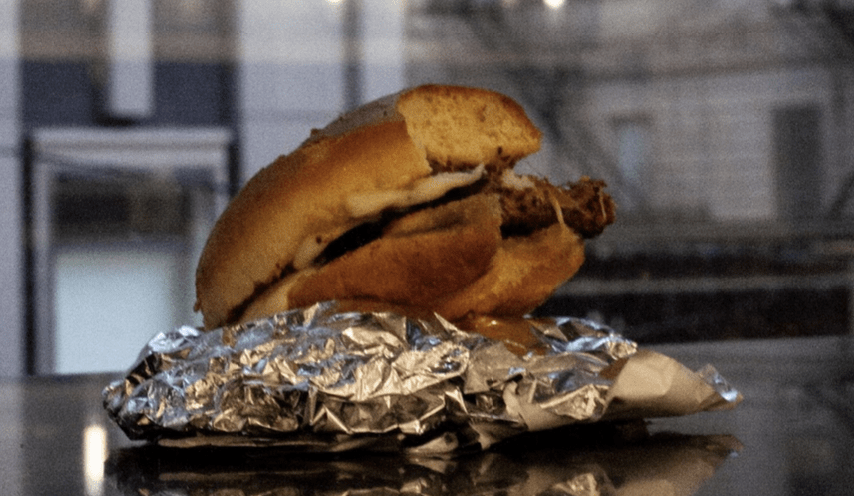

In “The Bear’s” first scene, we are presented with the disorganized kitchen of The Original Beef of Chicagoland, a.k.a The Beef. It is is now under the management of Carmen “Carmy” Berzatto — a world-renowned chef and the younger brother of the previous owner, Michael “Mikey” Berzatto — after his brother’s suicide. It is immediately obvious that the show is from Carmy’s perspective, as the staff of The Beef seem used to the grimy kitchen and the lackadaisical pace, demonstrated by an opening that feels more like a group of friends than a kitchen staff. Carmy is, when thrown into this dynamic, met with a practical and ideological division between himself and the staff, which manifests in what is referred to as ‘the system.’ The system is what is left of Mikey’s influence on how the restaurant runs, from recipes to general tactics.

Tina and Richie are the most rigid followers of Mikey’s system, and they are the ones who express the most emotion regarding Mikey and his death. Tina is a sarcastic, cutting line cook, who is very protective of how things were done when Mikey was alive. Later on, she tells Carmy that she loved Mikey, which is why she noticed the strange behaviors he exhibited towards the end of his life. Richie is also the only one we get to see interact with Mikey — he was Mikey’s childhood best friend, and we see that bond in a flashback of Richie and Mikey talking about a wild night at a party. This is contrasted in the next scene, with Richie trying to tell the same story alone and failing to land the jokes. His emotions, though indirectly expressed through brief statements and visuals, are vivid and consistent with a belief that something is missing.

A. Shaikh, a poet and MFA student at the University of Michigan, expressed their understanding of the show as someone with PTSD, specifically in relation to Carmy. “It makes sense that the ensemble cast in the restaurant is how we make sense of [Mikey] … the show wouldn’t work if we didn’t have different perspectives, especially because … [the other characters] symbolize something just so real, real in a way that it takes the whole season for Carmen to even understand, because Carmen has been following a script.” This ‘script’ A. refers to is one of Carmy as a neurodivergent-coded character, while the ‘real’ is something outside of the professional world.

Despite being the only person at The Beef who is Mikey’s blood relative, Carmy doesn’t talk about Mikey and his death until the final episode of the season. In contrast to Richie, we only see the consequences of his repression as represented in his subconscious. He doesn’t verbalize anything he feels, and the viewer only knows how he feels due to the extremely vivid nightmares and the effects of his anxiety on his physical health (such as a consistent use of Tums). He begins to consciously think about his emotions when he starts attending Al-Anon meetings at the request of his sister and hears the testimony of a woman whose husband was an addict. However, he takes the woman’s advice — focusing on what you can control and removing yourself from toxic situations — to mean the exact opposite, twisting his current situation into something he believes he can control, something that will follow his script.

In a seven minute monologue Carmy recounts how important these toxic and intense environments were to him, stating that he “had calluses on [his] fingers from the knives and [his] stomach was fucked and it was everything.” It is a script that worked, but at a cost. Mimicking this environment was a trauma response to confronting the situation that caused him to seek out these restaurants in the first place. Tina and Richie’s reactions are, similarly, trauma responses to Carmy’s changes. They are emotionally invested in the way Mikey did things and so they follow the system with reverence. They see Carmy’s changes as disrespectful to their memory of Mikey, as we see in Richie’s reminder to Carmy that this is “[his] brother’s house.” The concept of The Beef as a house, something to respect, doesn’t make sense to Carmy — he sees The Beef as a disorganized mess that Mikey never let him work in and has now, post-mortem, charged him to clean up.

The motivations of these characters are inseperable from the trauma they endured due to Mikey’s suicide. The dynamics that come from colliding memories, from learning of Mikey’s struggles with addiction, to the love he still held for Carmy and his family even at the end, are all handled beautifully and painfully. “The Bear” is a love letter to family, food, and the long and painful struggle towards healing. I think the chance it took in choosing the setting of a family-owned restaurant to showcase how trauma warps that feeling and connection, was brilliant and ended up producing a near perfect season of television.