Will the MCA’s New Restaurant Diversify Its Audience?

When it comes to museums and public spaces, how do you define “accessible”? Entrances equipped with ramps for wheelchair users, texts on gallery walls in braille for the blind, free tickets for younger people, seniors, and unemployed citizens, unpretentious public programs that make everyone feel welcome? The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (MCA) recently announced, under the banner of accessibility, that it will have a new restaurant.

On February 20, Madeleine Grynsztejn, the MCA’s director, announced the launch of a $64 million fundraising campaign called the Vision Campaign, dedicated to “support the MCA’s highly acclaimed programming renowned for engaging audiences with the most important art and ideas being produced today.” The museum has already raised $60 million in private donations for the fund, including gifts of $10 million from Helen and Sam Zell, Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson, and Kenneth Griffin. Each gift represents 216 times the median annual income of a Chicago household, members of which are potential new visitors for this more accessible MCA in the making. Will they enjoy the idea of spending an extra $100 for a family lunch in addition to the $12 museum admission?

Vision Campaign funds are not all going to the construction of the restaurant. During the press preview of the Doris Salcedo exhibition on February 21, Grynsztejn explained that the Kenneth C. Griffin Charitable Fund’s donation will go toward the creation of the Griffin Galleries of Contemporary Art, adding that parts of the fund will serve to create new educational facilities. Grynsztejn compared the MCA to millennials, also known as the slash generation, “those twenty-somethings who are psychiatrist/DJ, researcher/baker, coacher/singer.” The MCA has sought since its creation to blur the lines between disciplines and offer a plurality of activities. She mentioned the museum’s dedication to the artists it exhibits and said that now could be a good time to respond to its audience. “Our ruminations have brought us to the point where we are ready to literally physically embody our ideas about a new kind of accessible museum,” she said before announcing their revolutionary strategy to accomplish this.

The MCA contracted L.A.-based architectural firm Johnston Marklee to develop a master plan for the new museum including the new restaurant to open in May 2016. Johnston Marklee is behind the fashion boutiques of Maison Martin Margiela in Beverly Hills and the Menil Drawing Institute in Houston Texas. The museum also hired, or as Grynsztejn put it, started a new creative partnership with Mevis & Van Deursen, a cutting-edge graphic design firm based in Amsterdam. Some may wonder why a Chicago-based artistic institution would not choose from among the many local architecture and design firms rife with talent in their own back yard. Is this also in the name of accessibility?

Mevis & Van Deursen created a new visual identity for the MCA that Grynsztejn said is “exciting” and “embodies the museum’s goals for access.” It will convey that the museum is playful, welcoming, smart, and open. The MCA staff described the collaboration with Mevis & Van Deursen as “essential to creating an accessible and powerful visual identity.” What does an “accessible visual identity” look like? We have to wait until the public launch in July to find out.

Both in the press conference and the press release, the MCA focused heavily on the new restaurant, giving little information about the educational facilities to be built. F Newsmagazine reached out to the MCA for a comment with no reply. It is certain that this educational area — currently being called “the engagement zone” — will be located where the museum’s café is now. “We plan to make a space that will completely redefine the concept of a museum education center where visitors and artists share a welcoming place to learn, to linger, and to discover art and creativity,” said Grynsztejn, but she did not say how the MCA plans to do it.

Many museums in the past have used traditional tools to create engagement opportunities for new audiences and become more accessible museums. Some may have decided to create partnerships with existing local and community organizations. Cool Culture, for instance, is a New York-based non-profit helping low-income families accessing cultural institutions in New York for free. Other museums, such as the Yale Center for British Art, have developed specific public programs for families with children on the autism spectrum. Institutions such as the Dallas Museum of Art have decided to increase their accessibility by doing away with admission fees completely.

None of these is the accessibility trailblazer that the MCA seems to be with its new restaurant. “We’re all excited to think together about how a new restaurant can serve the MCA’s vision of being a welcoming space that is a portal to art, social experiences, the creative process, and of course, great food,” said Grynsztejn. With their audience in mind, the MCA is hoping to “[increase] the museum’s relevance and reputation while broadening [our] visitor base.” It seems the MCA has realized that the most valuable Chicago audience are tourists (as the city’s Cultural Plan makes apparent), and it is now doing its best to become more accessible to overlooked communities of demanding palates and people with full wallets.

The MCA has undeniably high-quality and multidisciplinary programs. Its dance performances, for instance, never disappoint. Mariano Pensotti’s Cineastas was one of the most exciting Chicago premieres of a great work of theatre in 2014. The Doris Salcedo exhibition currently on view has reconciled more than one person with the MCA’s treatment of Latin American art, especially following the opportunistic Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo. It is a shame that the MCA’s audience is not as broad and diverse as its programming.

The MCA does a lot for artists. It feels like a safe and exciting place to be invited as an emerging or established artist. Its Chicago Works series, a recurring program showcasing the works of Chicago natives, is a wonderful springboard for artists and a great opportunity for audiences to discover local makers. South Shore resident Faheem Majeed is now part of this series, and his civically engaged practice and involvement with South Side communities could be a wonderful opportunity for an overlooked audience to feel welcome at the MCA.

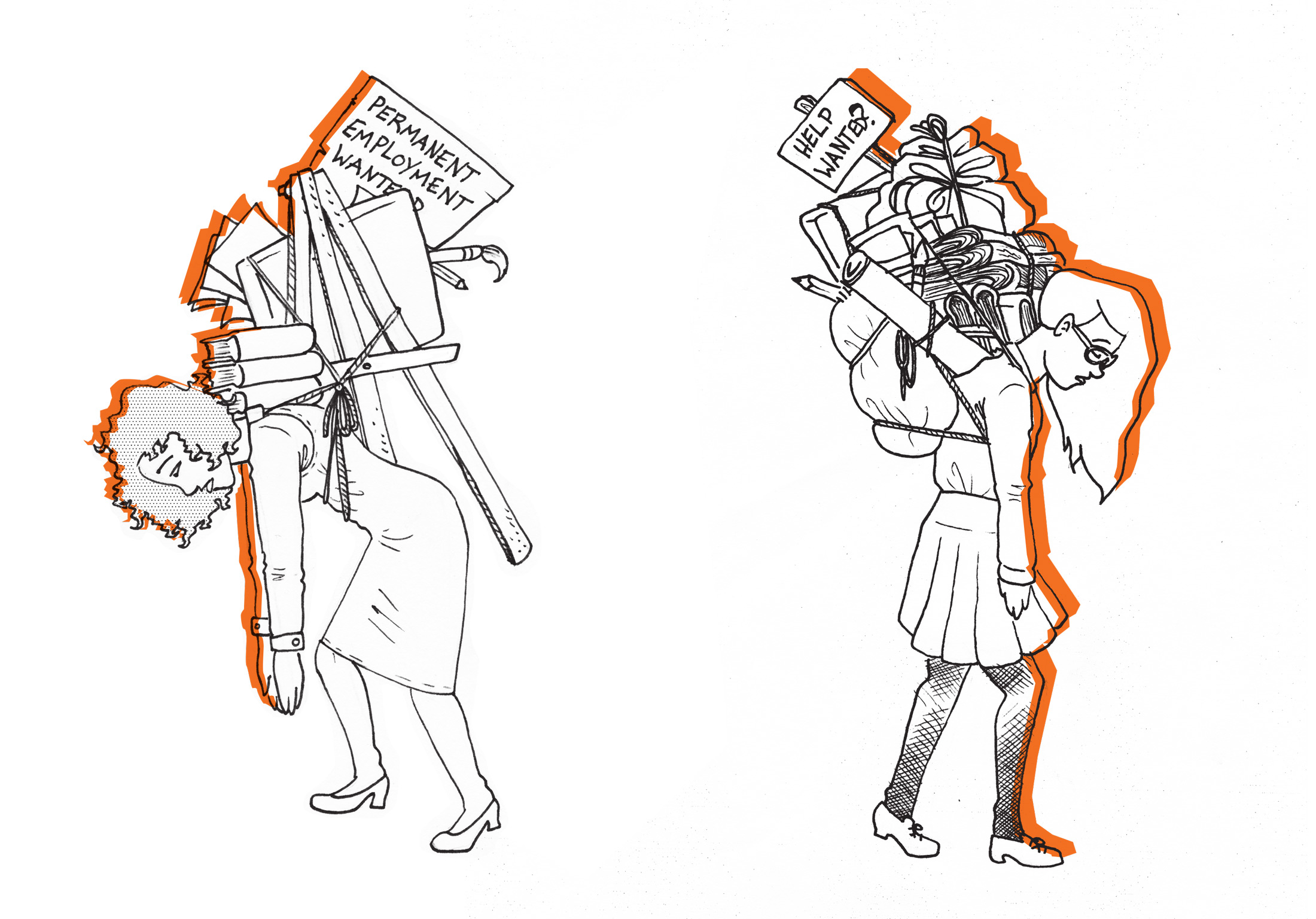

It is unfortunate that a brand new restaurant is the MCA’s most promoted tactic for creating a more accessible museum, because one must wonder whether the true motivation for the Vision Campaign is the museum’s reputation. It is okay for a museum to want to build its reputation as an institution, to host blockbuster exhibitions, and to have a fancy restaurant. It takes all kinds of museums to make up an art world. It is not okay to talk about accessibility when what is being most promoted will likely only recreate existing power dynamics in the arts. People who do not have the social and financial means to access museums probably do not have the means to access restaurants either.