A look at faculty diversity

By Eunsong Angela Kim & Anida Yoeu Ali

While at SAIC, we have begun to count; to count the number of courses in post-colonial or critical cultural studies; to count the number of times a seminar class begins without referencing white men as if they are the center of critical theory and practice; to count the number of females or persons of color that are taught in our classrooms, are assigned in our syllabi, or are referenced in lectures.

Outside or “rogue” counting happens when a system that promises unbiased standards and checks fails. Whether one has benefited or been marginalized by these standards is irrelevant.

Whether accidental or not, discriminatory practices/standards/checks are a sign of corruption and the failure of a system that is supposed to help structure the lives and learning experiences of those within that system.

For our own rogue counting at SAIC, we looked to reporting by Jenna Sauers on the feminist website, Jezebel, for inspiration. For the past two years, the former model-turned-journalist has counted the number of models of color who appear on fashion runways.

Her reporting lists the designers who used models of color, the designers who didn’t, and most importantly (accordingy to her and interested insiders) the designers who used only one.

When Sauers first began to count, she did so under a pseudonym. She retired some months later to reveal who she was, and continues to actively write for Jezebel.

Whether or not models, fashion, runways, and the like should exist is not the point. Jenna Sauers counted to hold her industry accountable for its employment standards.

We acknowledge that it is easier to point out the flaws of an institution than its positive aspects, but after two years of graduate school here at SAIC, we felt that it was important to address the lack of accountability for diverse representation within the faculty and staff.

The point of this article is not to direct the flames of our anger and disappointment at the school — the point is that these numbers do count. However, if you are part of a marginalized group of people, visibility and the proper allocation of resources will always matter.

Our goal is to push for a more transparent process in the school’s hiring and recruiting practices (because the student body cares), and the kind of academic classes, scholarly discourses and education SAIC continues to promote.

Coming from public institutions for undergraduate school, we were frustrated to find that the statistics were difficult to uncover — SAIC has only recently posted the figures for student diversity on their website, buried in the “Enrollment” link in the “History” tab of the “About SAIC” section.

The numbers for faculty are available — through contacting James Britt in Multi-Cultural Affairs and other administrators — but getting them should definitely not feel like such a maze.

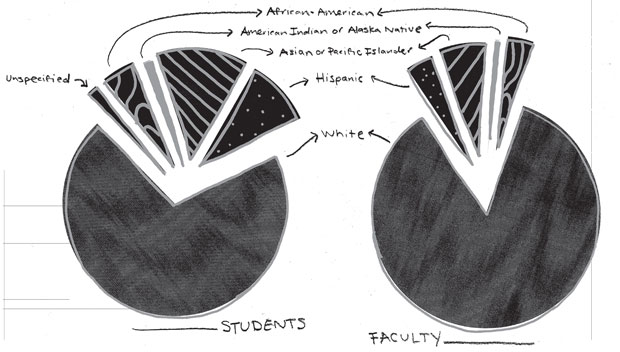

As of Fall 2009, the SAIC student body is 67% female and 33% male, with 17% of the population representing 46 countries outside the U.S.

Asian-Americans and persons of Pacific Island decent make up 11% of the school’s student population; 8% are Hispanic; 4% are African-American students; 1% are American Indian or Alaska Native; and 1% chose not to identify their race/etnicity.

This means that less than 24% of the school is made up of people of color, not including the international population. White students still make up 58% of the school’s non-international student population. These numbers almost indicate that SAIC has done a proficient job at recruiting students of color.

The full-time professors at our institution, and therefore the school’s hiring practices, do not reflect the student body. There are eight black male professors and two black female professors who are either full, associate or assistant professors, in addition to four male and three female Hispanic professors, and seven male and three female Asian professors in these positions. There are 70 white male professors at SAIC, and 53 white female professors in these positions.

We think it is also important to point out that though there is a large Korean community on campus, there are no Korean or Korean-American professors, and that many of the Asian Professors do not teach “art.” Most Korean faculty are in adjunct positions, and a few of these do teach art courses.

There is also a sizable Hispanic community at our school, which is also not reflected in our full-time faculty, and there is only one Hispanic adjunct professor at the school.

To be clear, Hispanic students make up eight percent of our school — while Hispanic faculty make up four percent. Asian-American and Asian International students make up nearly 20% of our school, while only comprising six percent of the faculty. Interestingly enough, Black students make up four percent of the school while comprising six percent of the faculty.

In examining these numbers, we had to wonder, exactly what are the diversity commitments at SAIC and how are they implemented?

Though we have not included all the statistics here, it should be noted that there isn’t a great number of adjunct faculty of color at our school. The terminology can be confusing but for many teaching faculty (and students), the labels “Instructor” and “Adjunct” do not include power, academic growth and support and stability.

We are concerned that this institution is still unsure of the merits of these individuals as professors, and that they can be let go with relative ease if need be. This is in no way to dismiss the personal value of adjunct professors but to criticize OUR school for devaluing so many of OUR professors, especially our non-tenured female professors and professors of color, and other marginalized individuals and groups.

From what we understand, a process has begun to hire full-time tenure-track professors for Contemporary Practices (formerly First Year Program). As evidence of the school’s lack of transparency, one must look really hard as only a few leaflets are posted, announcing these candidates and their lectures.

Our rogue counting on this subject (internet research and some interviewing) indicates that of the 16 finalists, none are people of color and none come with experience in post-colonial or critical cultural studies.

It is our experience that one is a token and two is never enough — especially considering the student body population and the lack of diversity in the current faculty population.

We were motivated to write this article because we do not feel issues of diversity in the faculty are discussed enough. And because when we did first address these concerns, they were labeled as “suspicions” by our professors.

If the School does not readily provide clear, up-to-date, and accessible information about the institution, then the School is encouraging an environment of gossip and suspicion.

When information is not easily available, it becomes difficult to even know what to complain about. We believe that it is our right to have access to this information.

We do understand that being women of color and aggressive about our political beliefs will always make things seem personal. We will never be able to be politically angry without first excusing and acknowledging the fact that we, or individuals in positions close to us, will benefit from such demands.

We will always have to apologize for wanting our political concerns to be included in the list of concerns because they will be interpreted not as a demand for systematic and political change, but as a demand for us, or more of us.

High art, art, ART, films and more are still very white, very male. So then what is SAIC saying? Is it preparing us for reality? Or is it participating in and solidifying the lazy norms of this very small world?