Steven Spielberg is the director I have seen the most films from. I wouldn’t say any of those are in my list of favorites, nor do I dislike any of them, though I was horribly bored by “Lincoln.” I like plenty of his movies, but I didn’t realize how many of them I had seen until I stopped to count. I’m going to go out on a limb and guess it might be the same for you too, not because I believe you to be a Spielberg fanatic but because I suspect you’ve watched some movies, and Spielberg has made many. 32 to be precise, across genres. There’s history with “Lincoln,” outer space with “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” musicals with “West Side Story,” horror with “Poltergeist,” though his credits on that one are subject for debate, war movies with “Saving Private Ryan,” and even reference-filled schlock with “Ready Player One.”

And besides all that, the man practically invented the blockbuster. “Jurassic Park,” “Indiana Jones,” “Jaws.” Speilberg loves telling stories of all sorts, and whether you’ve seen any or not, though you probably have, there is no doubt that the man influenced film as we know it in the modern era.

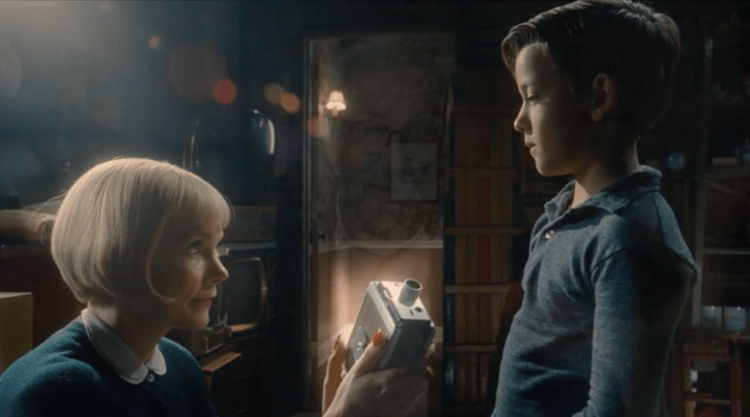

In his newest film, “The Fablemans,” Spielberg turns inwards, looking at the things that influenced him, and sent him to the camera and what made him stay behind it. It follows Sam Fabelman, a stand-in for Spielberg, and his family as they move across the country, and Sam learns to love the camera. The film has been touted as Spielberg’s love letter to cinema, a tribute to the medium that shaped him and that in turn, he shaped back. That makes it sound grand, like an intellectual statement, an abstract dedication to an entire medium, instead of what it really is: an intensely personal film, not just about art but also about Spielberg’s family.

It’s about those two halves of his identity, and how those two halves orbit around one another, always at risk of collision. The two are in diametric opposition, according to Sam’s Uncle Boris, doomed to tear each other apart.

It’s a cynical take from a grieving circus performer, and struck me as profoundly un-Spielbergian. Time and time again, Spielberg has shown us through the camera that he loves this more than anything. The moment had me wondering whether this was Spielberg’s cry for help, him tortured beneath his black baseball cap, behind the lens.

But as Sam learns, almost through opposition to his uncle, the art may precisely be how we show each other, and our families, love.

Heading the Fabelman household is Burt Fabelman, played by Paul Dano, a rising computer scientist and engineer dedicated to making physical things, and Mitzi Fabelman, Sam’s mother played by Michelle Williams, a gifted pianist, much more ethereal in her inclinations than Sam’s grounded father. There lies another set of opposites in the film; Burt, driven by reason and Mitzi, inspired by feeling, both of them viewing Sam’s burgeoning filmmaking practice differently. Burt sees it as a distracting hobby, while Mitzi sees it as a passion she has now lost. But Sam cares not. He keeps making his movies.

First, it is to fight his fears of the first film he saw, “The Greatest Show On Earth,” recreating the staged train wreck that scared him. Then it is to explore, to pursue his imagination. Then it becomes an exercise to see how far he can go with his handheld camera and strips of film. The form pushes Sam onwards, both a barrier between him and the world and his gateway to understanding it.

Being a film about filmmaking, Spielberg is welcoming scrutiny. But as is usually the case with Spielberg, the film’s cinematography is effortless. The film flows from one scene to the next seamlessly, every shot framed perfectly, the eye never uncertain where to look. This is especially fascinating when we watch Sam’s amateur films. Here, Spielberg takes it one step further: we’re seeing his perspective of Sam’s perspective, reflected twice over through the lens. Spielberg is letting us into his childhood’s perspective the best way he knows how.

There’s an ongoing dialogue between the superficial and the real in the film. Sam is shown to possess a knack for crafting practical effects, using his limited tools to recreate the flash of a gunshot, the dust flying as shells explode, the rupture of a bullet wound. It’s especially delightful to see Sam stumble onto these ideas in our digital CGI enhanced era. For that same reason, there’s a joy in how tactile Sam’s filmmaking process is: reels are snipped, glued, wound, before spinning on the projector in his closet. What Sam is doing is real, it’s physical, despite his father’s beliefs to the contrary. Like the film’s depiction of special effects, it is a reminder of the current state of film with almost all directors working digitally. There’s nothing snobby about it; Spielberg doesn’t place them on a hierarchy. He’s simply presenting to us the beauty of how he learned to handle the camera, not a love letter to all of cinema, but to the cinema he learned to make.

That line between the truth and lies gets blurred as the film goes on: Are Sam’s films true? What does he process through the moving image? What does he hide through the camera? That same division applies to his parents, especially his mother. Michelle Williams occupies Mitzi with capriciousness, flitting between elation and despondence. She wears a bright smile, but ever so often, her eyes reveal her sadness. Williams knows how to tow the line between real glee and a performed one, though at times, perhaps her performance is too large to feel real. Dano as Burt on the other hand, is subdued and stoic, until he can’t contain himself, playing the character with a surprising tenderness in possibly the most normal role of his career. Dano doesn’t fall into stereotypes of the punishing father, demanding Sam follow in his footsteps. It’s far more nuanced, we can see how he and Mitzi both express their love as they know how, though it is often at odds with what Sam thinks he needs. It’s again the same even-handedness we see elsewhere in the film; Spielberg does not condemn Sam’s parents, in fact he has great empathy for them, portraying them with a gentleness and forgiveness that must have taken a lifetime to build.

As I’ve said, “The Fabelmans” is immensely personal. And for that reason, it may strike some as indulgent, as Spielberg’s self-absorbed portrait of his own childhood. But for me, that’s precisely why it works. It’s detailed and joyful and heartbreaking because it is his story. It is about art, and family, and love, and heartbreak, and disappointment, and how all of those things made him into the filmmaker he is today. It’s executed with style, finesse, and most importantly, love. Because as cheesy as it may sound, when I walked out of that cinema, I felt the love Spielberg had infused into the film. It passed from his eye, through the lens, into the film, past the editing room, into a projector, and eventually to me. And if that isn’t what the movies are all about, I don’t know what is.

Myle Yan Tay (MFAW 2023) cares a lot about movies and comic books. One day, maybe they will care about him. Find more of his writing at www.myleyantay.com.