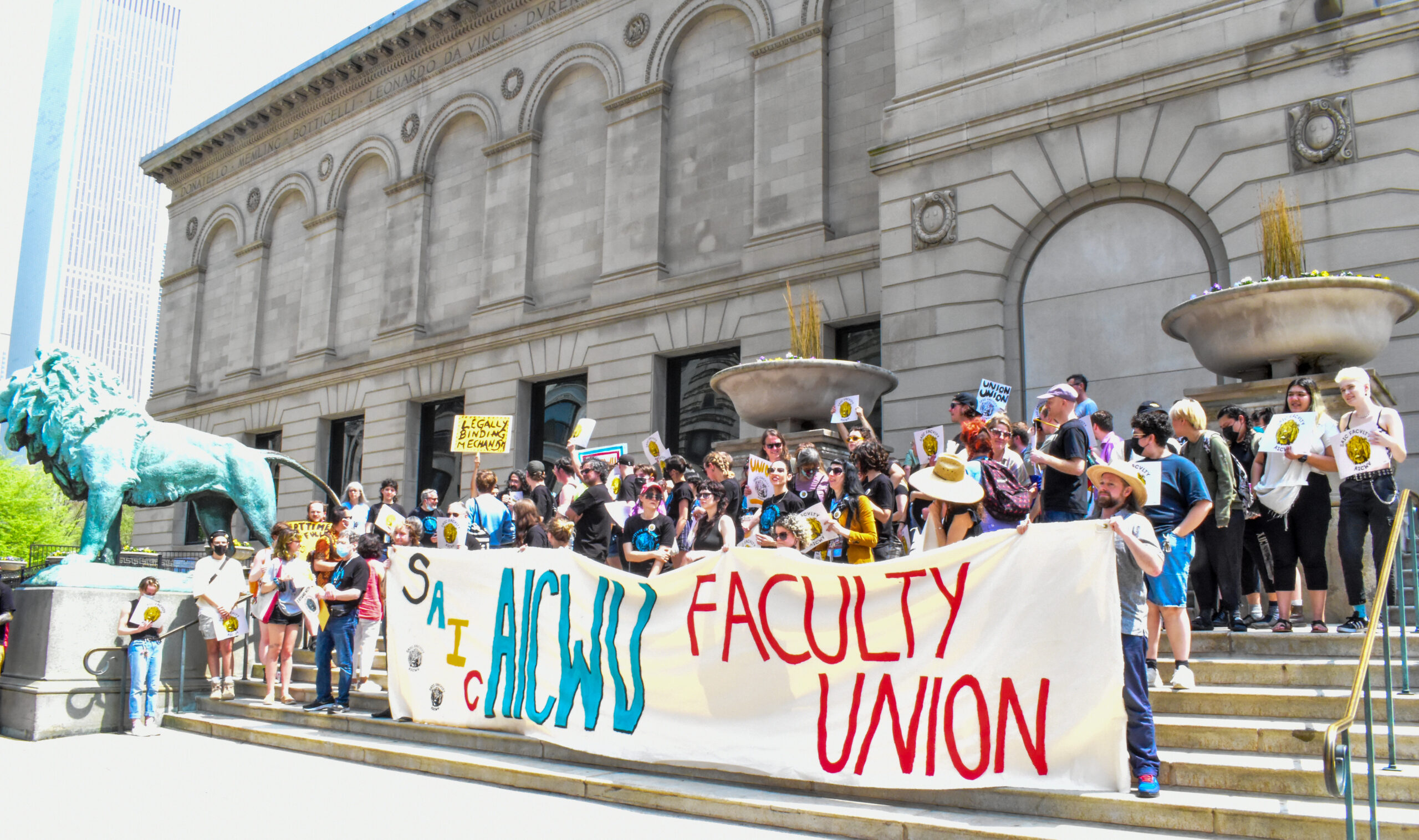

Does a Pairing With Science Really Work?

Illustration by Megan Pryce

Interdisciplinarity, a term frequently tossed around among students and faculty alike, alludes to an open, fluid, practical and theoretical understanding of the world supported by investigation and configuration. Definitions of what that really means and methods for implementing interdisciplinarity within a curriculum are still forming.

Initiatives to build bridges, for example, between art and science are a trend in academia and beyond, and have been for some time. School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) president Walter E. Massey, a distinguished physicist, has encouraged this approach to education. The school hosts Conversations on Art and Science, a series of lectures by artists and scientists from around the world, launched in 2011 by experimental physicist and SAIC instructor Kathryn Schaffer.

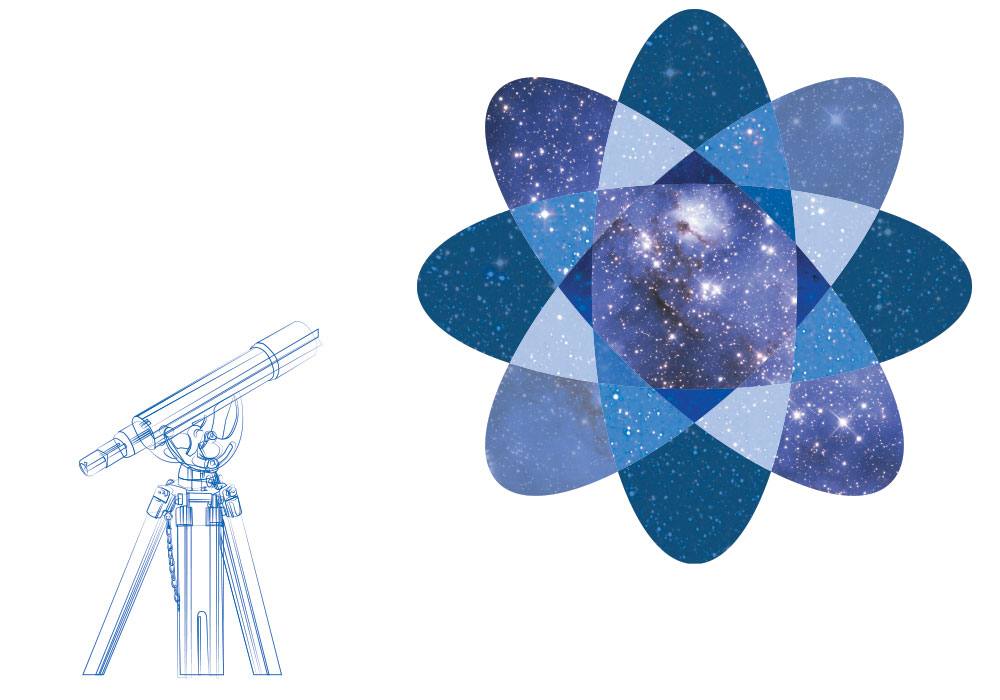

Schaffer’s contributions to astronomy make her a unique member of SAIC’s faculty. Her work on the South Pole Telescope (SPT), a 30-foot telescope in Antarctica, studies the growth and structure of the universe.

Collecting and interpreting numbers is a “very messy, complicated process of turning raw data into something that answers a question,” said Schaffer in her recent tenure presentation, “Raw Bytes to Real Knowledge.” She also works with a group of scientists at the University of Chicago on the SPT project and brings aspects of other astronomy projects to her work at SAIC, furthering dialogue and collaboration between artists and scientists.

This spring, Schaffer and Paola Cabal, a member of the painting and drawing department, will co-teach a six-credit studio and science course, Articulating Time and Space, “to creatively envision concepts derived from rigorous scientific inquiries into the universe, the principles of physics, and dimensional spaces,” according to the class description. The core of this opportunity is interdisciplinarity.

Similar in nature is SAIC’s Data Viz Collaborative course, based on collaboration between SAIC and Northwestern University faculty and students. Jessica Barrett Sattell, a graduate student and journalist (and an editor at F Newsmagazine), is a member of one of the teams that work alongside each other to think about information visualization from data and create artwork from their findings. “We’re all fascinated with data and how it can be applied to understanding and explaining many different things,” Sattell said. Students’ different roles and skill sets create a collaborative environment in the course because everyone has “to work together to support each other.” She sees more similarities than differences between students with art backgrounds and those with science backgrounds. Collaboration allows different methods of investigation to influence how we understand the results of research, creating the potential for an entirely new outlook on the knowledge gained through research, experimentation, and the creative process. “[Artists and scientists] share a pretty similar line of inquiry into problem-solving that involves a process of testing and feedback and proposing multiple possibilities to come to a solution,” said Sattell.

Problem solving is inextricable from the creative process of making artwork. The making process itself influences the concept, and the concept determines the methods and materials suitable for communicating an idea behind the work. Creating work as an artist is a process of experimentation, an essential component of scientific inquiry. Scientist Buckminster Fuller believed that intuition as well as experientially gained information, according to author Dana Miller, were integral parts of his “design science revolution,” which needed artists as much as scientists and designers. Bringing science into the art studio, Fuller glorified the potential artists had to legitimize scientific discoveries.

Schaffer is skeptical about whether artists can make substantial contributions to science directly, but she says that is beside the point, because working with representation and algorithms “can relate to individual art practices.” Research processes and methods of visualization overlap in science and art, and we can explore how we understand those commonalities through collaborative conversations, while discussing “what is meaningful about highlighting those commonalities.”

Philosophical questions regarding why a scientific investigation begins in the first place are not necessarily relevant, Schaffer says. “The nature of the conversation about the significance of results is going to be different depending on which people you are bringing together.” The same can be said about the conceptual meaning behind of a piece of art. Just as there is intrinsic value in a work of art that exists purely for the sake of art, “there is value in knowledge for its own sake.”

Establishing interdisciplinarity between science and art within an institution makes sense as a way to encourage this type of learning, but finding the right structure for it can be difficult.

Visual and cultural studies as a discipline is still trying to substantiate itself as interdisciplinary, writes James Elkins, a Professor in Art History, Theory and Criticism at SAIC, in his book Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction. Although attracted to “the possibility that several disciplines might work together,” Elkins is “not interested in confirming such a configuration as a new discipline or arguing that it is interdisciplinary” and is unsure “what relation obtains between the kind of work that seems most amazing, deeply insightful, provocative, and useful, and the disciplines to which it owes allegiance.”

Nothing is isolated, even our universe as a single system is being called into question. Infinite connections exist between everything if you know how to look for them. The patterns we observe in the world around us are made meaningful through their interpretation and representation, in both art and science. As individuals in collaborative groups we can create constellations of meaning and create new conversations, new questions, and new methods of investigation — and come together as curious and creative artists and scientists.

Exploring the links and correlations between superficially separate areas of society and how they work together create a better understanding of ourselves a collective. Understanding the structure of the universe may not have “practical applications in a direct way any time soon,” Schaffer remarks, but it’s still “important for people’s world view to really reflect on the context in which we live in nature.”