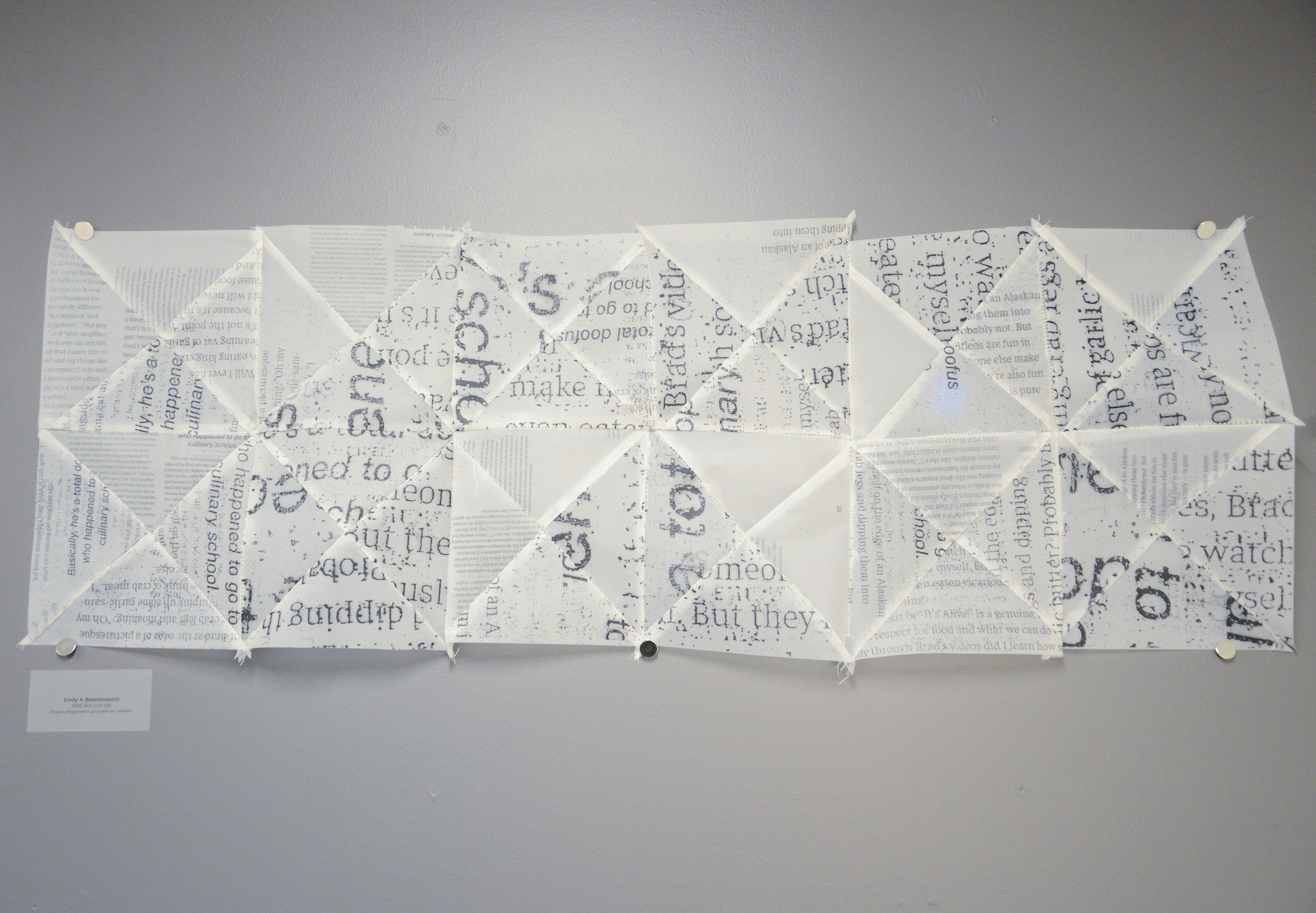

People have been known to reuse newspapers in a variety of ways — as flyswatters, gift wrap, and pet relief areas, to name a few. But as far as we know, Emily Beanblossom (MFA 2020, Sound) is the first to cut it up, blow it up via Xerox, and stitch the fragments into a quilted vellum collage. Sourcing text from our Entertainment Editor Georgia Hampton’s (MA 2020, New Arts Journalism) “The Joy of Cooking (and Eating),” Emily’s “FNEWS Cut Up” is the repurposed journalism we never knew we needed. We recently sat down with Emily to learn about her process and goals for the project.

What gave you the idea for this project?

This last year, I was really focusing on trying to gain more technical skill in the sound world — editing, mixing, learning the physics of sound and how it moves. I spent a lot of time on my computer, on a school computer in the studios, or reading articles for assignments. When I moved into my new studio as a second year grad, I had way more room to move around and work. I’d fallen out of touch with my old ways of creating, and I just wanted to sew, to make work that took up physical space. Also, I volunteered for my school’s yearly literary publication as an undergrad, and I missed working with text. This was also around the time I started to experiment with collage and notions of “the cut up.”

So, one Sunday I was roaming the empty hallways of MacLean, saw a copy of F Newsmagazine, and felt this impulsive urge to make a quilted vellum wall hanging with it as the muse. There was this immediacy to it — I didn’t have to think about what or why I was making. I love when that feeling strikes. Making this felt therapeutic because it got me working with materials that had seemed to fall out of my practice, materials that were so important to me at one point in my life.

In terms of process, materials, or objectives, does this project resemble others you’ve done in the past?

Before coming back to school, I owned a handmade soap company. I hand-wrapped each bar in a strip of fabric and a printed label. Sometimes, I asked friends to submit poems and I printed them on the inside of the label. For me, I think I do my best work when I’m thinking about combinations — what happens if I put this with that? Even if the combination doesn’t make immediate sense. What can I make with what I have? I’ve made printed broadsides that are also like “wall books,” artist’s books for children bound in knitted fabric, soap with song downloads, and lately, 5.1 surround sound pieces that combine natural environments with abstract music. I like thinking about medium overlaps and combinations. It keeps things from getting stale.

Take us through the process you used to assemble this piece.

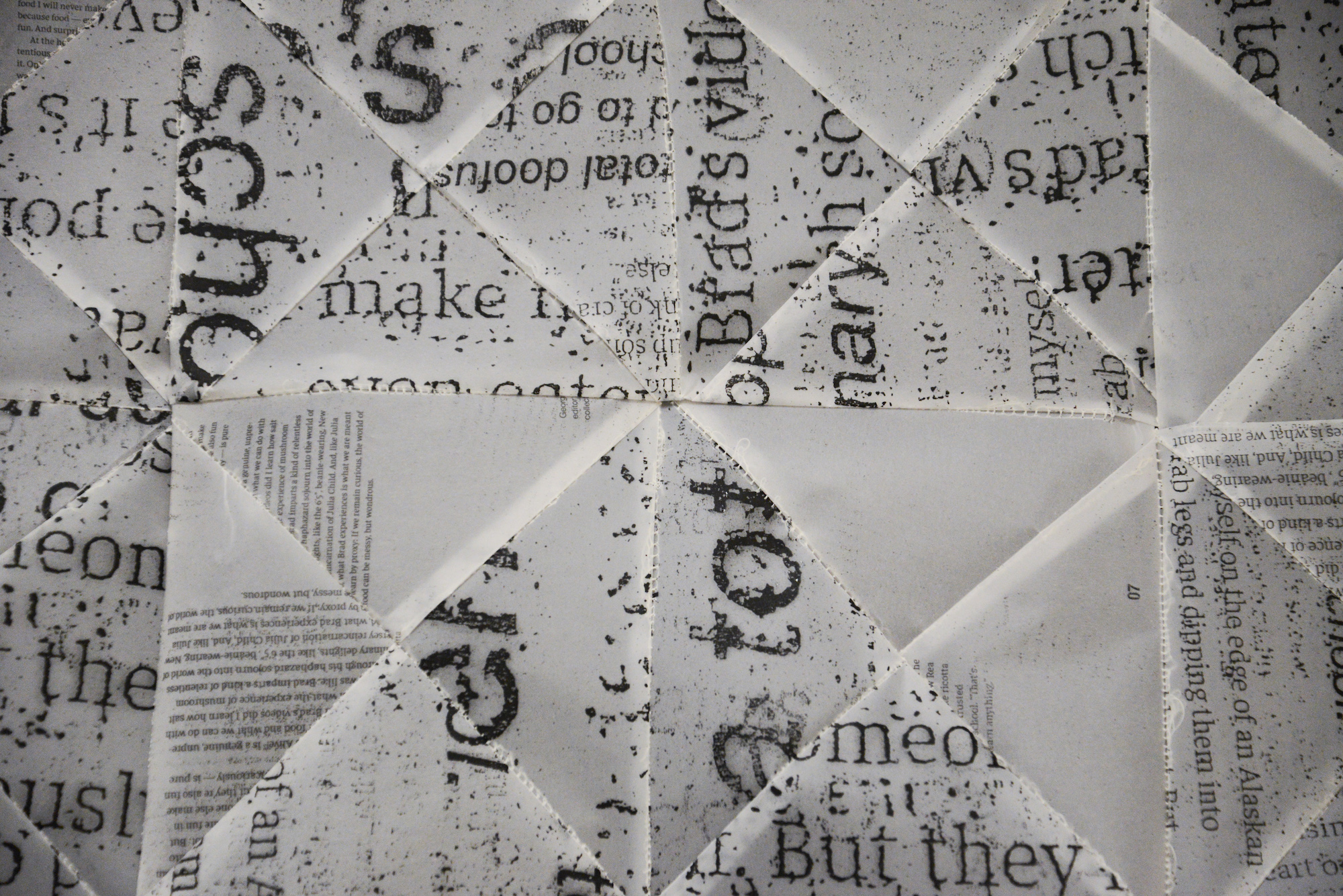

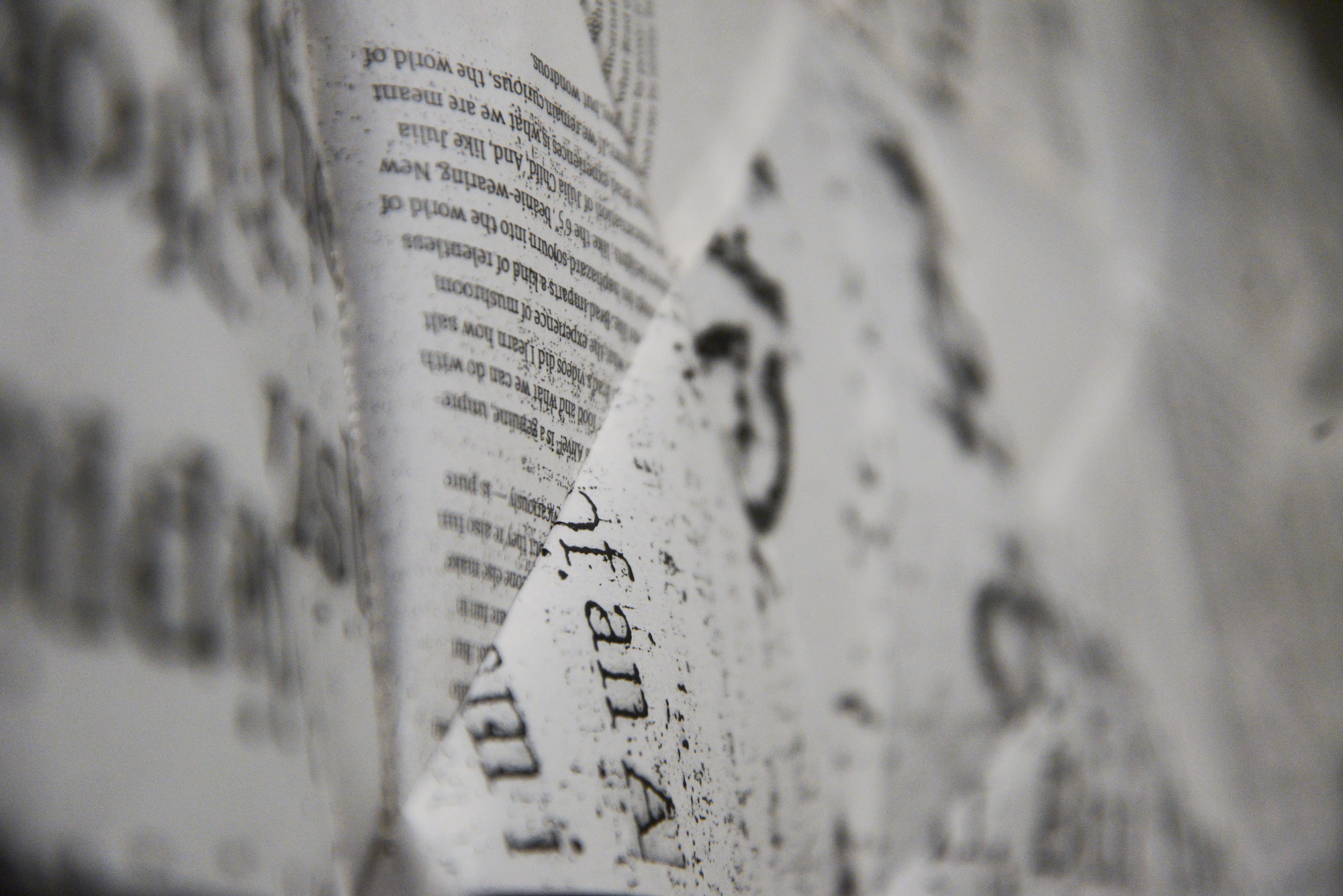

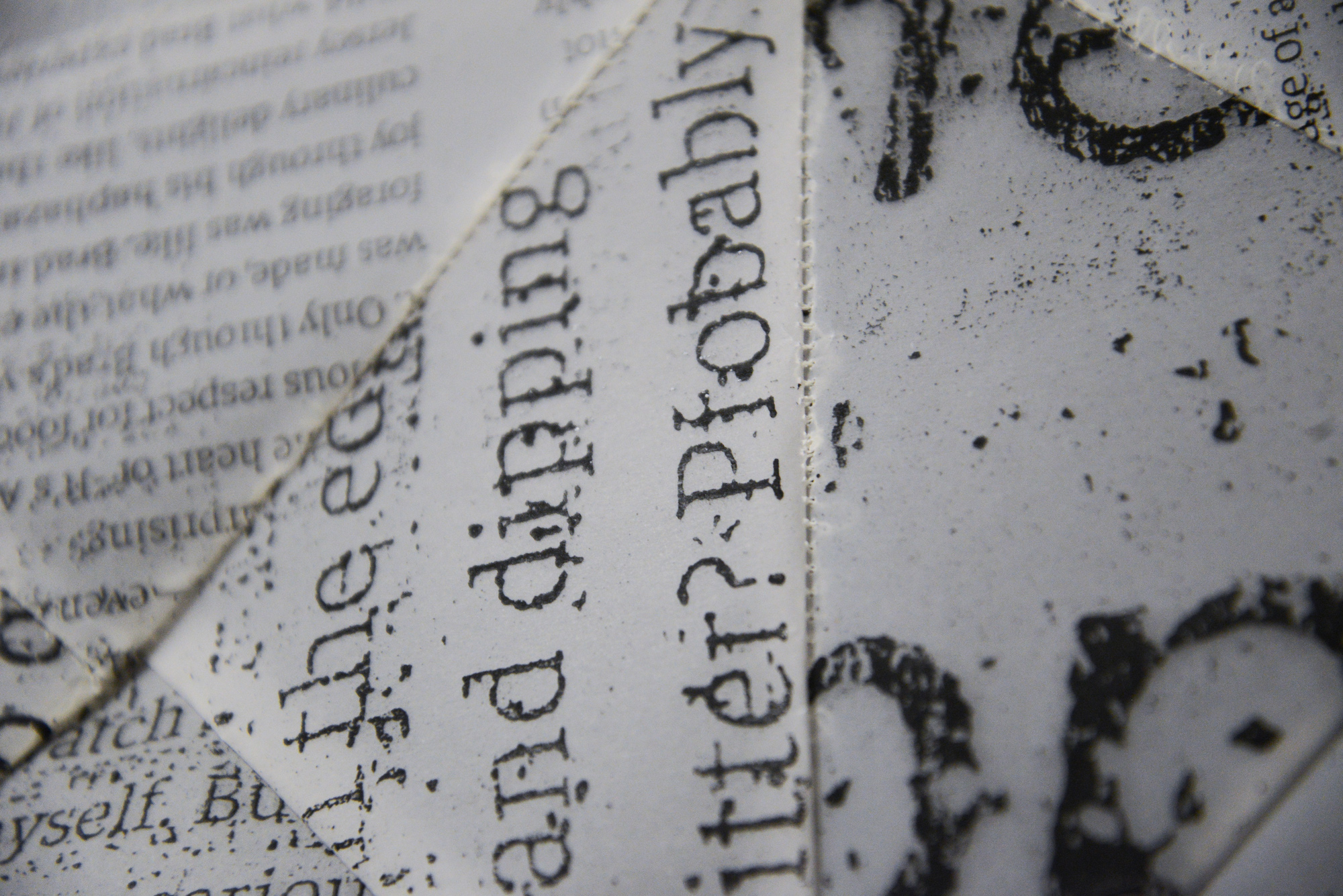

I brought out my old sewing machine, which was my mom’s, and on which she taught me to sew when I was little. In trying to do something that didn’t involve a laptop, I just found a copy of F Newsmagazine and Xeroxed onto vellum any sentences or words that jumped out at me, impulsively and quickly, without thinking. I blew some up and recopied until some words were distorted. Specifically, the quote “Basically, he was a total doofus who happened to go to culinary school,” from Georgia’s article about a TV chef really stood out. I loved it. Iterations of that, broken up, show up a few times in the piece. So, I went back to my studio, sliced the vellum up into triangles and started quilting them back together. If I had had more time, I would have made an even bigger wall piece, and I would want to incorporate some printmaking practices if it weren’t a piece about newspaper. But, since the medium is mass print, I felt the Xerox was appropriate.

Do you hope your audience reacts a certain way? If so, how? If not, how do you react to the pieces once they’re done?

I suppose I hope the audience finds it aesthetically pleasing and enjoys the tactility of it, the obvious disheveledness and unevenness — and really just look at it as a piece made for the sake of processing material we find in our world. It would be awesome if someone cut it up and re-assembled it with their own processes and materials. Maybe we can pull a name out of a hat, or hope someone defaces it. Once a piece is done, it’s not mine anymore!