In last Monday night’s episode of “The X-Files” — the third installment of the show’s revival after more than a decade off the air — Fox Mulder turns his habit of frustrated pencil tossing from the ceiling of his basement office to a poster on his bulletin board. Pencils gouge the now-iconic image of an unidentified flying object (UFO, if you will) flying above a remote patch of woods, with the text “I Want to Believe” emblazoned in white letters at the bottom of the photograph.

As Dana Scully enters the room, she laments his hostility towards the resilient picture. “What are you doing to my poster?” she asks. Originally purchased by Mulder at a D.C. head shop, the poster has been enshrined in his hermit headquarters since 1993. It became Scully’s over the years of her work on the X-Files — an admission of her growth over the course of the series. She began as a serious, scientific, and skeptical medical doctor ; now she is willing — if not entirely wanting — to believe. The poster is one of the show’s most integral symbols, one that has been destroyed and salvaged again and again.

The original image has a complicated history, complete with copyright infringements over “genuine” UFO photos taken in Europe that prompted a photo swap. Most intriguing, perhaps, is show runner Chris Carter’s inspiration for the piece: pop artist Ed Ruscha.

Long before everyone and their Pinterest-loving cousin started sharing “inspirational quotes” on top of whimsical photos, Ed Ruscha was juxtaposing image and text in new ways. This was a time when it was rare to see words inside of — instead of alongside — works of fine art. The only remaining prop poster that wasn’t stolen or destroyed was given by Gillian Anderson to the Smithsonian in 2008. Carter told the museum about the poster’s inception:

“The original graphic came from me saying, “Let’s get a picture of a spaceship and put — Ed Ruscha-like — ‘I want to believe.’” I love Ed Ruscha. I love the way he puts text in his paintings.”

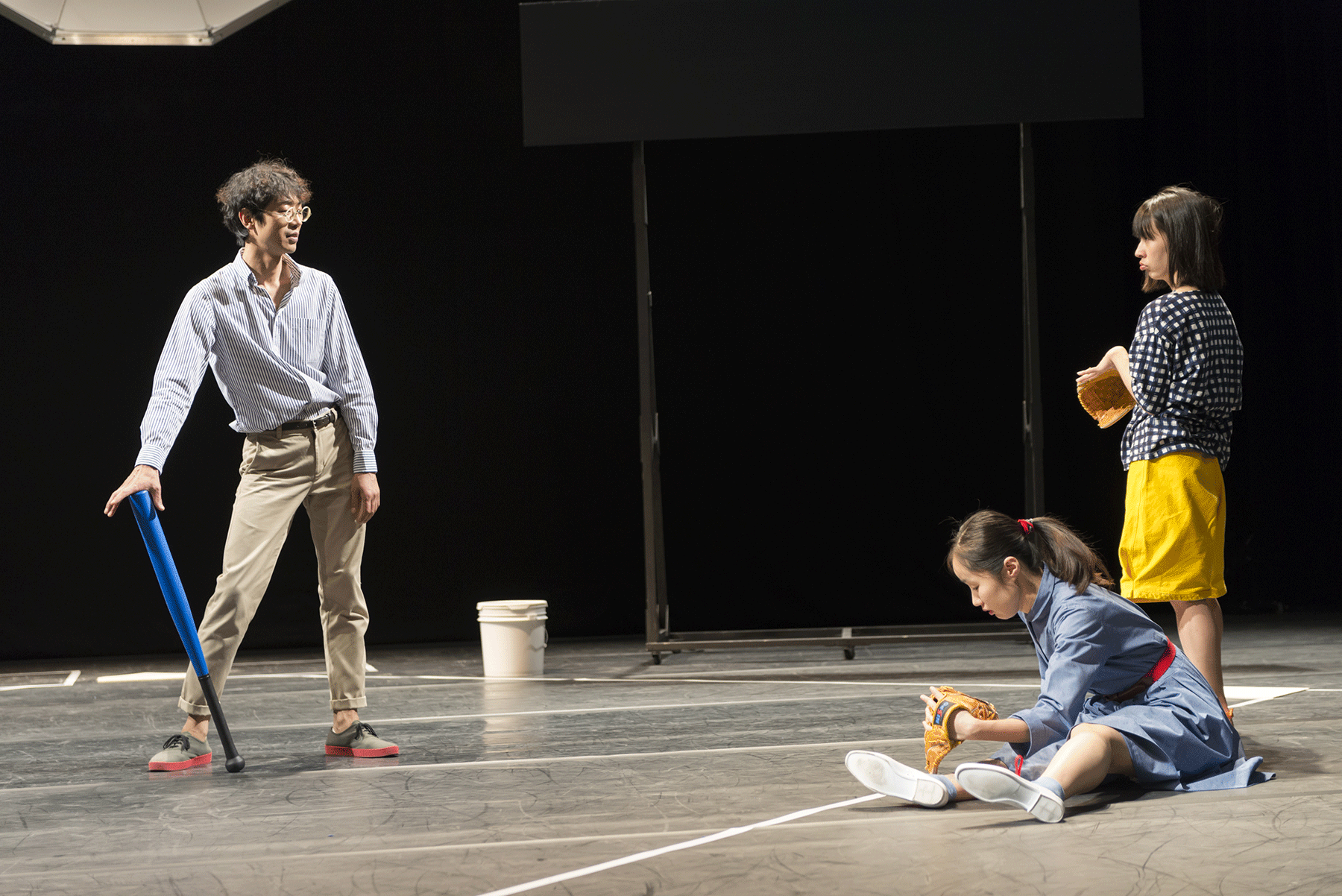

A Nebraskan born in 1937, Ruscha was a contemporary of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. He had a background in graphic design, which is apparent in his works: Ruscha’s pieces often look less like the paintings they are and more like advertisements or magazine headlines. A piece titled “Baby Jet” from 1998 and contemporary with “The X-Files” shows how similar his work is to Carter’s poster:

Beyond the “I Want to Believe” poster, it seems Ruscha’s art may have influenced Carter’s entire show. Consider the piece “IF” from 1995, which came out only two years after “The X-Files” began to air.

Ruscha’s oeuvre is repetitive, and if he painted pieces like this earlier and Carter was familiar with his work, it wouldn’t be surprising if the pop artist’s eerie images helped Carter cultivate the spooky aesthetic “The X-Files” pioneered.

Conspiracy? If Mulder has taught us anything, the answer is always, “yes.”

As “The X-Files” begins a new chapter in its decades-long life, the “I Want to Believe” poster is a welcome sight. It is a testament to the power of symbolism, a constant across the series’ 200-something episodes and two movies, a proto-meme surging back into mainstream pop culture from its otherworldly origins in pop art.