June is Pride Month and because I make quilts, I’ve been thinking about the largest quilt in the world, The AIDS Memorial Quilt — or “the Quilt” for short. The Quilt is still offering hope and consolation to those touched by HIV / AIDS and it just so happens that a of selection panels, as well as photographs and documents related to the Quilt, are on display at Chicago’s Navy Pier through June 25.

I often get asked about the AIDS Quilt, so I thought I’d offer some information about its current status and, in the spirit of remembrance during the month that celebrates queer history and culture in America, offer a chance to learn about its living history.

Crisis, and Patchwork Inspiration

The AIDS Quilt essentially began after the 1978 assassination of San Francisco mayor George Moscone and the city’s first openly gay supervisor, Harvey Milk.

Cleve Jones, A longtime gay rights activist in San Francisco, helped organize an annual candlelight vigil for the two men. But in the years following Milk’s and Moscone’s assassinations, something else in the San Francisco gay community was demanding attention and activism: a terrifying new disease called AIDS.

The first case of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) detected in the U.S. was found in San Francisco in 1980. The virus, which causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) began to utterly waste previously young, healthy, and largely gay men at an alarming rate. The medical community could offer virtually nothing in the way of answers, let alone treatment.

When Jones realized that by 1985, over 1,000 gay men in his community had died from HIV / AIDS, he decided that the Milk / Gascone march that year would also remember those who had lost their lives to the rapidly spreading disease. Marchers wrote the names of deceased loved ones and friends on placards and taped them to the San Francisco Federal Building.

The signs looked like a patchwork quilt, Jones thought, and the Quilt was born.

From the First Stitches to the National Mall

The first panel of the Quilt was made by Jones in 1986. A year later, along with friend Mike Smith, he set about organizing the NAMES Project Foundation, a nonprofit that still serves as custodian of the AIDS Quilt and maintains its document and media archive.

A headquarters-slash-workshop opened in San Francisco’s (largely gay-populated) Castro District and was immediately flooded with contributions: Sewing machines, office and art supplies, funds, and manpower were donated to the storefront space to handle the panels that were coming in from all over the country.

Volunteers worked around the clock to sew the three-by-six foot panels — the size of a human grave — into blocks of eight. The vast majority of the panels featured the name or names of individuals who had died from HIV / AIDS, but in time there were panels included which paid tribute to nurses, doctors, and others who served valiantly in the cause.

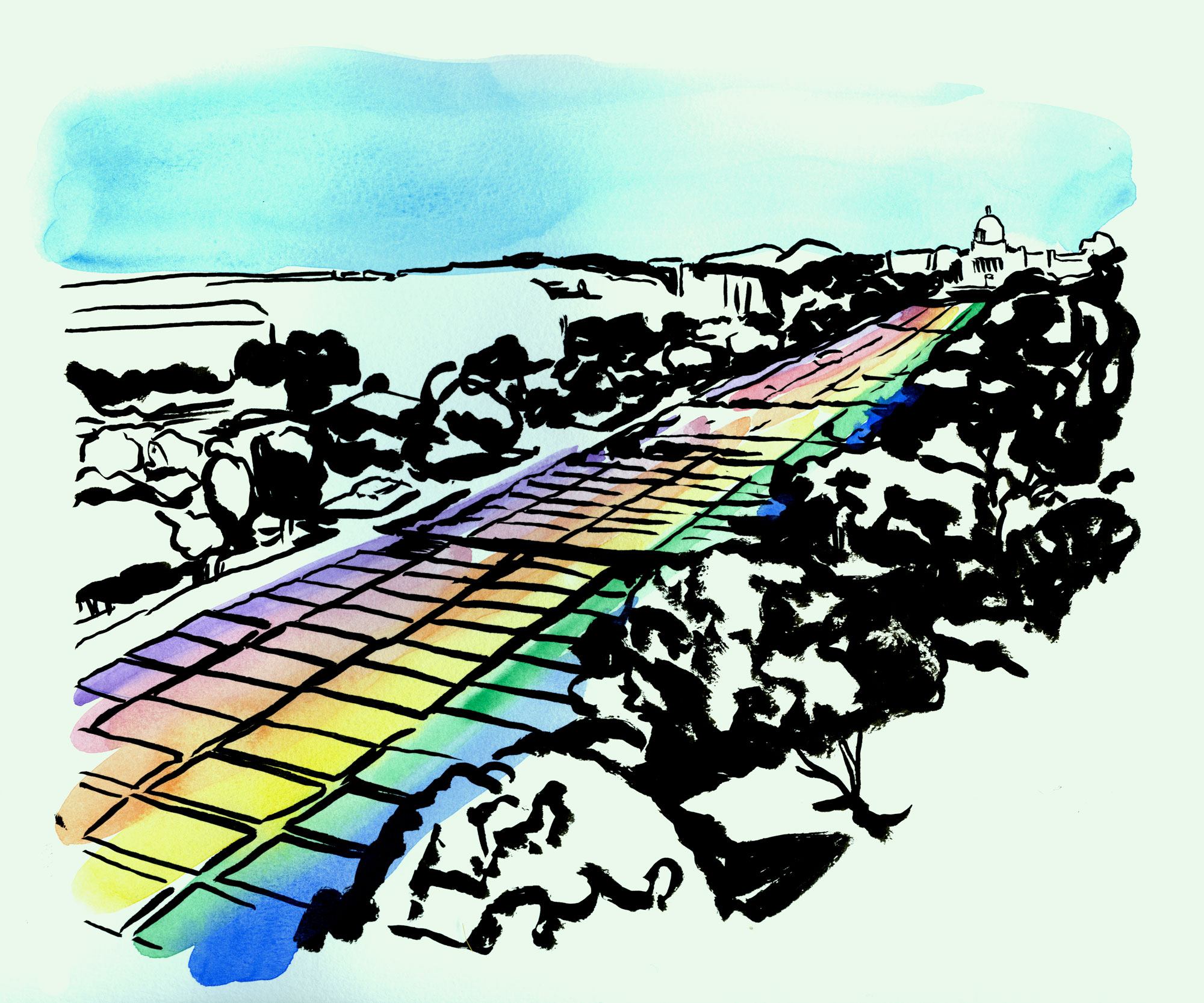

Just four months after the first 40 panels were hung from the mayor’s balcony in San Francisco, the AIDS Quilt had grown to include 1,920 panels from all over the U.S. These were the panels famously displayed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. over one weekend in October, 1987. Half a million people came to see the Quilt in order to grieve and be in community. As the Quilt was unfolded, the names of those lost to AIDS were read over a loudspeaker. Many panels and names announced were simply “Anonymous,” as the stigma of AIDS at that time was still too much for some families to contend with.

After the overwhelming response to the display in Washington, the panels embarked on a 20-city tour in the spring of 1988. Over 9,000 volunteers helped the traveling crew display the Quilt; they also helped sew panels into it as it went. By the end of the first tour, 6,000 panels had been added and over $500,000 was raised for hundreds of AIDS service organizations.

Fewer Panels = Progress

By 1994, AIDS was the leading cause of death among those aged 25-44, and science was still scrambling to find effective treatments, due in no small part to governmental red tape and societal resistance to what was initially called “gay cancer.” By the end of 1995, 534,806 Americans were diagnosed with AIDS and 332,249 had already died from the disease since the first patients were diagnosed just 15 years earlier.

Then things started to turn around — slowly. Antiretroviral medicines began to show promise in the laboratory and awareness raised by projects like the Quilt were having an effect: Safer sex was something people were taking seriously and this conscientiousness contributed greatly to curbing new infections, at least in pockets of the U.S. It was a start, however small, in changing the terrible tide of the epidemic.

The Quilt — and HIV/AIDS — Today

The good news is that the number of HIV / AIDS deaths in the U.S. have, on balance, decreased a great deal from the apogee of the crisis in the 1990s. This means the Quilt is still growing — but not at the rate it once was. That’s good.

Still, according to the CDC, there were 37,600 estimated HIV/AIDS infections confirmed in 2014, down from 45,700 in 2008. This is progress, to be sure. But there is still no vaccine for HIV/AIDS, the communities most plagued are minority and socio-economically disadvantaged ones, and worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, 36.7 million people have, to date, died as a result of HIV/AIDS.

As of June of 2016, the Quilt weighed 54 tons and comprises more than 49,000 panels sewn into approximately 6,000 blocks. Because of the size of the Quilt, organizations apply to show portions of the Quilt and many exhibitions take place across the country year-round, including the exhibit at Navy Pier this week. (The full display schedule for panels from the Quilt can be found here.)

*I recommend viewing “Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt,” the 1989 Oscar winner for Best Documentary. There are in-depth interviews with patients and loved ones making panels for the Quilt in the early years, as well as excellent footage of the original National Mall display. Flaxman can get it for you.)

*For anonymous, free HIV testing locations across the Chicagoland area, click here.

I would love to go down to Navy Pier to see the quilt. Me & friends from my church in NJ made a panel in memory of loved ones, including my brother. We were fortunate enough to have a block to display at a Walk for AIDS that year (1989?). It was very powerful. Thanks for sharing this info Mary!