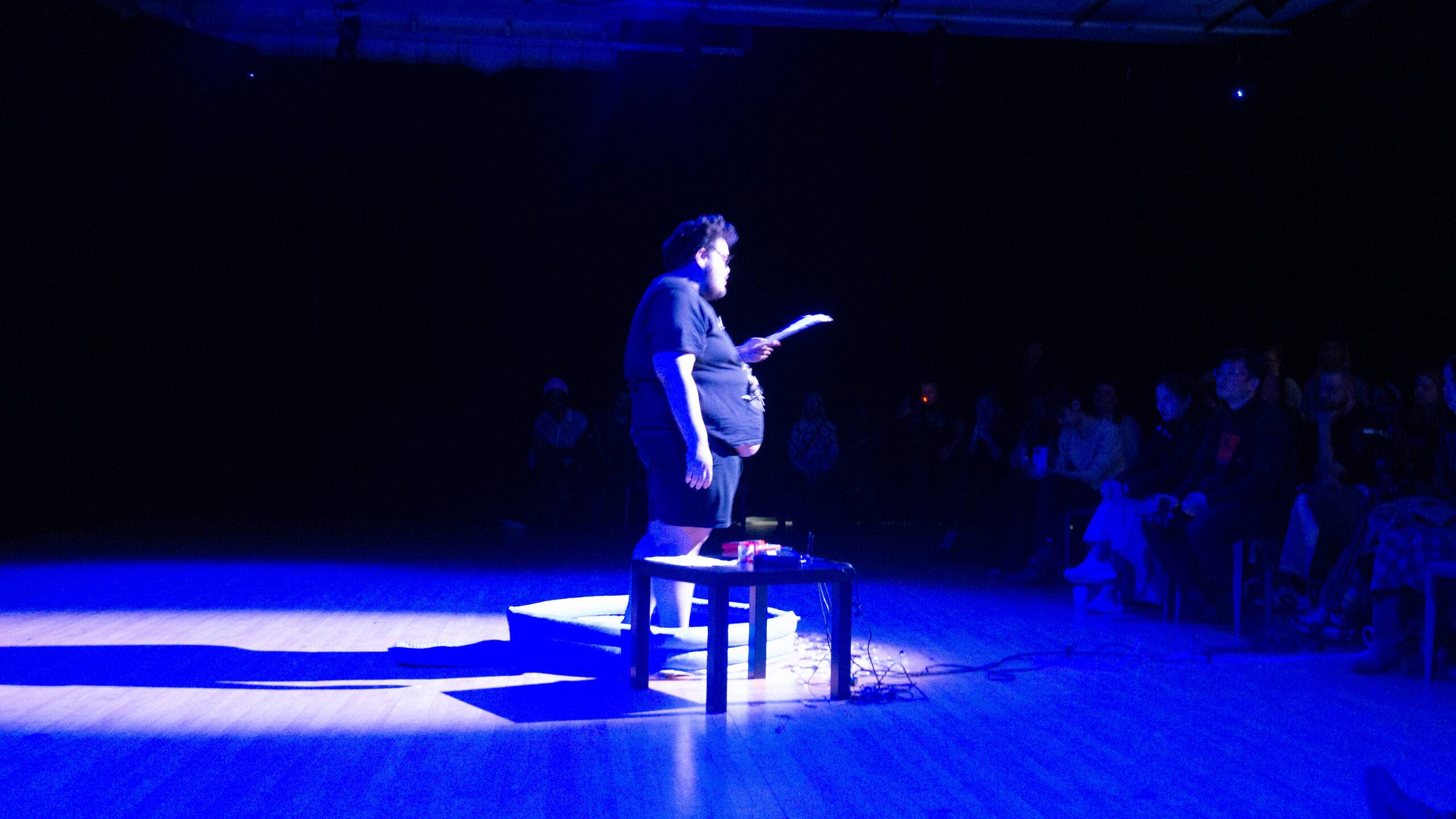

John Judd in Steppenwolf Theatre Company’s production of “Clybourne Park” by Bruce Norris,directed by ensemble member Amy Morton. Photo by Michael Brosilow.

Admittedly intimidated by Shakespeare, and hoping to one day interpret Willy Loman in “Death of the Salesman” or George in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” John Judd, is a self-taught actor and SAIC alum who has conquered the local and national theater scene and is currently playing two roles in “Clybourne Park” at Steppenwolf Theatre.

Alejandra González Romo: You studied painting at SAIC (from 1979-1981). How did you jump to acting?

John Judd: My paintings got more and more narrative. I think they wanted to be stories instead of paintings. I asked myself, “What if I did that?” It was the scariest thing I could think to do. I had to investigate it, though. It was a little experiment that took over my life. I started doing improvisation in 1985. I was 30, so I was kind of late. If I had lived in New York, I wouldn’t have been able to come in through the back door like I did here. I’m the luckiest guy I’ve ever talked to.

AGR: What did you find in theater that you didn’t find in painting?

JJ: I didn’t like the detachment of working on objects and having them be alone in the world. I always wanted to be in the room with them. To make myself the delivery system was a better fit for me. When I started acting I didn’t really care if it was art anymore. Going to art school, I became obsessed with that. I worried if my work was significant, meaningful or important; all those words that they use in art school. Acting, I had a direct effect on an audience. For me, that was completing the transaction and I didn’t have to worry about how to call it. That was a big relief for me.

AGR: Looking at your previous plays I found many socially critical stories that deal with racism, hypocrisy and avoiding calling things by their name. Do you think those aspects of our society have changed since the years of “Othello,” or “Crime and Punishment” into our day, as we see in “Clybourne Park?”

JJ: If you can take a play that was written in the 16th century and do it in in the 20th century and it’s still relevant, obviously, some of the same things are still going on. The things that good plays are about are universal and will always be with us: conflict, life death, love. The things that motivate people to do what they do don’t essentially change. We are not perfect, we are not an ideal society.

AGR: You’ve made self-conscious plays like “Orson’s Shadow,” where you played the famous actor, Laurence Olivier. This story is critical of your own profession. What was that experience like?

JJ: To play Laurence Olivier was an outrageous thing to be asked to do. It was very intimidating for me. It was very difficult to walk around in that character, and I still feel haunted by him a little bit when I see him in a movie. I studied him so carefully and I feel like I got inside of him somehow, even though he was long dead before I got to play him. It is a very weird thing that can only happen in my job. To develop that kinship with a person I never met. It was a fantastic, exhausting and exhilarating experience that left a really strong impression in me.

AGR: You have also done some work for film and television. What is special about theater?

JJ: I read once in The New York Times that the careers where you get the most adrenaline in your blood stream are one, test pilots, and two, stage acting. You have to be louder and larger in order to do live theatre. For me, that thrill is preferable. I don’t think I can live without it.

AGR: What is your main challenge as an artist?

JJ: It doesn’t get easier. The possibility of failure is always present. An actor should never get comfortable. It is not interesting to watch a person be comfortable. You have to strive for what keeps you on the edge. To me this is all kind of a gift — I came to this slate, and now that I am 25 years into it, it’s still a treat. It still feels like getting away with something.

AGR: What is the best thing about your job?

JJ: I get to play. My favorite thing about it is when we first start rehearsing for a new play and we come into a full room, where everyone comes at it from a different direction, but towards a common goal. I have a friend that says that is when the art happens, and after that, it becomes a commodity that you have to sell eight times a week. It is sort of true.

The end of each performance is an affirmation. It is a formal ritual when we drop the pretense, drop the fiction and walk out as who we really are. It is a little ritual of acknowledgment — it’s wonderful. I love that moment when the lights come up and we see each other face to face as nothing more than people.

It’s great — it’s like medicine.

Clybourne Park, Sept. 8—Nov. 6

Steppenwolf Theatre