Horror has been crawling towards postmodernism with the same listless enthusiasm of a disemboweled zombie. With few exceptions, the genre has seemed content to rehash the same tired tricks, repetitive motifs, and predictable twists. In July, the trailer for a gruesome and gorgeous Austrian film called “Goodnight Mommy” (2014) was released and tantalized more than 7 million viewers with its prospect of something new. Featuring stunning, saturated shots of the Austrian countryside and horrifying images of a silent woman with a bandaged face interacting with her twin sons, the trailer seemed to present an unfamiliar plot and an original antagonist. However, when “Goodnight Mommy” saw a US theatrical release this September, the film’s promised breath of fresh air turned sour. “Goodnight Mommy” merely performed mouth-to-mouth on the corpses of overdone horror tropes.

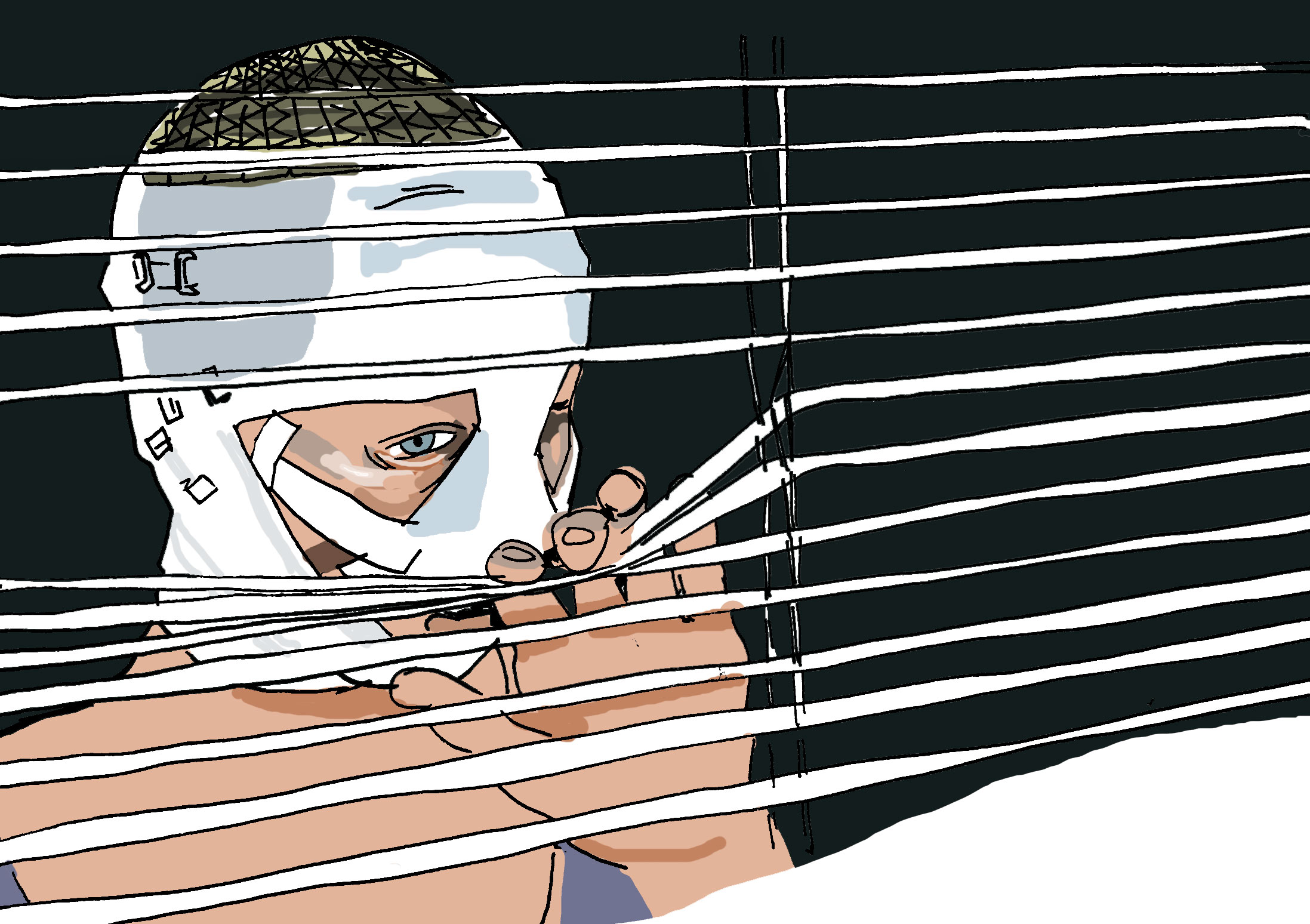

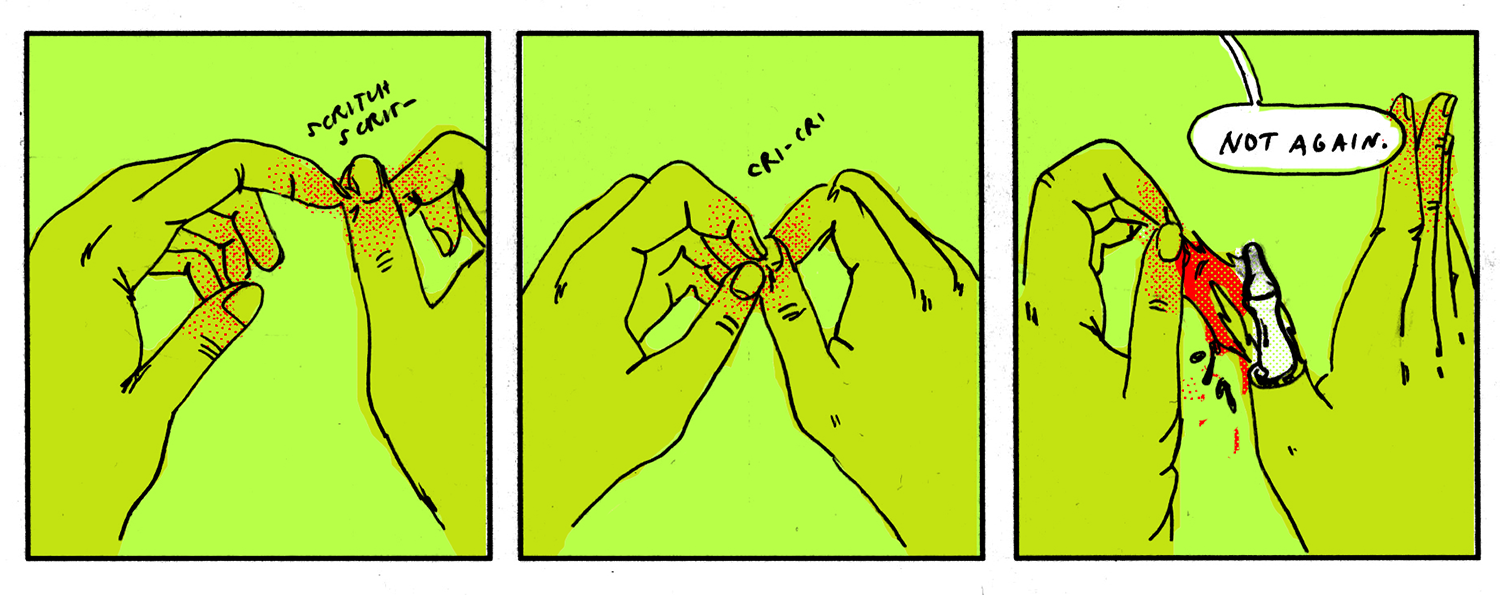

Written and directed by Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, “Goodnight Mommy” is centers on a mother recovering from a recent plastic surgery and her relationship with her twin 9-year-old boys, Elias and Lukas. It is summertime, and the boys spend much of their time jumping on a trampoline or wandering through fields while their mother lurks indoors. Soon, however, things take a more sinister turn. The mother will only acknowledge Elias and pretends like Lukas does not exist; the boys become convinced that the bandaged woman is not their mother. After some skin-crawling scenes — the boys play with pet cockroaches; the mother strips naked and her head spins in the woods; the boys explore a decrepit tomb — the twins tie the woman to her bed and begin to horrendously torture her. Ultimately, they burn their mother alive.

Fans of horror will pick up on common tropes of the genre from this synopsis alone. Audiences that grew up in the heyday of Haley Joel Osment (the ones who ran around during middle school recess whispering, “I see dead people”) will immediately take the mother’s deliberate avoidance of one twin, Lukas, as a sure sign that he is dead. You can’t pull a he-was-dead-the-whole-time! over on the “Sixth Sense” generation: M. Night Shyamalan has been conditioning us to expect grandiose plot twists since 1999. Creepy twins? We’ve seen “The Shining” (1980). And although “Goodnight Mommy” tries to manipulate its audience into an emotional allegiance with the young boys, we’ve been on the look-out for secretly evil children since they found that “666” on Damien’s skull in “The Omen” (1976).

Today’s horror fans have seen the classics and horror conventions have permeated pop culture. Filmmakers should use this to their advantage. Imagine a character answering the ringing “Evil Phone” and then have the call not be coming from inside the house. To be postmodern.

If you need a primer on “po-mo-ism,” Mike Rugnetta of the PBS Idea Channel, a popular YouTube series, gives an excellent crash course in postmodernism through a discussion of the cult television show “Community.” “Referring to visual art, literature, philosophy, film, architecture, music, the postmodern condition describes a skeptical, often playful response to established concepts,” Rugnetta explains in the video. “Many postmodern works are built on reference, pastiche, genre agnosticism, and not so much the betrayal of expectations, but the question of whether expectations are even important in the first place … They are self-consciously referential, skeptical, and playfully judgmental of culture.”

Maybe this tendency for postmodernism to manifest as “playful” is why only horror’s close cousin — the horror satire — has made the comedic postmodern leap.

Horror satire is not new: an early example is Wes Craven’s “Scream,” which came out in 1996. “Scream” had its characters literally say the rules of a horror movie — don’t have sex, never say “I’ll be right back” — before proceeding to kill every dumb teenager that broke them.

When “Cabin in the Woods” came out in 2013, I thought the blood-filled tides were turning towards postmodernity for all horror films, but it seems Joss Whedon’s masterpiece only encouraged the creation of more horror satire. In October, “The Final Girls” was released, which sees its Scooby Gang of characters magically transported into an ‘80s slasher film. As the title suggests, the 20-somethings — just like modern audiences — have seen enough horror films to know what to expect: horror’s persistent habit of offing every character that has sex, and leaving only a virginal “final girl” to slay the crazed killer and survive. The movie uses the audience’s knowledge of horror tropes — “everyone who has sex in this movie dies!” — to get laughs and craft a truly original story. Imagine what real psychological damage horror could do with the tropes horror satire so masterfully manipulates.

Postmodernism is a toolbox, and it is filled with concepts and brain-benders that horror filmmakers could use to make movies that are more than skin-and-bones plot with a few jump-scares. “Goodnight Mommy” proves its genre’s need for a pinch of the postmodern. Audiences expect the film’s half-committal, is-it-or-isn’t-it dream sequences and “big reveal” twists. From the moment the film begins, viewers know that the twins are evil, one is dead, and that the film will end with an eternal “goodnight” for “mommy.”

But the twins aren’t Evil – Elias is traumatised. As is the mother. And this trauma makes them behave inhumanly towards each other. The story is more tragedy than horror, really.

Welcome to the wonderful world of snide arrogant post modernism which seeks to make sure that you understand that nothing in life is valuable. But without a story which affirms values of some kind, what is the point of watching the film in question?