A tried and true way to annoy anyone from Latin America is to refer to the United States as “America.” That name, many will respond, can refer to the entire Western Hemisphere, including, but most definitely not limited to, the United States of America. While in the U.S., one may, of course, refer to the whole continent as “The Americas,” but that term ends up reinforcing an “us vs. them” way of thinking, a refusal to understand the region as a system.

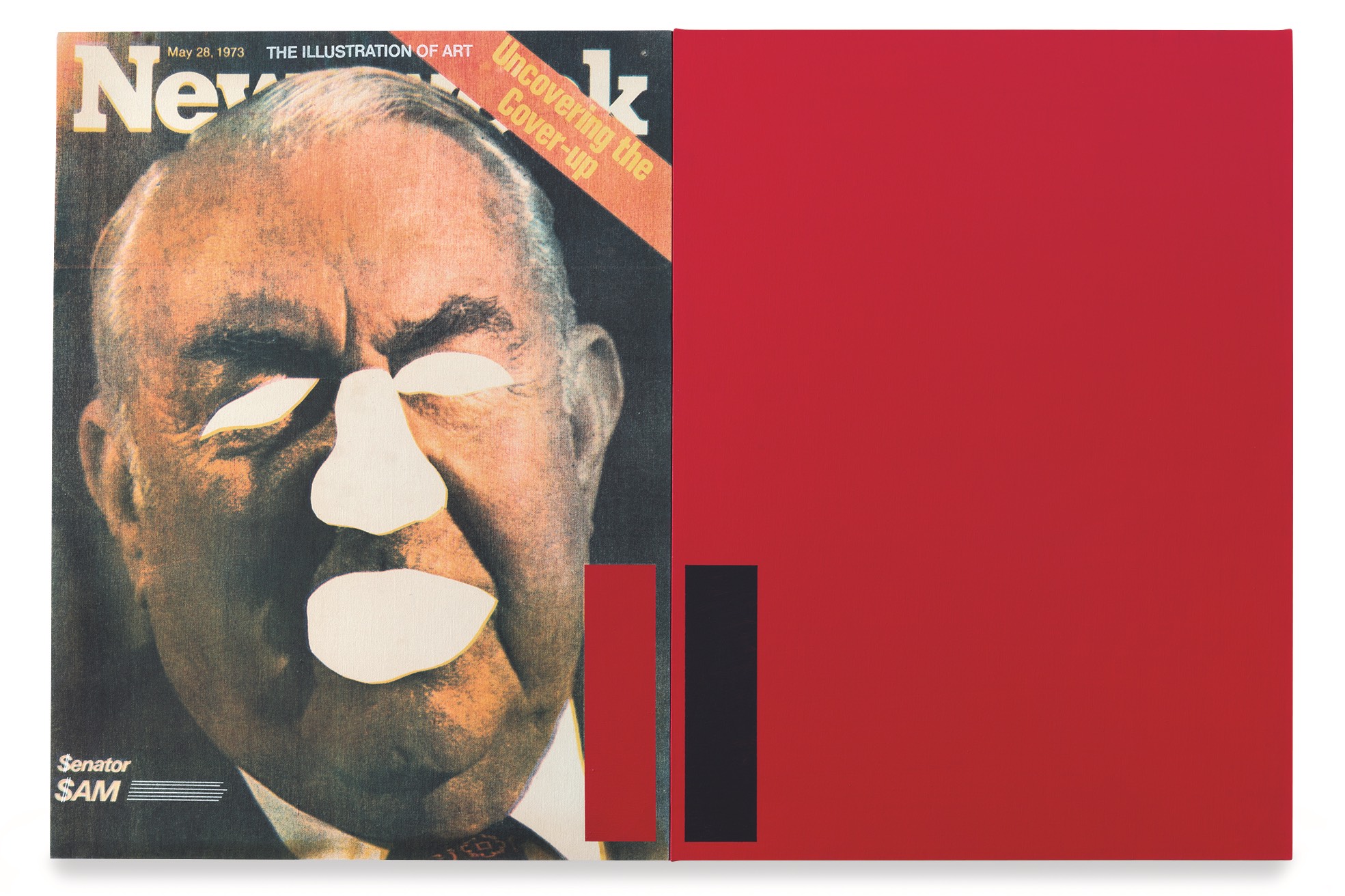

That little accent above the “e” in “Pop América,” the title of the Block Museum of Art’s exhibition on view through December 8, does so much more than translate the title into Spanish and Portuguese. It makes a point to look south — all the way down to Tierra del Fuego — and therefore understand the region as a whole. Of course, every Latin American country has its own specific issues in its history from 1965 to 1975, which is the exhibition’s time span. However, it isn’t difficult to draw parallels between them as they faced oppressive regimes and criticized a burgeoning consumerist culture inherited from the North.

The show’s thesis statement manifests in its titular piece, “Pop América” (1968), by Chilean artist Hugo Rivera-Scott. The cardboard collage, with its comic book-like spikes of fire and bubbles of smoke, follows in the footsteps of Roy Lichtenstein’s print “Explosion” (1967), on display next to it. The work, according to Rivera-Scott, implies the use of “pop” not only as shorthand for “popular,” but also as a verb: to burst.

No piece explores this more literally than Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles’ “Insertions Into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project” (1970). The series of soda (or “pop”) bottles, with white text printed on them after purchase, are meant to be put back into circulation to spread the messages to other customers. The text is hard to see when the bottles are empty, but becomes evident once they’re recycled and refilled in the factory. The interventions include the demand “Yankees go home,” encouragement to other consumers to add their own critical opinions, and instructions on how to use the object to build a Molotov cocktail.

Meireles’s piece exemplifies Latin American pop art’s concern not only with the political situations in the region, but also to U.S. imperialism, perceived most overtly in its consumer culture. The exhibition succeeds in showcasing this by including U.S. works in several key places. Just behind the Coca-Cola bottles is a print of Andy Warhol’s iconic “Campbell’s Soup,” and next to it hangs Antonio Caro’s “Colombia Coca-Cola” (1976), a rendition of the painter’s home country’s name in the brand’s universally recognizable cursive. They both reference mass-produced goods, but the latter takes it up a notch. It makes it political.

The common thread of explosions appears in ways beyond consumerist critique. “Erased Museum of Art” (1970) by Peruvian artist Emilio Hernández Saavedra is exactly what it sounds like: a photograph of an avenue in Lima, where that city’s main art museum is cut out and, as a consequence, obliterated. In “Lolita Lebrón, Puerto Rican Freedom Fighter” (1971), artist Marcos Dimas portrays his fellow countrywoman, who famously led an armed attack against the U.S. House of Representatives to demand Puerto Rico’s independence. Dimas’ screenprint presents the activist in a two-by-two grid with alternating reds and blues, playing on the commodification and idolization of celebrities, much like Warhol’s serializing of Marilyn Monroe’s face.

The show certainly ran the risk of trying to bite off more than it could chew — synthesizing the histories of multiple countries and appropriately representing them is a tall order. But “Pop América,” in its deliberate juxtaposition of artworks from different national origins, and inspired by different political situations, manages to summarize without simplifying, allowing the viewer to draw their own parallels. Furthermore, the show doesn’t drown the viewer in context, instead prioritizing each piece’s emotional impact.

In this sense, no exhibition about Latin American art in the ‘60s and ‘70s could be complete without referencing the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. The show dedicates substantial space — it compiles posters, stamps, and garments — to American artist Lance Wyman’s classic geometric ripples that defined the event’s identity. Just days before the inauguration of the international athletic competition, ironically decreed the “Games of Peace” that year, the Mexican government slaughtered hundreds of unarmed civilians who protested the organization of the games. The show places the official Olympic paraphernalia next to prints made by protesters who condemned governmental oppression. Wyman’s “Mexico 68” logo appears in an anonymous print next to a political cartoon-like drawing of a monstrous, sharp-toothed police officer swinging his baton at a kneeling protester.

The work in “Pop América” is now half a century old — yet it maintains its relevance. Puerto Rico continues to fight for political power and accountability, especially after a poorly managed and underfunded post-hurricane recovery. Brazil still grapples with a culture of strong business interests as the Jair Bolsonaro administration rolls back human rights for minorities and responds with negligence to the Amazon rainforest fires. Mexico deals with state violence to this day — 2019 marks the fifth anniversary of the 43 disappeared students in the southern teaching school of Ayotzinapa. The pop was certainly heard around the world, but it’s still echoing off the walls.