This is the first of a series of notes. None of these were things I went to with the express purpose of writing about them, but then I found myself thinking about them, so I was already writing about them. I am interested in a fragmentary criticism, a criticism so dilated that it can no longer lay claim to authority and distance. Not long, transcendent looks at Art, but instead fleeting glimpses of living and visual culture: ads, websites, buildings, facades, potholes. This is a record of things I saw.

Elks National Memorial and Headquarters

I feel bad for the Elks National Memorial in the way I often feel bad for entities whose serious intentions (honoring the war dead) get scuttled by bizarre and melodramatic aesthetic choices.

The monument, built in 1926 by New York architect Egerton Swarthout, is an enormous dome of a building that faces Lincoln Park. It is a very distant and confused cousin of the Pantheon and more closely resembles a lemon juicer. Its resident strangeness derives from the fact that it looks like a smaller, more delicate pavilion that has been blown up to monumental size and translated into heavy stone.

“The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks” is a fraternal order with 2000 lodges across the U.S. It was founded in 1868 in New York City as a private social club by the Jolly Corks, a group of “entertainers,” so that its members could keep drinking after public taverns had to close. The official Elks website describes the Jolly Corks as “a group of actors and entertainers;” other sources describe them as minstrel show performers.

Although it is no longer an officially whites-only or men-only organization, discrimination cases have made headlines over the past several decades. There was the Annapolis Elks Lodge #622’s refusal to allow an 8-year-old African American boy to play a little league football team it was sponsoring; lodges from California to Norwich, New York have rejected the membership applications of their first prospective black members. These instances have been trailed by ACLU lawsuits, Department of Justice investigations, and also, sometimes, lodge members resigning in protest. (The Improved Benevolent Protective Order of the Elks of the World, or IBPOEW, was founded 1898 as a black fraternal order. Today it has 500,000 members in 1,500 lodges worldwide.) Elks can also be women now, or maybe it’s the other way around, that women can be Elks. In 1995, the Order passed a vote to allow women, although discrimination still exists.

It is therefore my preference to think of them not as Elks but as elks, picking solemnly out of early automobiles, hooves clacking up the dramatic stone steps to their giant lemon juicer of a building.

In fact, this conflation is employed by the Elks themselves in a number of images: an enormous painting of an elk with its chest puffed out in pride, looking out over a valley, like that Caspar David Friedrich painting, but with an elk instead of a man. The elk was chosen because it symbolized nobility. In the insignia, it stands in front of a clock face whose hands point to the 11, which is the hour when they commemorate their fallen brothers.

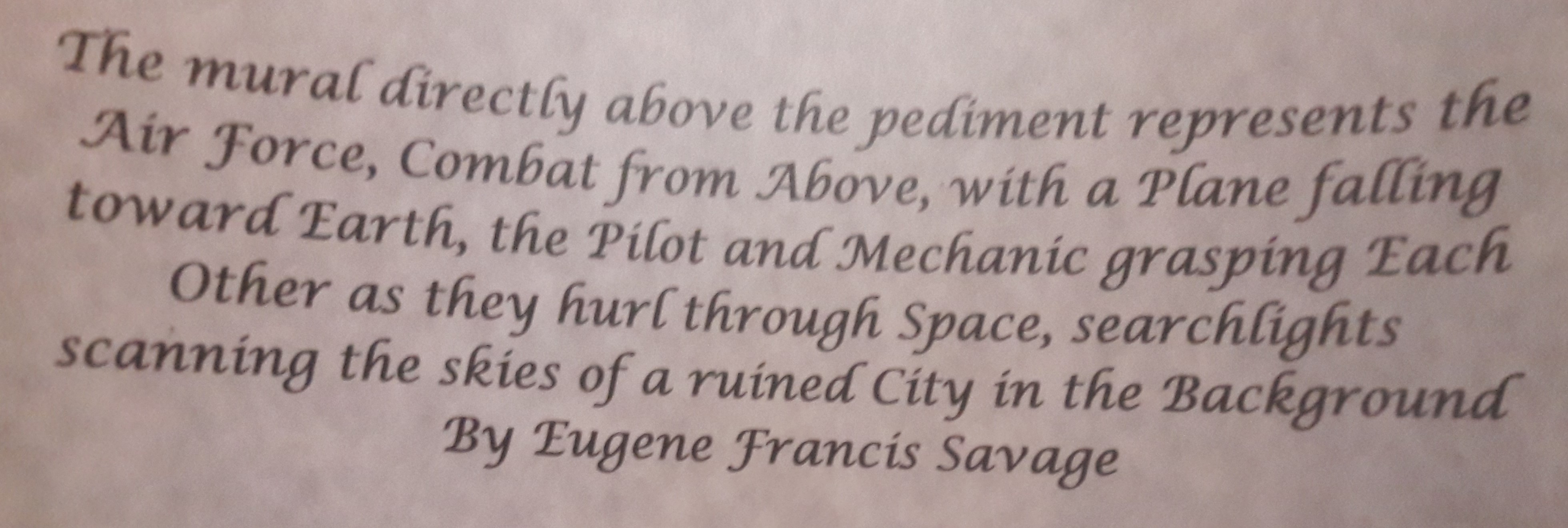

Inside the memorial, a cavernous, domed space, ringed by statues, leads into the Banquet Hall. I did not, until now, realize that Baroque, horror vacui, and jingoistic mythologizing could all be mushed together into one pseudo-glorious space. Rather than describe the things happening in murals across every inch of every ceiling and wall, and rather than try to photograph them, I cite the following label:

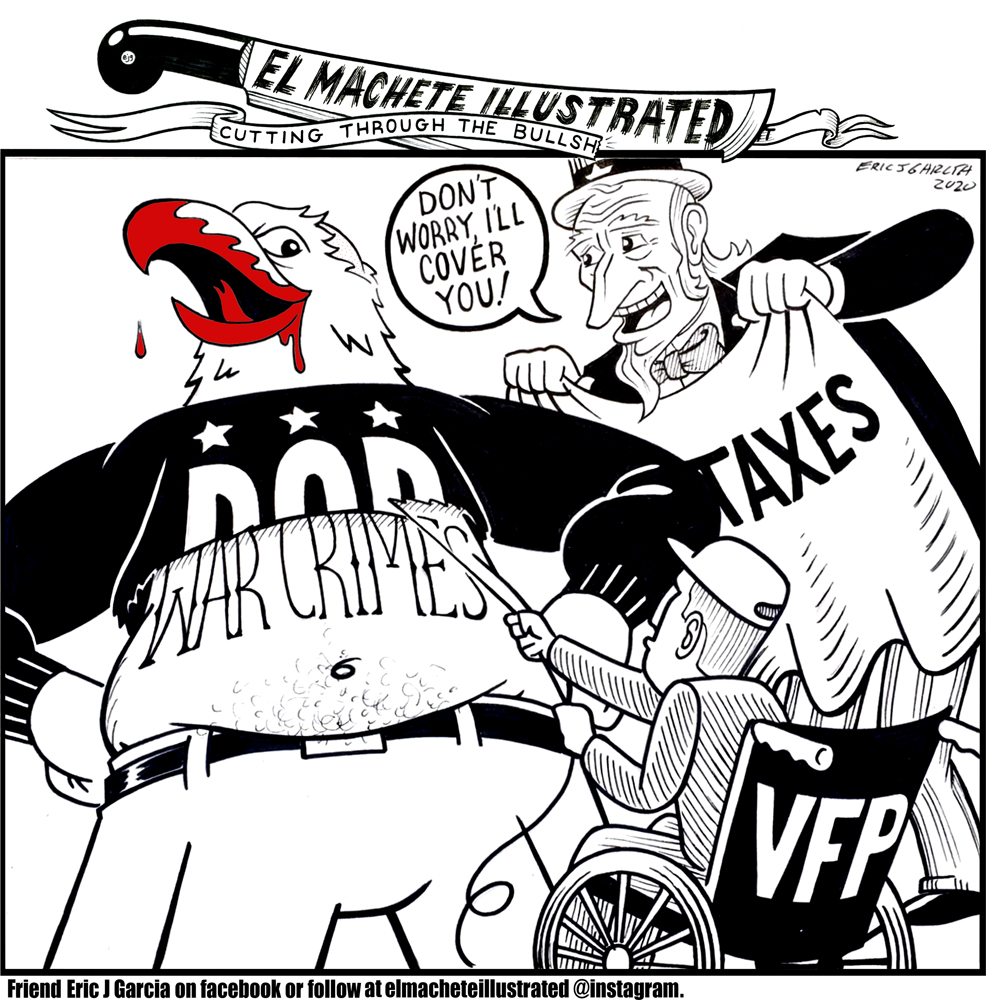

When I looked at that ceiling I looked at American men desperate for legitimacy and grandeur. And you get those qualities by pawning puttis off of Mother Europe and hurling together motifs from a wide range of European time periods and styles and calling it coherent. I thought about a sort of American occidentalism, an aspirational and frequently failing European-ness, the random grabbing of arbitrary motifs that seem to symbolize something. But this is also the look of a grandeur premised on exclusion, a grandeur anxious about its origins.

I wanted to retch and also scratch at it, which are signs that the art is working.

In the basement, there is a proclamation forbidding from membership everyone who was cool in 1919: anarchists, communists, and wobblies.

Fraternal orders intrigue me because they seem not only culturally other but also temporally distant. They are, of course, neither. Fraternal orders may be aging, and their membership may be dwindling, but clubs for white men, even if unformalized by ritual or shared animal-themed insignia, are still right here. That is why it is strange to witness the aesthetics of the Elks circa 1926, because however dated their shakey cornucopias in their birds’ nests of goldish molding look now, they remain, in spirit, ultra-contemporary.

There is a whispering room where meetings took place. It is curved so that the acoustics take a whisper from one side of the room and transport it to the other.

The Elks magazine, which I picked up a copy of on my way out, begins with a note from the G.E.R. (Grand Exalted Ruler), titled “If They Know You and They Like You, They’ll Want to Be Part of You.”

The magazine is mostly reports from lodges, which follow the same writing pattern: “In other news…” the brief begins. Then, “In more news…” And finally, “In further News…” For example: Riverhead, N.Y.: “In other news, lodge honored the ten winners of a patriotic essay contest for children in first through fifth grade.” Canoga Park, C.A.: “Lodge donated nearly 130 undergarments to the Sepulveda VA Medical Center.” Nashua, NH: “The lodge donated three basketballs and three soccer balls, on which there were drug awareness messages, and awarded them as door prizes.”

The Elks do lots of charity work with veterans and high school students, for whom they have a big scholarship contest. And the good will in the lodge briefs is so palpable, the hyper-regional so real. But I cannot help but wonder what three basketballs and three soccer balls with drug awareness messages might do that holding Purdue Pharma legally accountable for the opiate epidemic cannot. Nor can I help but wonder what the donation of “eight cases of soft drinks, nearly 180 pounds of pulled pork, and some coleslaw, bottled water, and dessert” to Sepulveda VA Medical Center can do that structural reform in veteran services and social services could not.

There is sporadic other content. There is an article entitled “Mole or Melanoma?,” which sounds like the title of a Chris Kraus novel. It is probably an interesting article but I could not bring myself to read it because I instantly began to worry about the status of my own moles.

Here is a drawing I made of my dad on the Chicago Architecture Foundation Boat Tour. I actually drew this in another time and place, but images often lie.

On the tour I saw a building set into the curve of a river like a ball might sit inside the ear. This image is appalling, because it’s a building, so the possibility of entering it is omnipresent.

That building curved like a jade pellet. And when the boat passed it I felt that I hadn’t seen the building from the inside of the river, I had only ever seen it pictured in a postcard. It was a site whose distance from me had been underscored. And I could only imagine it as a tourist imagines it, because when else would I see it from this vista, from the middle of the river, except as a tourist on a boat?

Here is my shirt, as modelled by whatever produce I could find in the kitchen.

Although I meant to write about something else, something public and therefore important, the next thing I would like to comment on is my shirt.

On the shirt, everyone is svelte and it is leisure time forever.

The graceful windows are open forever, the breeze forever catches the gauzy curtains.

It is a polyester knit, a button-down long-sleeve shirt, which, in the classic manner of seventies button-downs, treats the torso as a picture window into a dreamscape.

When I wear this shirt I think of my torso as a house in which I live. This is true: I look at my forearm and see the lady gazing out the window of my elbow. It is teatime or poker time. Actually, there are small glasses on the tables with their exaggerated marble tops: it is definitely sherry time.

I live in my shirt and so does my hurricane of images.