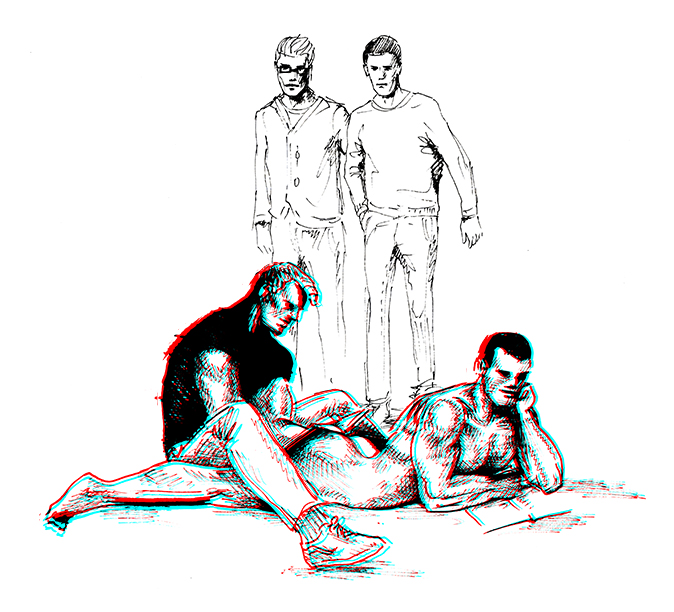

Homonormativity and Televised Representations of Gayness

Illustration by Berke Yazicioglu

When identifying with a social group, you also attend to a practiced framework of culture tied to it. This often happens as you choose to participate in some of a group’s practices and share their values, while opting out of others. Queer culture (“queer” as an umbrella term here) is an interesting example, since it is one that first involves an identification process, followed by locating the queer self within a larger framework of people with similar traits. However, it is more complicated than this. Aside from seeing oneself within a group of people, queer culture has a heritage that is self-taught and must be individually reasserted. To be marked or mark oneself as queer is to indicate your relationship to a set of characteristics that people then hold you to. To say that you identify as gay automatically places you beneath a cultural rubric.

Equally complex is assessing media representations of gay identities, which often essentialize the fluidity and diversity of gay subjectivities. HBO’s new sitcom series, Looking, has further confirmed the arrival of an ostensibly new gay male mass-media stereotype in the twenty-first century. A wary and critical eye toward the mainstream media has grown alongside the development of gay culture, and yet media images still serve an important role in the learning of gay culture — for better or worse. What, then, is being learned from shows like Looking?

Looking presents three men plus some recurring friends and relationship partners, all of whom could be considered well-adjusted, stable, though not without the usual ups and downs of people in their early to late thirties. The first episode immediately shows a pleasant assortment of gay life, past and present. It begins with a romantically antiquated failed cruise session in the park and later depicts an equally disappointing OkCupid date. Sprinkled in between is a spontaneous threesome as well as a proposal from one of the characters to his boyfriend that the two move in together.

It’s more than fair to say that these are refreshing renderings of gay identities as opposed to previously shady or single-dimensional characters that once appeared on television. The problematic nature of those older representations was in part due to their incomplete development as characters as well as their placement into the media world as connotatively queer rather than directly queer. They were closeted, and their queerness was only tacitly addressed, at best. Even so, Looking addresses gayness in limited terms, failing to account for the wide array of gay identities that exist. It is a dichotomy between thinking about gayness as a matter of an identity instead of as a subjectivity.

Postulated most recently in his groundbreaking book How to Be Gay, David Halperin states that gayness, aside from natural sexual preferences, is a learned practice as well as an affinity for certain cultural forms. His analysis is through the lens of a gay subjectivity, rather than identity.

Subjectivity versus identity is a crucial sticking point for How to Be Gay. Early on in the book, Halperin attempts to cancel the “we are the all the same” slogan in favor of a more complex notion of subjective experience, calling out normative rhetoric as narrow and dated. In other words, “identity” fails to elucidate experience. In Halperin’s view, it only assigns a marker. It is not uncommon to hear: “Yes, I identify as ______, but it certainly doesn’t define me.” In thinking about gayness, Halperin says there’s more to it than that.

What we find in Looking is similar to other representations of gay men in recent films and television shows (excluding children’s television, for the most part). We often see men who are stable, healthy, and aptly masculine. In many of these cases, standard ideas of masculinity are especially prominent. These are men that typically pursue exclusive relationships, are well-versed in culture, and hold a stable (if not generous) 9-to-5 job. Perhaps they have a job in set design, something that is both creative and requires intensive amounts of manual labor. Or maybe there’s the quintessential “geek” who programs but knows how to have fun on the side, too. And, chances are they know their way around a bar: there’s the expected glass of white wine but also the requisite glass of whiskey (served sour if he’s the “fun” one in the group).

These men also go to the gym and have a perfect image of upper body strength: not too big, not too small. They also take time to be “420 friendly,” as they may say on their Scruff account profile. While career success is prized, a key element to many of these representations is the structure of their living situation. Looking eventually involves a couple moving in together. In the case of the single-season NBC show The New Normal, the plot centers around a committed couple of two men who are on a mission to have a child and eventually do so via surrogate. Despite the commonality here in actual same-sex unions and largely conventional birthing practices, the shows follow a heteronormative template. They illustrate cohabitation between committed partners and/or the bearing of children. These heteronormative situations seem hegemonic, as they are the narrative standards allowing gay men admission into the mediascape.

Those aspects, however “positive” in their own right, follow the “we are all the same” state of mind. What has happened, and it’s no surprise, is yet a new type of homogenization of gay identity, further charged with normalizing features of masculinity and heteronormativity. It’s almost as if the gay male character was hurled out of the closet and into the country club, an exaggeration of course. Yet, it’s plain to see that extreme change has occurred in conceptualizing gay identities, and thinking of it as a matter of multiple subjectivities is a step in the right direction. What we can hope for is a maturation of these media representations into more multidimensional gay characters that neither overemphasize nor underemphasize gayness. Achieving a balancing act, however, may be an eternal struggle and criticism of media representation.