On Saturday, I was helping my friend move into her new apartment when I received a text message that simply read, “Tell me you’ve seen it.” Beyoncé released the music video for her new song “Formation” — her first new music in over a year. Like her last album (“Beyonce”), it was released with no prior announcement. I had been a good and helpful friend until I received the news. I had lifted heavy boxes, unpacked clothes, and rearranged the furniture in the new space. But after the follow-up text with the link to the video, I was completely useless — totally transfixed and twerking to this radical, pro-black trap anthem.

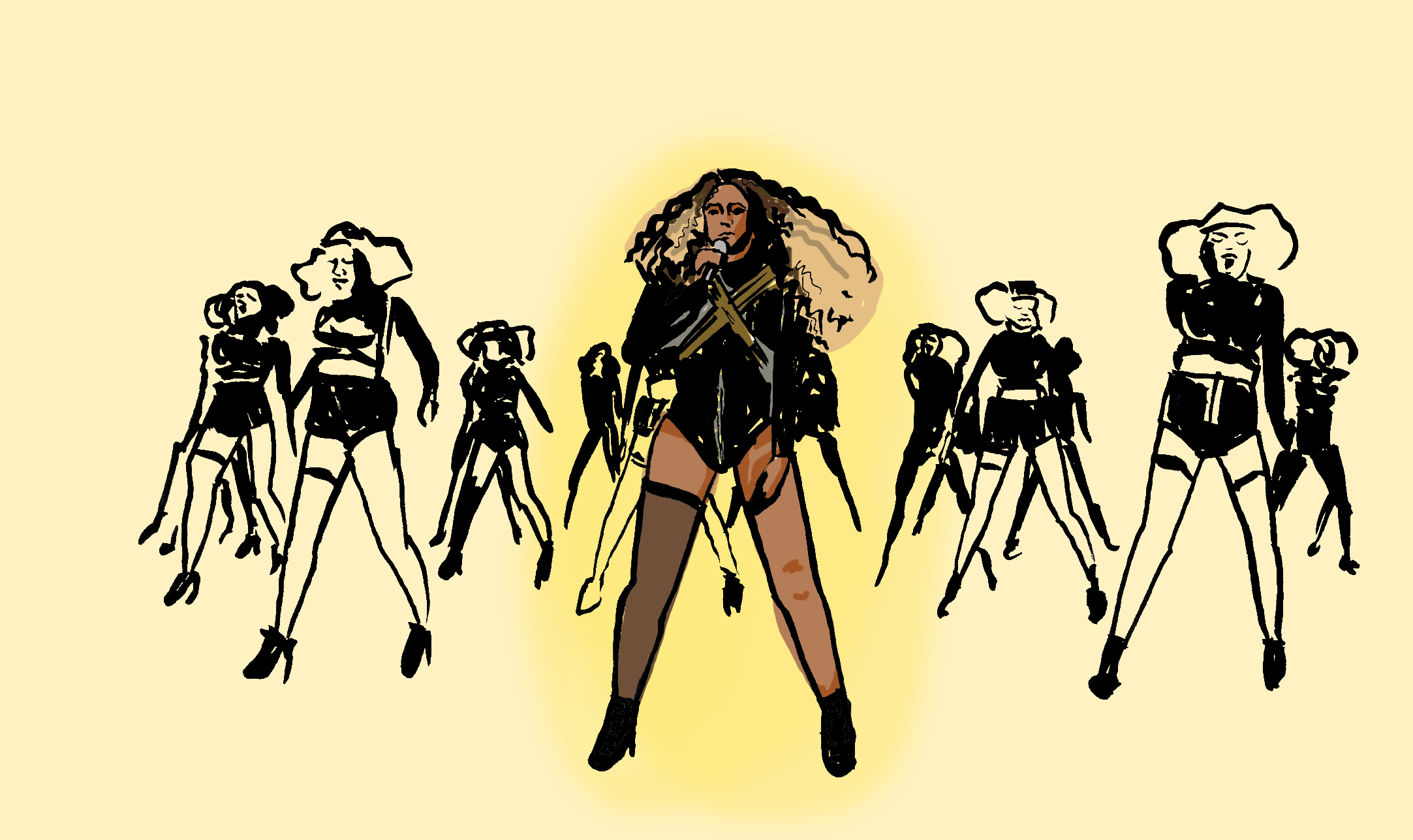

The very next day at the Superbowl, Beyoncé performed the song at the halftime show to a stadium of people who already knew the lyrics. She and her backup dancers wore costumes modeled after the Black Panthers. After the show, some of the dancers held up signs that read, “Justice for Mario Woods.” The performance was immediately followed by the announcement that she would be going on tour. Suddenly there I was, on my phone checking my bank account trying to calculate just how much less I would have to eat this week to both pay my rent and buy Beyoncé tickets. (Full disclosure: I am Level 11 regional manager in the American Midwest chapter of the Beyhive. I have followed Beyoncé’s career since early Destiny’s Child.)

This video is markedly different than a lot of her previous work — both musically and in its relationship to activism. What stood out beyond what many have already written on its pro-black, assertive message, was the prominence of black queer identity in its narrative of resistance.

In the video, black women certainly take center stage. The image of the women dancing “in formation” is juxtaposed with images of police officers also “in formation,” standing in a line across from a young black boy in a hoodie who dances defiantly in their presence. This female empowerment message is nothing new for Beyoncé: we’ve heard it in her songs “Run the World (Girls)” and “***Flawless.” However, in “Formation,” the very first voice you hear is that of the late Messy Mya (ne Anthony M. Barre). Messy Mya was a popular YouTube personality and bounce rapper.

Bounce music refers to the flamboyant dance music that originated in New Orleans. Its call-and-response borrows from both the African roots of hip-hop and Native American chants. Bounce is known for embracing queerness and gender fluidity, ushered in by performers like Big Freedia in the 1990s. An article in The New York Times further explains that New Orleans has a “long tradition of gay and gender-bending performers as part of the musical mainstream since the 1940s.” Today, in what is sometimes referred to as sissy bounce, men and women gyrate their hips rapidly to the repetitive beats of the track.

Messy Mya was famous for his popular insult videos (one of which is featured in Beyoncé’s video) and bouncing to his own songs. NPR describes the performer: “Sassy, raspy-voiced and heavily tattooed, with flowing hair in fluorescent colors, Barre demanded attention, often looking into the lens, imploring, ‘Follow me, camera!’” He was tragically shot dead at age 22, while leaving a baby shower for his unborn son.

“Formation” also includes footage of other bouncers from the documentary “That B.E.A.T.” which follows the bounce culture in New Orleans. The brief segments of the film used in “Formation” feature the dancers often from behind, shaking their backsides, with their faces away from the camera.

Entertainment Weekly reported that filmmakers Chris Black and Abteen Bagheri did not know that scenes from the film would be used in the music video and the two took to Twitter to voice their outrage. Later reports have shown that the two shot the film for Sundance and did not own the rights to the footage, and Beyoncé’s production team had gone directly to Sundance. The director of “Formation,” Melina Matsoukas, tweeted her thanks and appreciation to both Black and Bagheri.

A little over a minute into the video, we hear the deep husky voice of bounce queen Big Freedia. Big Freedia is perhaps the best known and most celebrated queen of Bounce music. In an interview with Fuse.TV, she said of the collaboration with Beyoncé:

“It was a total shocker when I got a call from Beyoncé’s publicist and she said Beyoncé wanted me to get on this track. When I heard the track and the concept behind it, which was Beyoncé paying homage to her roots (New Iberia, La.), I was even more excited! It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life and I was beyond honored to work with the original Queen B. I think it turned out amazing too!”

In “Formation,” Freedia proudly proclaims, “I did not come to play with you hoes! I came to slay, bitch!” The word “slay” is repeated in the refrain of the song as Beyoncé repeatedly proclaims “I slay” and “we slay.” The expression comes from drag ball culture and it means to do something exceptionally well. As MSNBC commentator Melissa Harris-Perry pointed out, the word is presented in an interesting juxtaposition to the narratives about the “slayings” of black bodies. Much of the imagery and the powerful affirmation of the anthem are borrowed from queer black culture. This prominence of black queerness is arguably one of the most radical aspects of the video.

Historically, some black resistance movements have focused rooting blackness in narratives of masculinity and respectability. Consequently, they have often excluded the voices of queer people. Bayard Rustin, one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s top advisers and the man who organized the March on Washington, was often condemned for his homosexuality by other black activist organizations because it was seen as a “distraction” to the movement. The Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan has made derogatory remarks claiming that the promotion of homosexuality and lesbianism in Hollywood is responsible for America’s moral decline. He even went so far as to criticize President Obama’s support of marriage equality stating that Obama was “the first president that sanctioned what the scriptures forbid.”

This is a point at which many contemporary black liberation movements differ. For example, Black Lives Matter was started by black queer women. There have been continuous pushes from within activist groups to remain intersectional — that is, to acknowledge the way systems of oppression intersect. Text from the blacklivesmatter.com reads, “Black Lives Matter affirms the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, Black-undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum.” The queerness of “Formation” seems to parallel some of that work.

It’s also important to note that “Formation” doesn’t represent the first time the singer has been explicitly political nor is it the first time she has specifically addressed race. In her last album, she identified herself as a feminist, featuring a song that sampled a speech from Nigerian writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. At the 2015 Grammy Awards, the singer performed the gospel staple “Precious Lord” with an all male chorus to give voice to the struggles of black men facing racialized police violence. She said in an interview with Billboard:

“I felt like this is an opportunity to show the strength and vulnerability in black people. My grandparents marched with Dr King. And my father was part of the first generation of black men that attended an all-white school. My father has grown up with a lot of trauma from those experiences. I feel like now I can sing for his pain, I can sing for my grandparents’ pain. I can sing for some of the families that have lost their sons.”

Beyoncé is a performer whose success is largely dependent upon her queer fanbase. In the past, the singer voiced her support for marriage equality. However, the representation of black queerness in the new music video is both a powerful and complicated one. In it we see carefree gay boys twerking and bouncing alongside empowered black women getting in formation (there may be a double meaning: the lyrics sounds like “get in formation” or “get information).” A writer and professor, Brittany Cooper, points out they quite literally form the spine of resistance. I would argue that weaving those images together in a story of black liberation is radical in its own right.

However, as some of my friends have pointed out to me, we never actually see Big Freedia or Messy Mya in the video; we only hear their voices. The men bounce dancing are seen only from behind and often in shadow. There is a compelling interiority to the video — a lot of it specific to black people, Southern black people, people from New Orleans, and queer black people.

While it is impactful to have queer voices and bodies present in an imagining of black resistance, could it perhaps be more impactful to unveil them? I believe this video is one of the most important artistic contributions to the discourse on black resistance by a mainstream artist in recent history. Even still, it could do more. That being said, this is only the first song and video after Beyoncé’s year-long hiatus. I’m excited to see what’s to come.