Upon arriving on campus this August and September, all SAIC students, faculty and staff will begin the fall semester with a packet of five masks, their own personal thermometer, and a checklist of COVID-19 symptoms to help them monitor their health on a daily basis. They’ll also see plexiglass partitions, signage for how to socially distance in each lobby and classroom, staggered class schedules, and elevator capacities that cap off at four people, among other measures accompanying the school’s Make Ready plan.

The plan’s framework is guided by the advice of Dr. Terri Rebmann, Director of the Institute for Biosecurity at St. Louis University and a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the school’s College for Public Health and Social Justice. Dr. Rebmann holds a PhD in Nursing and is certified in infection control, and she will continue to guide SAIC’s administration in preventing the virus’s spread and responding to potential outbreaks through the upcoming semesters.

Colleges and universities around the country have been largely left to their own devices in determining how — and if — they will reopen their campuses. “There’s not currently a standardized approach to reopening so every university is making their own plans,” Dr. Rebmann told F Newsmagazine in a Freeradio SAIC interview on July 31.

Even though the school is offering optional “modified in-person” classes, The Chronicle of Higher Education places SAIC among the roughly 27 percent of colleges and universities nationwide that are holding classes primarily online, compared to 20 percent that are primarily in-person, 15 percent using a hybrid model, 6 percent that are fully online, and 2.5 percent that are fully in-person. These numbers fluctuate significantly between public and private schools: public colleges and universities seem to be leaning further towards plans that offer mostly online course options while private institutions are giving students more on-campus options.

SAIC’s designation within the “primarily online” category is based on the fact that it is only offering in-person classes for subjects that are considered exceptions to the capabilities of remote learning — labs and studio courses, for example. “Hybrid models,” on the other hand, leave the decision of whether or not to hold classes online up to individual professors, each of whom can alternate their decision on a weekly or daily basis.

And as far as what reopening decisions look like from campus to campus, Dr. Rebmann said that there is overlap in “the protective measures that are being used for campuses that are choosing to reopen.” As an example, she noted that every university that she has been in contact with is planning to do daily health screenings.

But where schools overlap depends on a handful of factors, including location, resources, and even the types of education and experience that each school offers. For example, Dr. Rebmann has emphasized SAIC’s lack of scientific resources, pointing out that without lab facilities, mass-testing isn’t an option for us. She has stated in webinars and in our interview that she doesn’t consider required entry testing to be an effective means of controlling the spread of the virus.

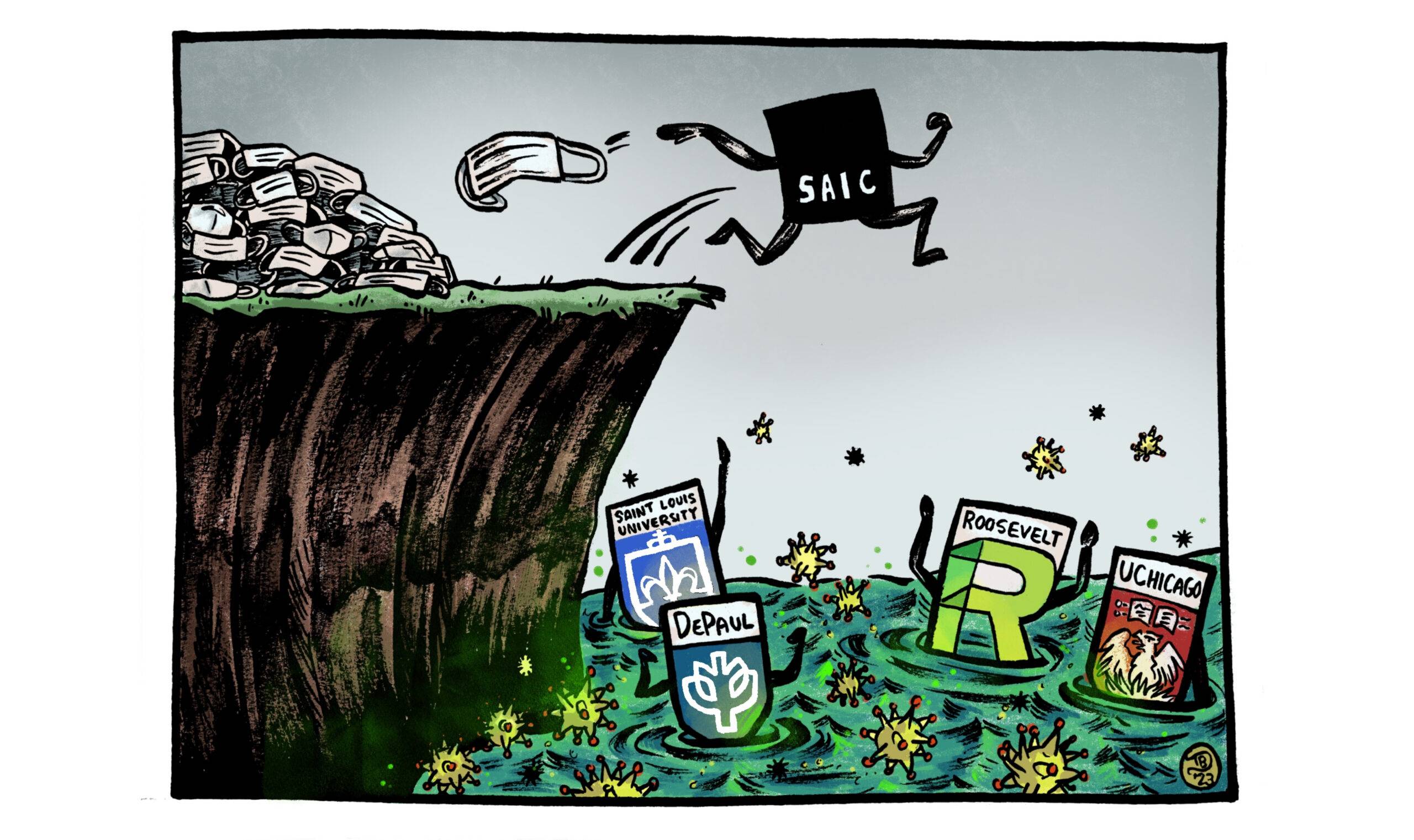

Though, if we look to Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), which is reopening with a hybrid model, there’s an obvious investment in resources to support off-campus testing instead: IIT is offering full reimbursement for entry testing fees to any student, faculty or staff member who uses Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance coverage — the same provider as SAIC — and they’re allowing staff and faculty to get tested during their regular work hours.

Along with IIT, University of Chicago will also reopen with a hybrid model. University of Chicago — whose labs and researchers are currently developing contributions to the creation of a vaccine for COVID-19 — is giving all professors the option to teach remotely or in-person. They will also conduct periodic testing of on-campus residents and offer tests to anyone within the university’s community who exhibits symptoms. Testing will be done through the University of Chicago School of Medicine.

Similarly, University of Illinois – Chicago (UIC) will offer saliva testing at three different locations on their campus. UIC began with mandatory tests for groups including on-campus residents, and students and staff involved in athletics or performing arts, and they’ve since expanded to offer voluntary testing to all students, staff and faculty.

American Academy of Art and East West University will offer fully in-person instruction on their campuses in Chicago, but both schools have enrollment numbers far below 500 students.

Pandemic aside, SAIC operates on a different model than neighboring colleges and universities; with studio arts instruction as its top priority, the majority of our most vital resources are communal, stagnant, and require hands-on experience. Of the 36 Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD) member schools in the U.S. and Canada, SAIC is among 10 other schools holding classes primarily online, including Pratt Institute, Lesley College of Art and Design, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Eight AICAD schools will host a fully online curriculum, including Parsons School of Design, University of the Arts, Maryland Institute College of Art, and both California College of the Arts and California Institute of the Arts. On the other end of the spectrum, two AICAD schools will operate fully in-person — Kansas City Art Institute and the Institute of Art and Design and New England College. Additionally, five AICAD schools will offer primarily in-person instruction, including the Art Academy of Cincinnati, Cranbrook Academy of the arts, and Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. Hybrid-model AICAD schools include Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Montserrat College of Art, and New York School of Interior Design.

But is the hands-on curriculum of art and design instruction an adequate reason to endanger not only ourselves but larger and more vulnerable communities of Chicago? SAIC’s Science Program Coordinator Kathryn Schaffer doesn’t think so. In response to SAIC’s Make Ready update on June 23, Schaffer internally distributed a letter outlining specific weak points in the plan. One of Schaffer’s arguments is the false reassurance that following state and federal guidelines offers. She wrote, “to say we’re following CDC and CDPH guidelines does not mean that we are safe. It more accurately means ‘the likely number of people who get sick or die is within the range considered acceptable to government.’”

In a July 15 Freeradio SAIC interview, Schaffer specified that it’s those beyond our student body who are most at risk by our return to campus, listing “the foodservice employees, the custodial staff, the people on the train, the people on the street corners, the people that students see in the rest of their lives, who they go home to.”

But Schaffer also added that, as a community of artists, educators, and intellectuals, we’re in a unique place to challenge these new norms of institutional response to crisis: “We have a lot of people who really think about ethics in a very serious way — also through their creative practice,” said Schaffer. “The government of this country has explicitly decided that the economy is worth lives. In all of the plans that they put forward about reopening schools make that assumption. But we can question that assumption and we should, because that’s the kind of thing that we do.”