All images courtesy of Featherproof Books.

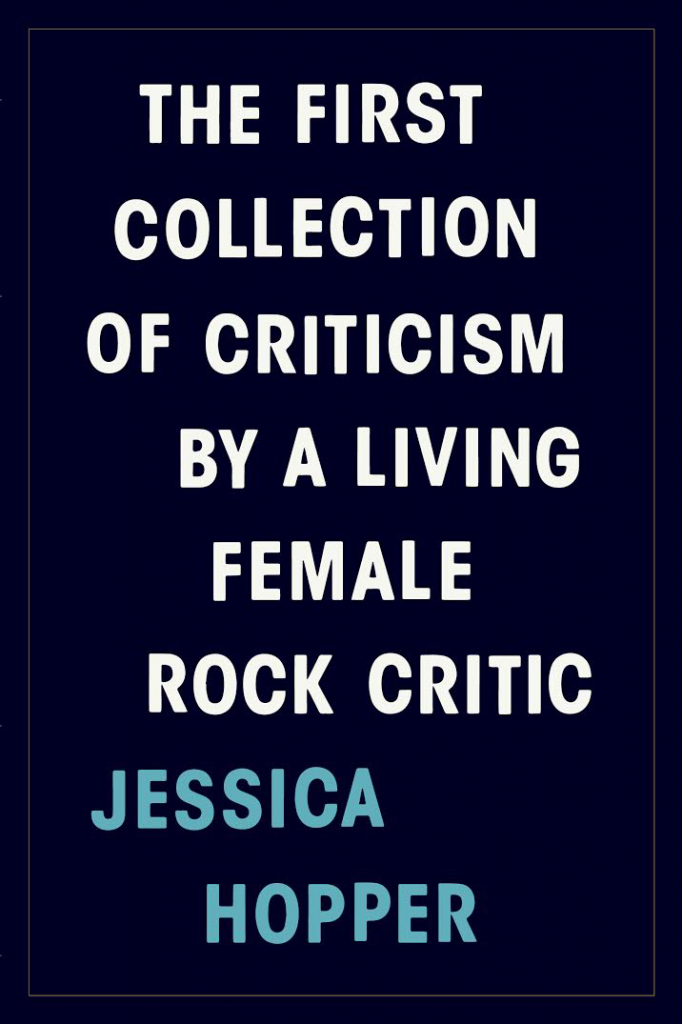

Jessica Hopper is a Chicago-based music journalist who’s written for publications like Rolling Stone, SPIN, and the Chicago Reader. She recently released The First Book of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic through Chicago’s own Featherproof Books. The collection itself is both poignant and full of razor-sharp wit. It’s also brimming with a genuine undercurrent of love for all aspects of the music industry. From writing about her own grunge phase as a teenager to profiling Annie Clark (St. Vincent), Hopper shows us how worthwhile it can be to cultivate a passionate and critical eye towards the music industry. We sat down over Skype to talk about everything from Grimes to Miley Cyrus and our mutual gratitude towards riot grrrl.

Rosie Accola: Since you write from the perspective of a fan, do you have a record that just kills you every time you listen to it?

Jessica Hopper: I mean, I have a few. … Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks is probably the primary one. … There are a lot.

RA: Why do you think journalists subject female musicians to “gotcha feminism,” i.e. asking if they’re a feminist without a clear understanding of the underlying connotations of the word?

JH: I think we don’t consider women’s work or knowledge to be authentic, and that women are not necessarily viewed as authorities on their own experience, per se.

RA: What’s the most difficult part of writing about music for a living?

JH: It used to be just making a living out of it. Now that I’m at Pitchfork full-time, the primary part is you never have as much time to write. There’s so much work that I want to do in the world, books that I want to write. As a mom, as someone’s who’s employed full-time, as someone who has other books coming … there are only so many hours, and that’s probably the hardest part.

RA: Especially since music is something that’s so … vast.

JH: I think it’s also that you want to be on top of it out of your own intellectual curiosity. But also you want to, as a writer, participate in culture and have certain kinds of conversations.

RA: You started writing in zine and self publishing formats. What is it about zines that resonates with you?

JH: Back then that was the only medium. I started writing twenty years ago, when there wasn’t an Internet to publish on. I mean, there was, but it certainly wasn’t accessible to me. I knew a lot of people who did zines, and if you were writing for yourself, that’s what you did. Also that was one of the primary ways to participate in music if you weren’t a musician, or even if you were. Zines were the format, particularly within punk rock and underground scenes, that was it. There was no mass media.

RA: With events like Chicago Zinefest and bookstores like Quimby’s, is it cool for you to see that zines are still part of the cultural discourse, even with the Internet?

JH: Yeah, very much so. I still have a fair amount of friends who do comic books, and we see that comics is incredibly strong. I don’t know a lot of people who do zines habitually but it’s still very much an expression of fandoms.

RA: You said, “writing about Miley [Cyrus] is simple because she’s impossible to define yet easy to vilify.” Do you think the weird sort of Miley vilification is symptomatic of our desire as a culture to victimize young female artists the minute they make a mistake?

JH: Absolutely. It’s like young women are some of the ones who tend to make us most irate because they seem to care the least about what the world wants or expects from them. So, in that way I think they become dangerous to us as a culture. I think that’s what people think … not that’s actually what they become. Also because … I’m paraphrasing Lacan here, there’s sort of a vastness to womanhood and young womanhood. It’s that women cannot be defined. Or women are infinite, and men are finite. I think sometimes the vastness and freedom associated with young women makes it seem like young women are sort of living out of bounds, so that becomes something that we demonize. I think demonize more than victimize.

RA.: Especially within rock ‘n’ roll, young female rock musicians are sort of constantly criticized. It’s such a weird dichotomy. It seems like fans crave intimacy and authenticity with these musicians (fixations with Twitter or Instagram), yet those same fans are also quick to abandon the artists at the first hint of a scandal or anything that’s raw or messy or human. What is it about being a musician that seems to obliterate the line between true and false?

JH: Maybe this is sort of a sideways answer, but I think that social media has given us a sense of ownership that we don’t have. It goes from being “this is my band. I’m the #1 fan. I’m the great understander,” and it goes into this sense of ownership. We see that with Kanye, we see that with other people. Everything from One Direction on down, people want to have these connections through social media and to exploit them.

This certainly happens for me. I don’t follow a lot of musicians on Twitter because I find that it turns me off from people’s music, like, 80 percent of the time … or that it can. It’s just, like, T.M.I, like, “Oh, you’re actually an asshole.”

RA: Do you think that the performative aspects of femininity also play into how female musicians are viewed by the media?

JH: Yeah of course. That was actually what my next book was going to be about, and instead I put all that stuff in this book. That’s all the “Real/Fake” chapter is about. I think it’s not just about the performance of femininity; it’s about acceptable femininity. Ultimately the thing that outrages people, when you really get down to it, is ambition. How do people square with ambition? You know, Grimes, how people have treated her since she did the song Go.

RA: Oh my God I know, it makes me so mad. People will say that she scrapped the song because of “fan outrage,” but she’ll go on her blog and be like, “No it’s because I was depressed when I was writing it.” It just infuriates me to this subhuman level where nothing coherent comes out and I’m just like, “Be nice to Grimes!”

JH.: I really think that she is someone who’s sort of taken down whatever wall is normally there. She’s offered a lot of people very real-time reactions to what happens to her as an artist and about her feelings about things, which is really very interesting. You look at someone like Bjork saying that she put up with stuff for years because she didn’t want to say anything about it.

It says something about music right now and music culture when Grimes is like, “No, I want to say something about this. I want to call this out on Tumblr.” She’s part of that different generation that views that differently, and maybe that’s because they might see the futility in it.

RA: You experiment with different journalistic formats. Your oral history of Hole’s Live Through This was great. How do you decide on a format for a specific piece?

JH.: Normally it’s dictated by the assignment. It depends on how I want to come at something. I didn’t pitch features a lot because I’m more interested in doing criticism, and it kind of doesn’t matter what the artist thinks about what went into the album. There are certain things where I think having that dialogue, like in my feature about Annie Clark towards the end of the book, feels really good. I felt like I had a different perspective from all the other people who were covering them. Maybe I was incensed because they were being presented in a particular light. I really wanted to make sure that there was some sort of corrective, a feminist corrective sometimes, because it is valuable. I’ve understood that lots of times that was something I could offer, that my perspective was of value.

RA: I think so much of journalism is viewing culture critically and seeing that absence of criticality and wanting to fill it.

JH: Absolutely. That’s like the entire reason why I started writing about bands. I felt like the bands that I loved were fairly misunderstood, if they were covered at all.

RA: Do you find it difficult to combine the journalistic aspects of writing with the personal?

JH: I don’t think I struggle in that way. It just reveals a different kind of criticism. Sometimes I don’t have a lot of interest in writing about what I love because my understanding is more visceral than what I’m getting out of it as a critic.

RA: Let’s talk about teenage-hood. You write for Rookie. That website debuted the first day I started high school, and it’s got a pretty solid place in my heart.

JH: It was very fun. I really love working in a community of such creative and ambitious people. It was a chance to constantly learn about different perspectives and ideas. I don’t think I’ve ever been part of another community that was so supportive and pro one’s existence. There was always a lot of solidarity with one another. I’m really glad to see some of the people who came out of Rookie getting book deals and going on to other things and to see their work bringing people back to Rookie.

RA: I was born in ‘96, but Bikini Kill was so important to me when I was in high school. Do you think there’s something about riot grrrl that continues to resonate with teen girls in underground or DIY spaces?

JH: I think the message of riot grrrl was basically permission to live, permission to resist. A different kind of archetype of empowered self, that there were people in the world who really looked at teenage girls as valid. That was very much what it was for me and that continues to underscore how I work today. I really see the value in relationship to young women, and struggles I encounter as a woman in a male-dominated industry at almost 40. I look at them through these sort of riot grrrl lenses. It still helps me sort things out because the fundamental truth of my life has now been underscored by those ideas for 20 years. It’s allowed me to build careers and connections and self-esteem on top of that.

RA: It gives you this whole little tool belt for dealing with bullshit. People will say that sexism in the literature industry is over because there’s a female editor at a publishing house, but it’s not over.

JH: Yeah, we get told in Bikini Kill #2 that “one of the ways that people will try and tell you that sexism doesn’t exist is by passing it off.” There will always be men telling us that the world we see is not truly the world we see. But, what riot grrrl told me was that my understanding was as expert as anybody else’s, and I continue to operate from that place.

RA: Especially with younger teenage girls, there’s so much second guessing of their authority by the media. The media’s so quick to dismiss artists who are marketed towards teenage girls as not important. People think Taylor Swift dates a lot of guys so she can write songs about it, when it’s like, no … she’s an entity at this point.

JH: It’s sort of like that Joni Mitchell quote although not exactly applicable to Taylor Swift. She’s got a “Joni problem.” Joni Mitchell said that whatever man was in the room got credited for her genius, and it’s like we might not be crediting these men for her genius but we’re crediting them for being her muse. I think she’s much more savvy than anyone has long given her credit despite the fact that at age 16 she was breaking Elvis’ record for simultaneously churning out albums and pop hits. She did that herself.