For the film’s first 20 minutes, all you know is that you’re going to be spending time with a young woman of indeterminate age, who shows up at parties, and occasionally has something like a good time. She’s charming, if a little green. You see something of yourself in her: the part of you trying for a serious conversation in a festive atmosphere, the part that isn’t sure whether you deserve the attention but wants it anyway. A story is told, though it takes a little while to reveal itself.

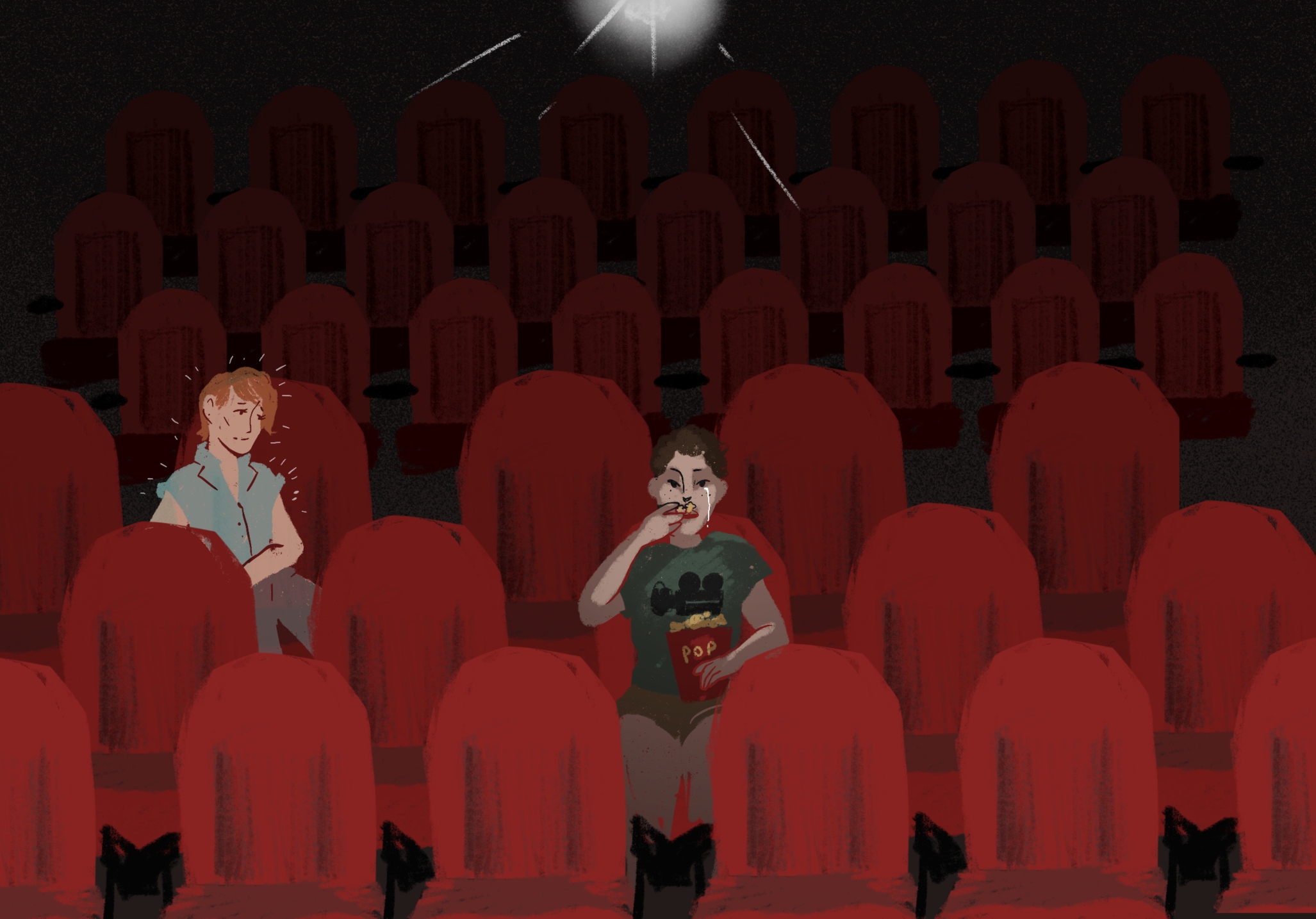

There’s the question of a film. She wants to make one, and she’s deeply invested in it being good, important, something that gets at the essence of interpersonal relationships. This is more or less what the audience hopes for too, when attending a film like “The Souvenir;” she’s therefore speaking in front of us (onscreen), but also to us, and for us. You realize — if you care about such things — that “The Souvenir” is going to be a self-conscious film. It would like to give the impression that it’s in the seat beside you, watching itself, critiquing itself.

There’s the event of a relationship. It gathers momentum slowly — a platonic connection developing. She explains her film idea to a man at a party. Shortly thereafter, they meet for tea in a fancy place. He shows her a painting, explaining that its female subject is in the throes of new love. She agrees. He asks to stay at her place for a few days. She assents. There’s a touching exchange where they bicker over who has more space in bed. It doesn’t turn sexual. He pursues the inquiry beyond the scope of a mere space negotiation, but she’s game for it, and you find yourself grinning. You’ve been through something like this, and it was nice.

He leaves for Paris and comes back with a slender pink box. He places it on her bed, then instructs her to put its contents on, and she does. It’s a negligee. They make love. In the morning, she identifies strange markings on his inner elbow. He professes ignorance, but says that they’re sore. She says he should just let them go away naturally.

A few minutes later, the words “habitual heroin user” are uttered at a small dinner party, hosted by a filmmaker friend of his. Suddenly, we know what we’re dealing with.

The narrative insecurity is resolved — not a moment too soon, and not a moment too late. The film, which has thus far proceeded as a curious if not deeply urgent sequence of events, has exposed its central conflict: He’s a drug addict, and she’s susceptible.

What happens next is more predictable, though no less painful. He spins out of control, and she tries to stand by him. He represents something idyllic — a man of quiet mystery, someone who understands her, and who has an elevated idea of her. He starts asking for money, and she starts giving it to him. She starts asking her parents for loans, and then keeps asking her parents for loans, pleading a need for more film equipment. She becomes pale, tired, and ineffective on set at her film school. She’s devoted to proving her loyalty to a man disloyal to everything except his drug. He steals her stuff — her film equipment, some prized possessions — and explains to her that he had to do it, lest he be subsumed by chaos. She apologizes.

This all happens slowly. Takes are long, conversations happen in a low register, extreme opinions are articulated dispassionately. The filmmaking motif recurs in a somewhat navel-gazey way — a shout out to the filmmakers in the audience, who are as committed to proving the “film = life” theorem as they are to taking in the story. Her evolution as a filmmaker mirrors her development into adulthood, and I think we’re to intuit that the director of “The Souvenir” is as attached to this subject matter as their characters are attached to bad habits. The act of filmmaking is put on something of a pedestal. If you’re a filmmaker, I’m sure there’s a tremendous resonance. If you’re some other kind of creative, you get it, though you maintain fealty to your own medium. If you’re no kind of creative, the motif might feel perfunctory.

“The Souvenir” climaxes in tragedy. He exits her life, irrevocably, and she grieves. At the last, she’s directing a scene — quite well, we understand. The set is silent except for a soliloquy. The take ends, she looks into camera (not her camera, but the God camera, the one we’re on the other side of), a big door opens, darkness is flooded with soggy English light. She walks out into it. She has loved, suffered, lost, and created, and now she’s stepping beyond the threshold. What threshold? Between adolescence and adulthood? Past the edge of grief? From looking at Art to creating it? From the mortal realm to a realm beyond? Sure.

And what exactly is the souvenir? The long, many-buttoned black coat he leaves behind, which she cradles once she’s heard the news? The film she creates in the aftermath? The scars love makes on those who try? Her own life, continuing in his life’s — their love’s — absence? Her mother who loves her with more heartbreaking urgency than he ever dreamed of? Sure.

This film will make you hurt, and then it will make you think. It’s quiet, and deliberate, and stylized, so pay attention. You’ll consider your mother, and the misguided love you lived for in your youth. You’ll hope that, beyond the wall, she associates with forces that have her best interests in mind. You won’t know whether she will.