When uncertainty is the only thing to be sure of

by Maureen Clare Murphy (a former editor of F Newsmagazine who is currently living in Ramallah.)

Sometimes there are dozens of people pushing to get through the sex-segregated lines at the Qalandiya military checkpoint between Ramallah and Jerusalem. And sometimes it’s just a handful of people, waiting to have their IDs and belongings checked by the young Israeli soldiers manning the checkpoint. Sometimes passing through the checkpoint can take over an hour, sometimes just a few minutes. I have found that it is this arbitrariness, and unpredictability, that pervades all aspects of life since I moved to the Israeli-occupied West Bank nine months ago.

”You don’t know what [the Israelis] are thinking. You never know,” says T., one of the merchants who have set up shop around the checkpoint, laying cheap costume jewelry on top of a piece of cardboard. I am interviewing him for a story I’m doing on the multi-million dollar checkpoint the Israelis are building on the lot they razed just next to the current checkpoint, one of the hundreds of checkpoints, road blocks, barriers, and other means of Israeli-imposed movement restrictions in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The Israelis are doing a lot of work around Qalandiya, southeast of Ramallah. Not only is the new military checkpoint being erected—far more permanent and expensive in appearance than the current one that was built a few years ago—but we are also witnessing the building of a concrete wall stretching from the southwest edge of Ramallah, to be met with the wall coming up north from Jerusalem, cutting off Ramallah from its holy sister city. People are waiting to see how all these new structures will affect their lives.

My former colleague N. has the very Palestinian ability to laugh at the most stressful times, but her tired voice lowers one day when she tells me, “Who knows what will happen. Maybe we’ll get divorced.” We’re discussing the problems she has had because she has a blue East Jerusalem ID and her husband has a green West Bank ID. (Under international law, East Jerusalem is part of the West Bank, but Israel illegally annexed East Jerusalem in 1967. The rest of the West Bank, as well as the Gaza Strip, have been under Israeli military occupation since then.)

Because of the differing colors of their IDs, N.’s husband can’t live in, or even travel to, East Jerusalem and their only option is for N. to live in Ramallah. However, she is in constant danger of losing her coveted blue ID because she resides in Ramallah, and Palestinians with blue IDs (as they are stateless, Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza Strip don’t have passports) must prove that Jerusalem is the center of their lives. This is a very difficult and costly endeavor for Jerusalemites residing elsewhere in the West Bank, as they have to prove ownership of property to keep their IDs.

Should N. lose her blue ID, she may never again see her hospitalized mother, and would face extreme difficulty in seeing the rest of her Jerusalemite family. But what she’s most worried about is her teenage son. N., like many others here, fears that an even more intense and bloody conflict will soon develop because the humanitarian and political situations are so untenable, and are only going from bad to worse.

She figures that there is no good future here for her son: either he will be physically harmed or arrested by Israelis (the majority of adult Palestinian males have been detained in Israeli prison at some point in their lives), or he will be pressured into joining a Palestinian political faction, increasing his chances of being hurt or detained. At the risk of being considered a traitor to the national cause, N. wants to move her family to Canada.

Another former colleague, Z., is an example of how no young male, no matter how clean, is immune from arbitrary arrest by Israeli forces. Z. was handcuffed at Qalandiya checkpoint as he was making his way home from class at Birzeit University, where he is a candidate for a Master’s degree in sociology. He has been incarcerated ever since, leaving his wife without her husband and breadwinner, and their two small children without their father.

I know Z. from my time as an intern with a Palestinian human rights organization with which Z. is a fieldworker. His job is to document human rights abuses committed in the Bethlehem area. It takes a strong will to do the depressing work he does. He also travels twice a week to the university—a journey which clocks in at three hours each way because of all the Byzantine road closures—leaving me to think that Z. couldn’t possibly have time to even consider committing a crime between working, studying, and being a father and husband.

Z. has never been charged with any offense, and probably never will be. Israel holds hundreds of men, and a handful of women, in what is called administrative detention. Administrative detainees are held in indefinitely-renewable six month terms. Often the Israelis simply say that they have a “secret file” on a person, but such files can’t be accessed, even by detainees’ lawyers. There are hundreds of prisoners, and thousands more Palestinian men who have served time in the past, but whom have never been charged, granted a trial, or shown the information stored in their files.

Unfortunately, both Z. and N.’s stories are drops in the ocean of tales of injustice claimed by Palestinians in the occupied territories. Stop anyone in the street and they can give you an example of how they were personally affected by Israeli violence, collective punishment, arbitrary arrest, and myriad other human rights violations that Palestinians endure on a daily basis.

Of course, like Palestinians, Israelis suffer from the psychological hardship of not knowing—they too have major uncertainties, such as, will they become a statistic thanks to a suicide bomber, or will their children who, are conscripted into the army at the age of 18, be harmed while serving? But the difference in the quality of life between Israelis and Palestinians is stark, and the balance of power between the two is extreme.

During the Palestinian presidential elections last January, I served as an election observer in the Hebron area. The day before the election, I happened to be at the Qalandiya checkpoint when then-candidate Mahmoud Abbas rolled up in his shiny black Mercedes. Even his movement, like the average Palestinians queued up at the checkpoint, was under the control of a young pony-tailed Israeli soldier.

Like many of my Palestinian friends who didn’t vote, or who cast blank ballots in protest, I thought afterwards to myself that the concept of having “free and fair” national elections under foreign military occupation was a joke, especially here where there isn’t even a state, and whoever wins the election will have little power yet take all the blame for whatever goes wrong. But as in American-occupied Iraq, Palestinians were made to prove to the Western world their capability of putting a ballot in a box. It seems that neither place has enjoyed any fruits from such “democracy.”

On election day, I traveled around the Hebron area with another human rights fieldworker and his eldest daughter, who was just shy of the 18-year-old age requirement for voting. As we were outside her dilapidated school where a polling station was set up, S., who happens to be the chess champion of Palestine in her age group, said that when the Israelis next invade her village, she hopes that they will destroy the school.

When we got inside the school, I understood her bitterness. Even on that sunny day, the winter cold was biting, and there was no heating in the school. The lack of insulation means that it is probably unbearably hot in the summer. S. tells me that during winter, students wear gloves in the classrooms and have a hard time concentrating because of the cold. The dim lighting doesn’t help. The classrooms are overcrowded, and the curriculum is cut to a bare minimum due to a lack of both money and time (children can’t make it to school when Israelis declare a curfew, and the Hebron area has been subjected to more hours of curfew than any other area—5,828 hours between June 2002 and September 2004 alone).

I wonder what kind of opportunities a brilliant student like S. would have enjoyed had she grown up in a healthier environment. As we left the classroom, S. pointed out to me the martyr poster of her 16-year-old cousin, killed by Israeli soldiers, hanging over the blackboard.

The next day I spent playing card games with S. and her four younger siblings, all of them precocious young chess masters with unlimited confidence, thanks to their incredible parents. I taught them how to play American Rummy, and by the end of the day the students were about to beat their master. In their game-loving household, they jokingly call their father “America” because he always wins at chess. They have a far better understanding of world politics than I did at their age.

It is the future of the young people of Palestine that worries me the most. They grow up in a situation where extreme conditions—such as military checkpoints, curfew, and losing loved ones to violence or Israeli prisons—are the norm. Their parents’ authority is negated when they witness how powerless Palestinian adults are when passing through Israeli checkpoints. A popular game amongst kids here is “Israelis and Palestinians,” the Middle East’s answer to “Cowboys and Indians.” Kids fight over getting to be the powerful Israelis, because the weak Palestinians always lose.

It’s hard to be hopeful for their future. A young man who strikes up a conversation with me and some of my other foreign girlfriends in a public taxi in Ramallah becomes excited when I tell him I’m from Chicago. In Arabic, he explains that his brothers are living in Chicago, though he has never visited. His mom says he must stay here, “fi il balaadna”—in our land. “Mumkin fil mustaqbal”—maybe in the future—he will visit Chicago, I say. “Fish fii mustaqbal hon”—here, there is no future—he replies. I can only wish that he will be wrong.

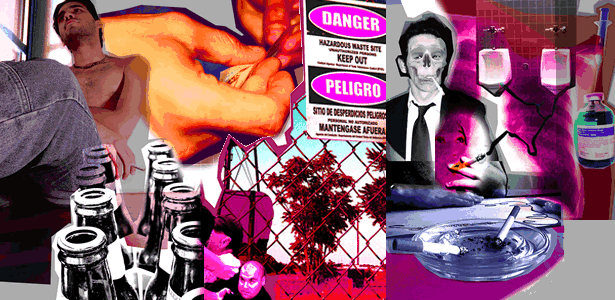

Photo by Maureen Clare Murphy

September 2005