Book Details: Power On by Ginger Ko. The Operating System, 2021, $18

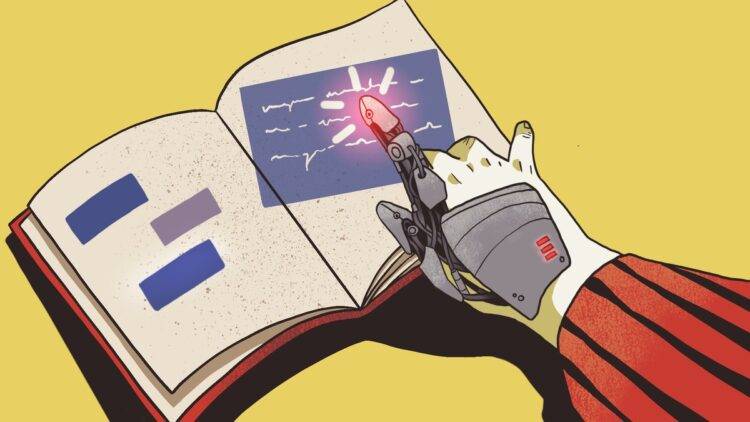

Ginger Ko reveals a glimpse into the truth behind creation. Popular belief situates the creator as distinctly divorced from the creation, but with her newest poetry collection, “Power On,” Ko unlades the reality of the relationship between the tool and the senses. Her book of poems reframes the conversation that circles the tenuous connection between the created and the creator, providing inspiring insight on how poetry, technology, and the automaton can function as a sensory appendage.

“Power On” is Ko’s curated gallery of automatons — humanoid projections that she fabricates to fuse technological advancements within the core of humanity. This bond that Ko weaves together through the collection allows the reader to situate themselves at the core of this relationship. The question of the future is framed explicitly, and also quite literally. Ko frames the white space on the page with left-aligned and right-aligned pages, giving the reader plenty of room to project themselves into the book. This is key to understanding Ko’s project. The experiment ensnares the reader into the conflict and pastes them directly onto the page.

That is the core beauty of Ko’s collection. The entire book is an experiment in conflation. Ko tethers together concepts, ideas, people, and machines to facilitate a space that breeds immersion. The coalescence that interlaces the poems also pulls together a god (dead or not) to humanity, humanity to the machine, and the reader to the speaker.

The unheard can be represented or attributed to a variety of sources. The unborn speaker from several poems scattered throughout the collection provides a solidly reflective or introspective angle to an otherwise perilous exploration. The moment humanizes the subjects of the poems. As the reader, it is impossible not to step back and consider the automatons acting in Ko’s collection as figures with a core of humanity. The automaton is a machine striving to imitate its creator, similar to the way humans intend to imitate a god. When created in the image of the self, the creation tends to resemble its origin, and Ko makes this abundantly clear.

When discussing the emotional capacity of the automaton, Ko writes that “if our machines also possess the human desires for connection and love, then they may turn out to be the frightened and frightening figures that appear in POWER ON.” There is valuable involvement that gives technology the human power of subjectivity to a creation plagued by objectivity. Ko’s collection peels the guise of objectivity from technology; from the automaton, and reveals something pure that mirrors her view of humanity. The automaton becomes the frightened extremity of humanity, powering on regardless of what there is to fear; connected to both self and creator. There is an inherent dialogue that Ko curates, allowing for conversations that have been relatively unheard to finally be broadcast.

“The type of powering on that I advocate for in my project is one that encourages respite from urgency and disorder; it is an accommodated empowerment,” Ko writes regarding her process. This book is a collective effort, founded on the dialogue between the poem and reader that is perpetuated by this connection.

Ko’s project extends from the page, broadening its sense and its range. The poet intends to suspend poetry from the restrictions of the page and allow for readers to take control of the text. The “Power On” app available on both the iPhone App Store and the Android App Store will allow readers to contribute to the text. Ko perfects her book’s missions through this multi-medium, multi-perspective approach. She materializes the core of “Power On” by allowing the conversation to take place between readers among machines and humanity. This encourages an intervention, forcing readers to come to terms with our technological appendages. Ko reflects the physicality of the book, multiplied across the matrix.

“Readers can also bend or break the spine of the book, crease the pages, write notes on the pages, pass the book onto others, or store the book for keeping on a shelf,” Ko writes. “And how we incorporate the content of the book into our lives is also dependent on an entire matrix of identity factors that first allow readers to arrive at the book, facing the book and its content.”