An American Communist and a Russian capitalist get on a boat. Somewhere out there, this is a dad joke waiting to be told, but until then, it is simply one of the many hilarities that occurs in Ruben Östlund’s second Palme d’Or-winning film, “Triangle of Sadness.” Five years after thoroughly lampooning the fine art world in “The Square,” Sweden’s enfant terrible of arthouse satire has decided to focus his incisive eye on a most daunting topic — social strata and the class divide.

Despite what early film festival review quotes may tell you, this is not a film about privilege. Privilege is something that we all have in some amount — one can be underprivileged but never completely un-privileged. Power, on the other hand, is what allows for the exercise of that privilege, and it is this aspect of power that “Triangle of Sadness” concerns itself with. Power, and how once we’ve tasted it, we’ll do anything to keep hold of it.

Östlund’s premise is deceptively simple. A materialistic fashion model couple go on a lavish spon-con cruise, where the haves — arms dealers, socialites, and a particularly lecherous Russian fertilizer magnate and self-proclaimed “shit-seller” — mingle with the have-nots — the yacht’s cleaners, crew, and radically unhinged Captain Thomas (played cheekily by Woody Harrelson in top form). It’s all fun and games at first. We giggle at the eccentricities of the elderly rich fuddy-duddies and feel pangs of sympathy for the service staff, who are put upon and performatively inconvenienced in the name of assuaging the boredom and guilt of their wealthy charges.

But then, in classic “Lord of the Flies” fashion, it all goes wrong in a spectacularly bizarre series of events that are as hysterically funny as they are revolting. (This is no exaggeration; commemorative vomit bags were distributed at the film’s US premieres). Thomas and the Russian “shit-seller” drunkenly quarrel over the intercom as the ship sinks in an explosion of sewage, and when the smoke clears, a small group of survivors find that the societal hierarchies they are used to no longer apply. But a power vacuum is never left unfilled for long, and no one — not even the most ardent revolutionary — is immune to the siren song of corruption.

In a decade that is already full of films about metaphorically and sometimes literally eating the rich, “Triangle of Sadness” sets itself apart from its ilk by actually forcing its (presumably mostly left-leaning) audience to challenge and question the extent of their beliefs. When drunken Marxist Thomas insists on hosting dinner on the one evening with a severe storm scheduled, is he a working-class hero for ensuring that almost an entire ship full of rich capitalists end up dead in their own vomit, or is he an overzealous revolutionary with no regard for human dignity? And when cleaning lady Abigail, the only one who knows how to catch fish and stoke a fire, takes charge of the desert island stragglers with an iron fist, how far is she entitled to go with her newfound power? When she coerces rich young model Carl into having sex with her in exchange for regular food supplies, do we clap and laugh and say, “Good for her!” Or do we raise an eyebrow and chuckle uncomfortably in our seats? When the abused ultimately become the abusers, is it vengeance, victory, or tragedy?

“Triangle of Sadness” is rife with dilemmas like these, some of which reside within its characters too. Lead actors Harris Dickinson and the late (and great) Charlbi Dean embody their oft-vapid but nonetheless likable model-influencer couple Carl and Yaya with great poignancy and pathos. Carl, despite his cookie-cutter good looks, is a man living on the edge of emasculation; nothing but a stepping stone to sex, social clout, and free food for the women in his life. On the flipside, Yaya is only as cold and manipulative as she is due to her own hyperawareness of how she is perceived within our ever-misogynistic society — she may make three times as much money as Carl, but as she says, “the only way out [of her modeling career] is to become a trophy wife.”

Carl and Yaya’s relationship is a game where the goalposts are always moving, and yet, to Östlund’s credit, he manages to pepper their misery with genuine glimpses of joy. But we are still never quite allowed to forget that their subversion of gender norms doesn’t absolve them from the ever-present issue of social strata and power. A lavish dinner date ends in an argument about money. A night of passion is only made possible by role-playing as poorer people. They are as much victims of the system as they are its perpetrators, and Östlund’s off-kilter brand of satire shines the brightest when the narrative turns to them.

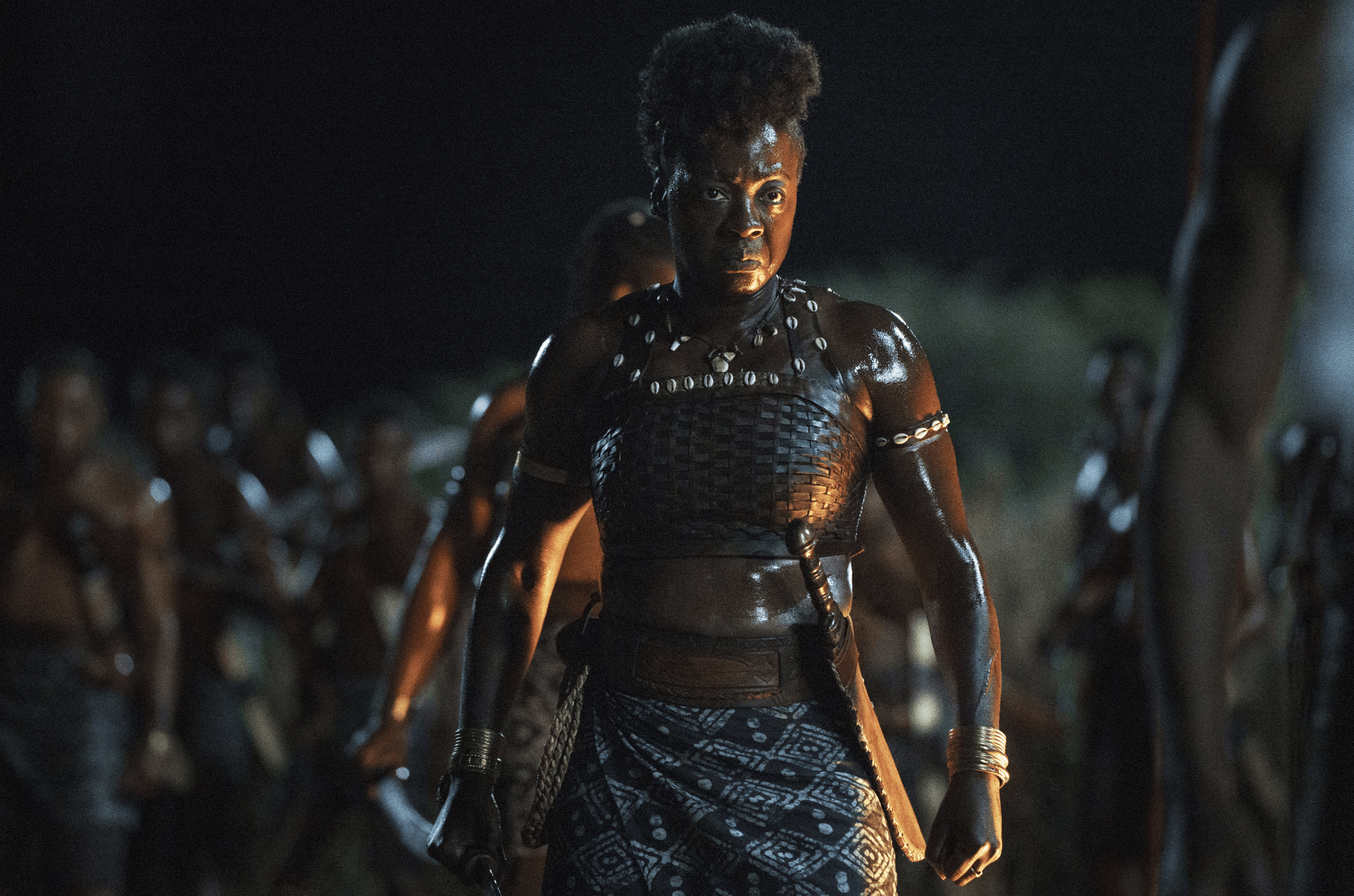

However, performance-wise, the highlight of “Triangle of Sadness” is undoubtedly Dolly de Leon’s stellar turn as cleaner-turned-dictator Abigail. While the first half of the movie is driven by slapstick Surrealism, the second half hinges almost entirely on de Leon’s charisma and, towards the end, her visceral expressiveness. Her final scenes are so arresting they could topple a world order, and while the film ends a little too abruptly for audiences to see if that truly comes to pass, one is inclined to believe it does.

Walt Whitman’s oft-parroted quote could not ring truer today: “We all contain multitudes.” In the face of endless complexity and an increasingly entrenched and exploitative capitalist world order, holding fast to a fixed ideology isn’t the only thing that will save us. There is nuance in everything. “Triangle of Sadness” knows this best, and is determined to laugh in the face of an increasingly unjust and unpredictable world. You’ll laugh. You’ll cry. Maybe you’ll projectile vomit. But you’ll definitely have a good time. Just make sure you keep a paper bag on hand.

Nestor Kok (MFA VCD 2022) is an SAIC and F News alumnus turned graphic designer by day and entertainment features writer by night. He has been described as “Timothée-Chalamet-adjacent” … whatever that means.

NESTORRRRRRR