A Human Position

dir. Anders Emblem (Norway)

U.S. Premiere

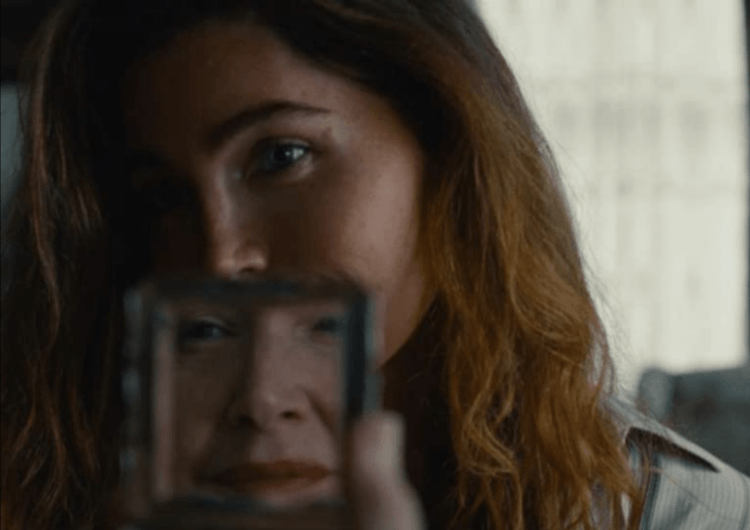

This quiet, minimalistic drama revolves around Asta (Amalie Ibsen Jensen), a young journalist based in the sleepy seaside town of Ålesund, Norway. Returning to work after recovering from an unnamed (but implicitly sexual) trauma, she quickly grows weary of covering inconsequential small-town happenings, but is soon reinvigorated when the story of a local asylum-seeker facing deportation reaches her.

“A Human Position” is undoubtedly a beautiful watch, with Michael Mark Lanham’s carefully-crafted cinematography giving new meaning to the phrase “every frame a painting.” But these shots often linger for longer than necessary, and mostly feature Asta wandering nowhere in particular, with a permanently pained expression on her face like a Norwegian “Midsommar”-era Florence Pugh. Where these artistic choices truly shine are when exploring Asta’s loving but strained relationship with her girlfriend, Live (the outstanding Maria Agwumaro). The slow recovery of their love through soft-spoken, intimate scenes serve as brief, much-needed moments of delight in a vast abyss of small-town malaise and unfulfilled ambition.

However, the central thrust of the film’s narrative itself is left severely lacking. While “A Human Position” could arguably work as a slow, understated meditation on the lost and departed, we never see the asylum-seeker Asta is desperately chasing, nor do we get any real resolution to his story. Emblem’s script deftly portrays the many hang-ups and complications of European governmental bureaucracy, especially when it comes to immigrants and refugees, but the ethics of centering an underprivileged immigrant in the narrative while only ever featuring a white woman peripherally telling his story are also rather questionable. One would be hard-pressed to feel truly satisfied by the time the film’s meager 79 minutes are up, as all we are left with are isolated moments of beauty that mean nothing of real consequence.

Leonor Will Never Die (“Ang Pagbabalik Ng Kwago”)

dir. Martika Ramirez Escobar (Philippines)

This year’s film festival circuit will probably not see a more earnest, heartfelt entry than “Leonor Will Never Die.” As poignant as it is chaotic, Martika Ramirez Escobar’s genre-bending film throws camp, over-the-top 80’s action pastiche, and deft metafictional explorations of grief into a supercollider, letting it all rip over the course of an increasingly surreal 100-minute runtime.

Leonor Reyes, a retired writer and director of gonzo gangster flicks, spends her twilight years absent-mindedly cooking, buying pirated DVDs off the streets, and forgetting to do anything remotely important like paying her electricity bills. Leonor is also a woman haunted; constantly shadowed by both the wasted promise of her unfinished script “Ang Pagbabalik Ng Kwago” (The Return of Kwago), and the literal ghost of its main character Ronwaldo. When a television set falls on her head and sends her into a coma, she is transported into her own script and must complete it to awaken, while her estranged husband and recalcitrant son do all they can to keep her alive in the real world.

The film’s best moments lie in its technical choices — manual zooms, oversaturated colors, cheesy synth soundtrack, and exaggerated yet whip-smart choreography that hark back to the stylistic look and feel of 80s South East Asian cinema without uncharitably cheapening a bygone age. While the first act stumbles a few times in terms of narrative clarity, the second act finds sure footing, and culminates in a “Truman Show”-esque final act that spirals into magical, metatextual chaos and comedy. Escobar makes some very daring directorial choices, pushing the envelope on breaking the fourth wall — one could argue that it even breaks a fifth wall that most other directors didn’t even know existed. “Leonor Will Never Die” also achieves the perfect balance between tragedy and comedy, deftly ensuring that moments of grief and mourning have enough room to strike a chord in viewers’ hearts, before returning to the slapdash chaos of its unique brand of meta-humor.

It’s impossible not to be beaming by the time the film’s joyful, musical outro unspools onscreen — a love letter to 80s Filipino cinema, the process of filmmaking, and most of all, the hard work of the film’s cast and crew. “Leonor Will Never Die” is a truly delightful cinematic outing; one that its creators clearly enjoyed crafting, and that its viewers will, likewise, enjoy seeing.

“Leonor Will Never Die” opens in select U.S. cinemas on November 25, 2022.

Monica

dir. Andrea Pallaoro (USA, Italy)

North American premiere

Both a meditation on transgender identity from a refreshing new angle and a showcase of strongly compelling performances from its main cast, “Monica” is a welcome addition to modern art-house transgender film canon, alongside films such as Sebastián Lelio’s “A Fantastic Woman” and Rajko Grlić’s “The Constitution.”

The titular Monica (played by a stoic yet graceful Trace Lysette) is a woman on the verge in Los Angeles. She lives a mostly solitary life, fending off aggressive cat-calls from strangers and leaving tearful, groveling voicemails to her ex-boyfriend. But a call from her sister-in-law Laura (Emily Browning) sends her back to her childhood home in exurban Ohio, to take care of Eugenia (veteran actor Patricia Clarkson in top form), her terminally ill mother who rejected her more than a decade ago. Unable — or unwilling — to face her mother as herself, Monica poses as a hospice nurse instead, starting down a path to reconciliation, forgiveness, and oft-unspoken acceptance.

In “Monica,” Pallaoro and co-writer Orlando Tirado explore trans identity and its effects on familial relationships without the usual emotional torture porn that most filmmakers think is requisite for discussing such themes. That isn’t to say that everything is peachy keen from start to finish, though. Every exchange between Monica and her family is loaded with subtext that viewers must interpret themselves, charitably or otherwise. When Monica tells her brother Paul that his son resembles him closely, Paul replies, “He reminds me more of you, actually.” There are also constant remarks made about how Monica is “unrecognizable” — and given the context of her family being born and bred middle-class Midwestern stock, we’re inclined to believe these aren’t exactly compliments.

Even when she is alone, the universe seems to conspire against her. After a date gone wrong and a heated argument with her brother, Monica gets into her car and drives away, only to grow tearful as Pulp’s “Common People” comes on the stereo — “You’ll never live like common people/You’ll never do what common people do.” And in some senses, this is true. Her journey with Eugenia towards the end of the latter’s life is much unlike anything most people go through, yet “Monica” shows us that forging your own path is sometimes the best thing that one can do, both for oneself and others — and one doesn’t need to be transgender to resonate with such a sentiment.

Patricia Clarkson could not have been a better choice to play dignified, ailing Eugenia — the subtleties of her performance will leave viewers in awe (and in question) at every turn. Does she know who Monica really is? What is the significance of her inviting Monica to be in a family photo? Has she accepted her daughter’s transition, yet remains too proud to apologize for the hurts of the past? Or is she merely forming a bond with a stranger tasked with caring for her in the vulnerable final moments of her life? We are left guessing in the end, but the tone that the film strikes elsewhere may leave us some hints, such as a scene in which Monica’s niece plays pretend midwife while her brother “gives birth” to a baby doll — showing us that the tides of trans acceptance are shifting, from generation to generation, for the better.