The Gender Bazaar Takes The Expression of Identity to a New Level

“Au Bazar du Genre” (The Gender Bazaar) is one of two inaugural exhibitions taking place at the newly opened Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilizations (MuCem) in Marseille. The exhibition considers an evolution of masculinity and femininity in Mediterranean societies and also addresses another subject which has recently polarized France — homosexual rights.

During the Cannes Festival in May, no fewer than eight films in the competition dealt with same-sex relationships. The Palme D’Or was awarded to “La Vie D’Adèle” by Abdelatif Kechiche, an adaptation of the comic book “Blue is the Warmest Colour,” following the loving relationship between two young French women. At the same time in Paris, the Constitutional Council validated a law promulgating same-sex marriage. This apparent visibility of all themes homosexual cannot be mere coincidence. Is there a wider reflection in the arts of this pivotal political moment?

In the past, gay life in French cinema had been depicted almost exclusively via comedies and farcical scenarios. The most popular actors of the country have, one after the other, starred in a series of films with repeated scenes of ludicrous misunderstandings and cascading stereotypes: “Gazon Maudit” (1994), “Pédale Douce” (1996), “Le Derrière” (1998), “Le Placard” (2001) and “Do Not Disturb” (2012), to name just a few. Unlike the world of cinema, over the last 10 years it has been almost impossible to find an exhibition dedicated to the theme of homosexuality in French museums. The scarce exceptions have tended to focus exclusively on male relationships. Even more frequently, representations of homosexuality have been equated with transgender identities and drag culture. However, the MuCem exhibition addresses homosexuality within the context of a struggle for equal rights and for the freedom of both women and men to define their own gender, sexuality and role in the social space of France.

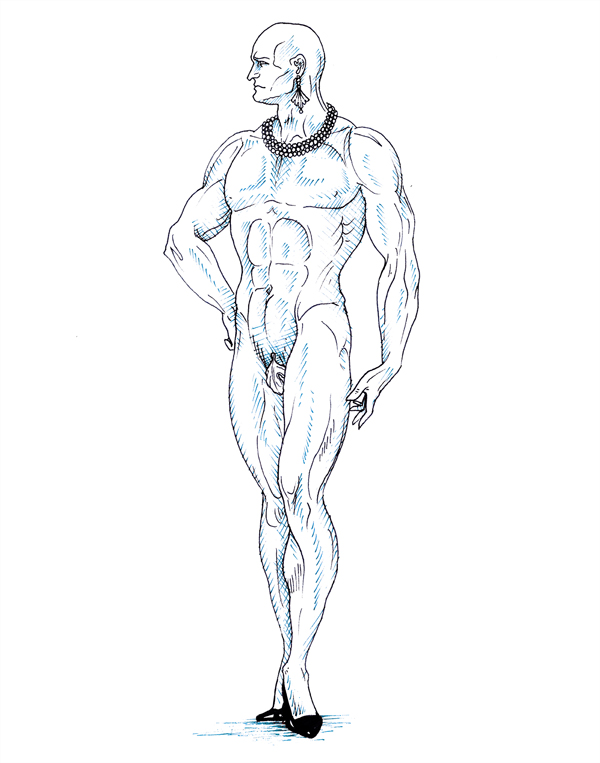

Divided in honeycomb-shaped sections, the exhibition space is organized around five main reflections on sexuality, gender and freedom of choice. The first one is dedicated to motherhood, displaying an eclectic mix of ancient Mediterranean fertility statues, posters from abortion rights campaigns and an overview of rituals and traditions related to female virginity in Mediterranean societies. Homosexual rights are dealt with in the second section of the exhibition, in another improbable collection of media ranging from humorous art by Pierre et Gilles, to video archives of gay pride in Marseille, Istanbul, Tel-Aviv and Beirut. The other three reflections — transgender, dating conventions and gender equality — are addressed in a similar bazaar of visual and auditory media.

This exhibition opened two weeks after the law authorizing same-sex marriage was adopted in France following six months of heated debates and protest marches. Passed by the National Assembly on April 23, the bill legalizing gay marriage in France is said to have divided the French populace. It took more than 24 weeks of debates, protests and counter-protests for France to finally become the 14th country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. Opponents to the bill marched in the streets, claiming that legalizing “marriage for all” would upset the foundations of the Civil Code and human identity itself. They also argued that it was a profound violation of a child’s “sacred right” to have both a mother and a father at birth.

The opposition to the bill was much more virulent than most had expected. How is it that France, the supposed home of human rights, had such a hard time legalizing and accepting gay marriage? Was this a genuine reflection of the concerns of an outraged citizenship, or was something more political at work?

Many believe the divide between pro- and anti-gay marriage was little more than an extreme example of the usual right-left polarization inherent in French politics. When virtually all members of the UMP (Union for a Popular Movement, a center-right party) started attacking the bill, it was not same-sex marriage that they were contesting but purely and simply the first major societal reform from the new center-left government.

Representatives of the center-right party who had previously shown no opposition to same-sex marriage — some of whom had, in fact, previously defended it — suddenly changed sides when the Socialist Party brought in the draft bill. The game was ratcheted up; UMP representatives invited followers of the party to protest, some even going as far as marching alongside elected members of the National Front, generally considered a fascist party beyond the realm of political respectability.

A bill that was supposed to improve homosexual people’s condition and public acceptance of homosexuality ended up provoking an unexpected surge of homophobic comments and violence. In Nice, Paris, Lille and Montpellier there was a perception that homophobic attacks were increasing. Certainly, there was much more media coverage of these incidents. In reaction to these events, many French people marched in the streets to show their support for the gay community and to condemn homophobia. A part of the French media made a mockery of the anti-gay marriage movement, broadcasting short video clips that gathered together the most ludicrous arguments formulated by demonstrators during interviews.

Now that the law has been validated by the Constitutional Council, and the two main parties have found other topics to disagree on, tensions have considerably diminished. That being said, they have not completely disappeared. A few mayors have failed to apply the law, refusing to officiate at same-sex weddings. If the debate has left the political arena for art galleries and cultural institutions, some of the violence has too. A photographic exhibition by Olivier Ciappa in the third arrondissement in Paris was vandalized twice in less than a month. His show, “Les Couples Imaginaires,” is a series of 34 black and white portraits presenting various French celebrities as imaginary gay couples.

Some spectators may have frowned, or let a stifled remark slip in front of a photograph at the MuCem’s inaugural exhibition, but there has been no violent reactions whatsoever up to this date. It is certainly due to the way homosexual identities are addressed in this Gender Bazaar — as defined by one of many decisions individuals might make regarding their sexual, social and physical identities. Sandwiched between old advertising posters defending the legalization of abortion and fashion photographs of women wearing hijabs, homosexuality at the MuCem is not shown as a revolutionary way to love, or a profound disruption of the social order, but as what it truly is: a way of being among a thousand others.