Sunset (Atardecer), 2003, by Alexandre Arrechea

What does new media art look like in a place where access to new technologies and the internet are strongly restricted? The show Cuban Virtualities, displayed in the Sullivan Galleries from December 2 to February 14, exhibited a collection of Cuban New Media artists who examine the function of technology within a local context and their personal relation to an external globalized world.

Originally exhibited at Tufts University Art Gallery and curated by Liz Munsell, the Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, as well as the artist Rewell Altunaga, the show was brought to The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and organized by graduate students Gibran Villalobos and Will Ruggiero.

During a panel discussion on February 10, Munsell explained the difficulties of curating a show hampered by the unresolved hostile political relationships between the United States and Cuba. Because often artists were prevented from traveling outside the island, the show had to be organized via an “endless chain of emails” that Munsell called a “prolonged chat format.”

Before entering the gallery, viewers had the opportunity to read small boxes of text on a timeline that presented an overview of the Cuban dictatorship and its toll on the availability of technology.

As the United States experienced a proliferation of technological development, the Castro regime held a tight grip on digital resources and prohibited the use of devices to spread information such as cell phones until 2008.

These types of challenges characterize a new media artist’s practice in Cuba, which is heavily influenced by what Munsell calls a technological scarcity. Rather than impeding the artist’s creative output, Munsell says that the scarcity mentality forced artists to engage with their materials in a more creative fashion.

A variety of installation methods were used throughout the gallery from single video pieces displayed on television monitors to multiple digital projections, each of which required different levels of interactivity but addressed similar themes.

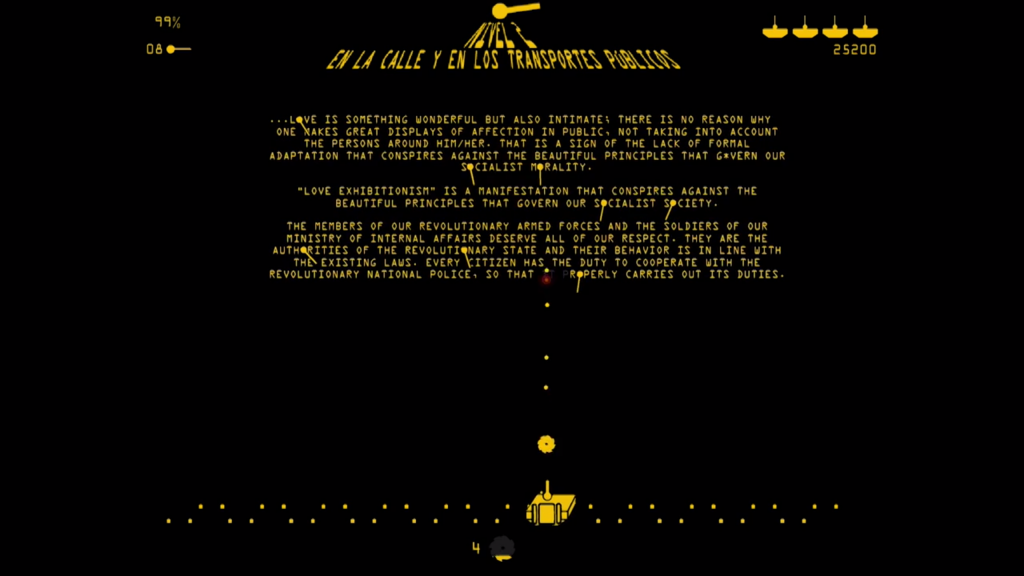

Rodolfo Peraza’s video game titled Play and Learn 2.0 (Juega y Aprende) instructed viewers to engage in a virtual quest that investigated the role of institutionalized norms and belief systems in shaping individual minds. Peraza uses his experience as a second grader reading the Cuban textbook The Handbook of Formal Education as a reference for the design of the game.

The game’s aesthetic quality compares directly to arcade games from the ’80s such as Space Invaders, but is recontextualized through the act of destroying iconic figures like Che Guevara, José Marti and Vladimir Lenin.

The Falling Man, an eight minute and fifty second video loop by Rewell Atunaga, presents the perspective of a man falling from one of the Twin Towers on September 11. The constant change in perspective as the man spirals downward is a disorienting virtual experience and confronts the audience with technology’s dissociative elements and its potential to cause personal disconnect through platforms like social media.

The video installation by Celia González Álvarez and Yunior Aguiar Perdomo, faceloop, uses the logic of Facebook’s networking function and applies it to real-time human contact. During their residency in Scotland, the artists met and were introduced to people around the town. Along the way the artists documented where each person lived and used this data to visualize their encounters. A web of these interactions was projected in the gallery and began with one point of origin, but as the artists continued to network, multiple lines continued to further travel outward. Surrounding the dense map were photos of the people the artists met as they continued to make acquaintances.

Susana Pilar Delahante Matienzo explores the difference between physical presence and virtual presence in her interactive piece Mirror of Patience. During the limited periods when the artist had access to the internet she was present in the gallery through a video projection where she played patty cake with the audience and even started conversation with the viewers.

Variations on these themes are explored throughout the other works in the gallery space. Ultimately, there is a sense of isolation emanating from those interactive works as they address issues of virtual and physical presence, as well as the individual’s relationship with technology.

Munsell remarked that a type of “double critique” occurs within the gallery space, where it is “not just a critique of scarcity or lack of access to technologies,” but also comments on the functioning of the technology itself by “reflecting on local situations” and then “projecting their interpretations of technology” outward.

Although at least half of the Cuban artists featured in the show now live abroad, their work continues to focus on genuine overcoming of physical isolation. Through their digitally interactive works, they have managed to connect with an audience living in a remote national, social and political context. As international relationships with Cuba change, the artistic process and concerns of the Cuban Virtualities artists might experience their own revolution.