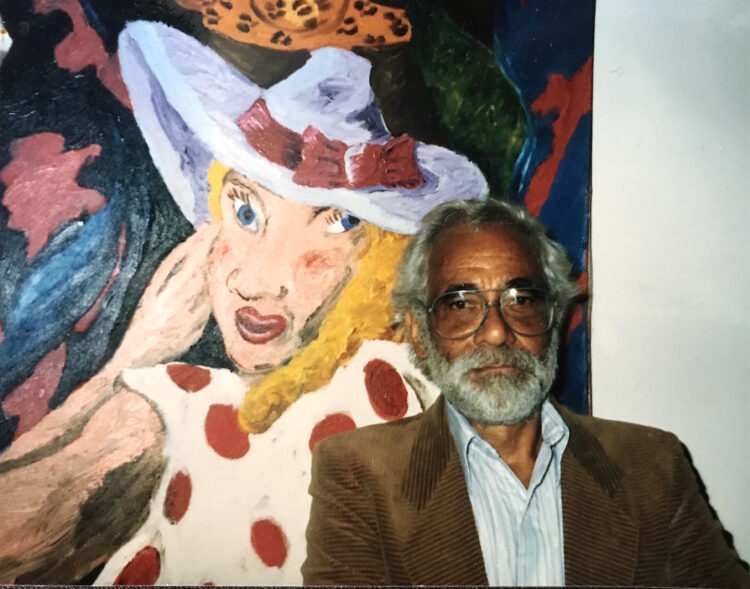

The Chicago Cultural Center’s vast retrospective of painter Robert Colescott (1925-2009) is, I think, defined by dualities. Caricature and portraiture, Black and white, high-brow and kitsch, original and iteration all come into play throughout the exhibition hall. His vivid spins on art’s history and race in America — often fusing Black caricatures with canonical art images — produce a bright show with a bleak sense of humor.

The exhibit charts Colescott’s diverse career, starting with his early work as a student (born and raised in Oakland, CA, he’d go on to train under painter Fernand Léger during a stint in France). We see his initial forays with post-Impressionist and Cubist modes, to his mature period and explorations of American culture, the latter of which makes up the bulk of the exhibition.

Long before artists like Kehinde Wiley and Titus Kaphar found acclaim in reimagining Western historical painting — Wiley’s recent pictorial response to Thomas Gainsborough’s “Blue Boy” comes to mind — Colescott probed painting’s past for launch pads of opportunity. References range from the canonical (a riff on Théodore Géricault’s 1818-1819 “Raft of the Medusa”) to the contemporary (a cheeky facsimile of a Roy Lichtenstein interior, who in turn produced his own spins on Picasso and Mondrian). The former is an extreme extrapolation of the original, now titled “The Wreckage of the Medusa” and featuring, well, a wreck. Colescott reduces the once-heroic crew of the once-complete ship into a set of amputated components adrift at sea. In this flotsam, it’s everyone for themself. One castaway leers towards a nearby woman while another throws a concerned glance towards an off-view threat — is the worst yet to come?

It’s impressive work — more impressive, I think, when Colescott leans on his own inspiration. One original highlight: “School Days,” a stuffed, imposing composition. Here Colescott ruminates on race, opportunity, and the law. Lady Liberty, shown here as a Black woman with an exposed and blindfolded skull, presides over the affair; her scales literally weigh a Black man against the value of a dollar. Behind her, a courthouse of green, red, and black nods to the colors of the Pan-African flag. In the left corner, a white woman graduates from the titular school with a diploma in hand. Meanwhile, the Black man next to her gets a gun. White woman finds opportunity, it seems, while Black man fights to survive, his value never assured. Colescott makes a point of turning the gun’s barrel directly on the viewer — is this a fourth wall-breaking accusation, a reminder that the real consequences of racial inequality lie not in the work, but in the real world?

One of Colescott’s strengths, I think, is his ability to neutralize the racist, Jim Crow-esque caricatures and to rob them of authority. “It’s the satire that kills the serpent, you know,” he once remarked. By injecting these figures into the annals of art history, as in his Lichtenstein riff, a kind of nullification takes place, as if to say “I see your canon, now what if I add this?” In other instances, such as the electric “GO WEST,” Colescott offers a more sympathetic spin. Here, the stylized figures are in fact Colescott’s parents, who moved from New Orleans to Oakland in the early 20th century. Enveloped in cotton candy clouds, the two gaze into each other’s eyes across a soft, quilt-like map of America. In the center, two birds in a nest raise a pair of hatchlings.

It’s a blessing and a curse that the responsibility of exhibiting Colescott falls upon the Cultural Center and not, perhaps, the bigger brother that is the Art Institute a few blocks down. Crowds seem to have rediscovered the AIC and flock in droves, while at the CCC the sound of wooden floorboards continue to audibly creak without disruption, and where Colescott’s work can be taken in without distraction. There is time and space to digest his work (and you will need it — they are meaty affairs).

“Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott” can be seen at the Chicago Cultural Center from now until May 29, 2022. Admission is free.

Pablo Nukaya-Petralia is the art editor for F Newsmagazine. Klaus Biesenbach once hit him with a cup of ice cream in front of Caroline Polachek, no cap.