Beijing Silvermine in Museum of Contemporary Photography’s Archive State Exhibition

A woman in a mint green dress leans against a shark enwrapped by a sea monster’s tentacles. A young man perches on a crescent moon while a dusky city glows behind him. Neon splotches and acid marks that hover around the images’ edges signal not only time’s wear on the physical objects, but also the breakdown of everyday life at the time of the pictures’ capture. Since 2009, French photography collector and editor Thomas Sauvin has purchased negatives of images from a Beijing recycling center, where they were being melted down for the silver nitrate within them.

Sauvin’s Beijing Silvermine presents moments from China’s capital in the period of change following the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976. The archivist had been living in China for nearly ten years when an online search for old negatives led him to the recycling center’s wealth of images. The collected photographs now appear as part of the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s Archive State, which showcases the work of several artists who make use of found material, raising questions around how we define authorship.

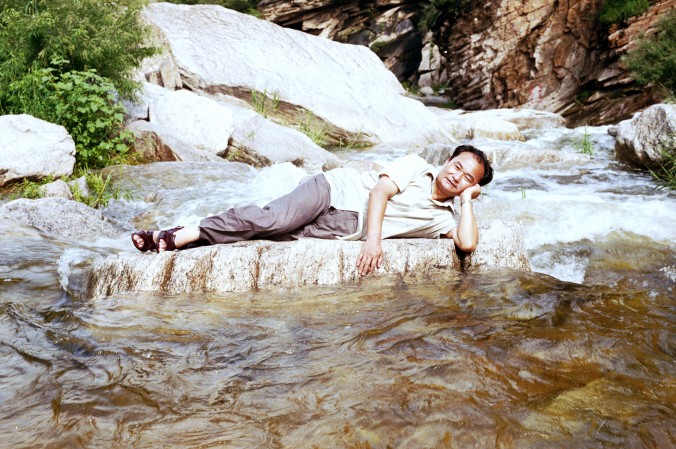

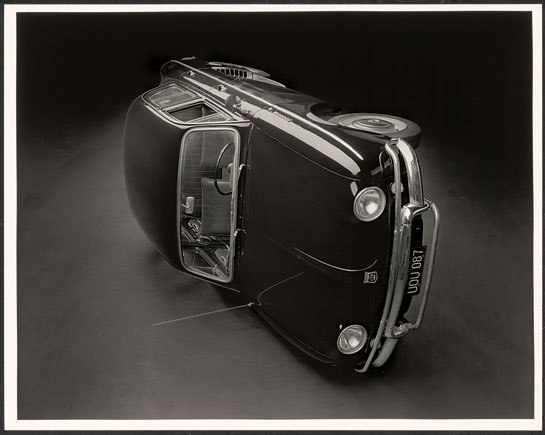

The photographs in Beijing Silvermine are often playfully absurd, frequently creating a dreamlike effect. Their subjects interact with both outlandish props and commonplace objects, engaging the physical world in unexpected ways. Gif-like animations of photographs, created in collaboration with artist Cari Vander Yacht, emphasize the comedic aspect of several pieces. The pictures are openly posed, and the people in them make no attempt to hide their awareness of the camera: the photos’ subjects appear as if they wish to be presented, within moments that they have chosen to record. Maybe it’s this honest quality of the photos that limits any feeling of voyeurism in the exhibit. Sauvin has said of his work, “Basically, I don’t see myself as an artist, but I see myself as a photographic collector. So, what I do is I find images that would have been lost and I show them. In a sense, I don’t change or modify the pictures. I just show them as they are and then what is important for me is the stories that emerge organically from the archive and what they say about people.” The photographs are presented with respect to the personal moments they contain, and focus on historical content.

One section of the exhibit consists of smiling women standing beside televisions, refrigerators, and other domestic appliances. Beside this area, there are several photos of people posing with food from McDonald’s. The turn toward consumerism caused by China’s economic opening to the world is a major theme in the show. One photo displaying a young boy’s nonplussed expression as he stands next to a grinning Ronald McDonald captures the moment of colliding cultures. The fact that so many of these photographs were discarded signifies that the events recorded have lost importance; however, their vast number reveals their former significance.

Other photographs in Beijing Silvermine reveal a society in which values are shifting. The trips to Tiananmen Square captured in many photos are signs of greater economic prosperity. Documents of trips abroad to Paris’s Louvre feature camera flashes reflecting off of masterpieces. The moments captured in these photo- graphs are those of leisure and the status that comes with it. Their repetitiveness reveals the shared ideal of success being strived for, despite the frequent sense of looseness and play. The amateur photography in this exhibit highlights the medium as a collective method for cataloguing one’s successes during a pivotal cultural moment. This instinct is not unique to China, and almost seems natural in today’s landscape of social media.

A sculptural piece made in collaboration with Chinese artist Lei Lei, Recycled, references how Sauvin encountered the filmstrips. In the work, a pile of singed plastic photographs is interspersed with screens that flash similar images in quick succession. The piece echoes the modern move toward digital photography, and the impermanence of the moments recorded in that format. Because of the sheer amount of images produced, they end up lost. Though analog pictures may end up on the junk pile, they still take up physical space, a presence emphasized by the sculptural shift in materials from film to volumetric form. The ultimate disposability of digital photographs and difficulty in archiving them is illustrated by the rapidity with which they flash across the screens; they disappear before the viewer has the chance to contemplate their content.

Outside forces have caused some of the faces in the photos of Beijing Silvermine to fade. The discarded photographs in this archive contain moments of both pleasure and anxiety. With this collection, Thomas Sauvin exhibits awareness that many images of the past will be lost, regardless of attempts to preserve them through archiving. The remembered joy taken in ephemeral moments, however, may remain long after the photo is snapped. With Beijing Silvermine, Sauvin suggests that those histories, rich with both joy and abandonment, are worth salvaging.

Archive State is showing at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from Jan 21-Apr 6, 2014.