The Art of Edward Gorey at LUMA

In February, the Loyola University Museum of Art (LUMA) opened an exhibition of the work of Edward Gorey, the Chicago-born author and illustrator known for his playfully dark drawings and verse. The show — which technically encompasses two different exhibitions entitled Elegant Enigmas: The Art of Edward Gorey and G is for Gorey, C is for Chicago: The Collection of Thomas Michalak, respectively — surveys the artist’s prolific career that spans 50 years, 90 authored books, 60 illustrated texts and has garnered him a veritable cult following.

Born and raised in Chicago, Gorey briefly attended The School of the Art Institute of Chicago before joining the US Army in 1943. He used his G.I. bill to attend Harvard University where he began writing and illustrating humorously creepy plays and poems. He’s perhaps best known for his Tim Burton-esque Broadway production of Dracula (1977) and art design of the opening credits for the PBS series Mystery!. In addition to writing and illustrating his own works, Gorey also created numerous covers and illustrations for books (T.S. Eliot and Samuel Beckett are just a couple of the authors to benefit from the illustrator’s collaboration), newspapers and magazines. This may seem like an unorthodox exhibition for LUMA given that their mission is to explore spirituality within art, but I’ll circle back around to this point later.

Naturally, I was expecting plenty of interplay between text and image within the exhibition given the nature of Gorey’s legacy as both a book illustrator and author. What surprised me, however, was the nature in which text was presented with the images. Lengthy wall chat panels often accompany illustrations (or series of illustrations), effectively subverting the traditional relationship between the two entities. While text-based images are usually employed to visually illustrate a narrative, in this instance the narrative is used to illustrate the images.

Wall labels are not the only method in which Gorey’s illustrations interact with text. In some instances, illustrated pages of a book are framed and matted along with a few words clipped from the story from which they’re drawn. Additionally, the illustrative text is sometimes printed directly on the page bearing the image. I know not whether Gorey had much say in where text was placed in relationship to his images on a given page; I have a sneaking suspicion the book publisher often made the final call on this matter. In the case of the framed clippings, the collector of the work most likely determined how much text should be included and where within the frame.

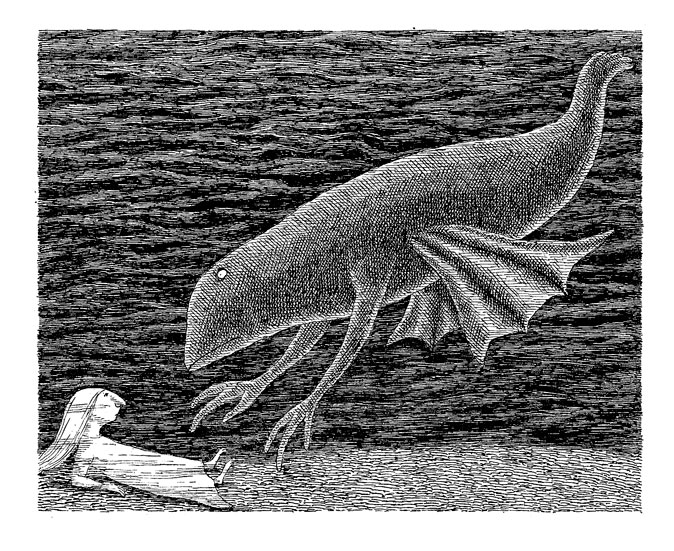

Yet the various ways in which the text is presented in conjunction with Gorey’s illustrations throughout the exhibition made it clear that the experience of both the artist’s images and stories is undeniably mediated by a third party. This ulterior party — whether publisher, collector or curator — has specific ideas on how essential Gorey’s words are to a specific image. The experience of his work is further mediated by the viewer who must decide whether to read the text or look at the image first. Of course, to disregard Gorey’s text would be entirely remiss. His words, always finely hewn and charmingly rhymed, required just as much crafting as his intricately penned illustrations. I’d wager that he would say neither was meant to stand entirely alone. The dynamic curiosity of his work rests on this interminable symbiotic tension between word and image, narrative and illustration.

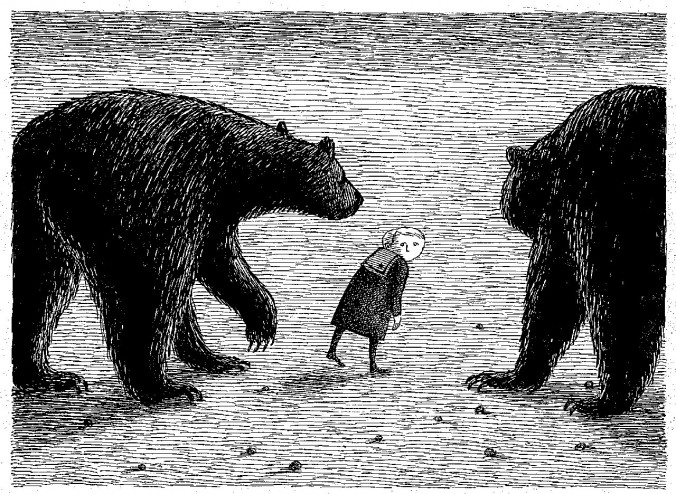

There is also a tension between the pleasurable and the frightening, the sweet and the bitter, the youthful and the adult in Gorey’s works, and he is well known for this. My favorite example of this is The Gashleycrumb Tinies; or, After the Outing (1963), a macabre alphabet book relating how each abecedarian character met his or her end through a perky alternating rhyme. For instance, “A is for Amy, who fell down the stairs; B is for Basil, assaulted by bears.” My personal fate of choice was, “N is for Neville, who died of ennui.” Poor Neville.

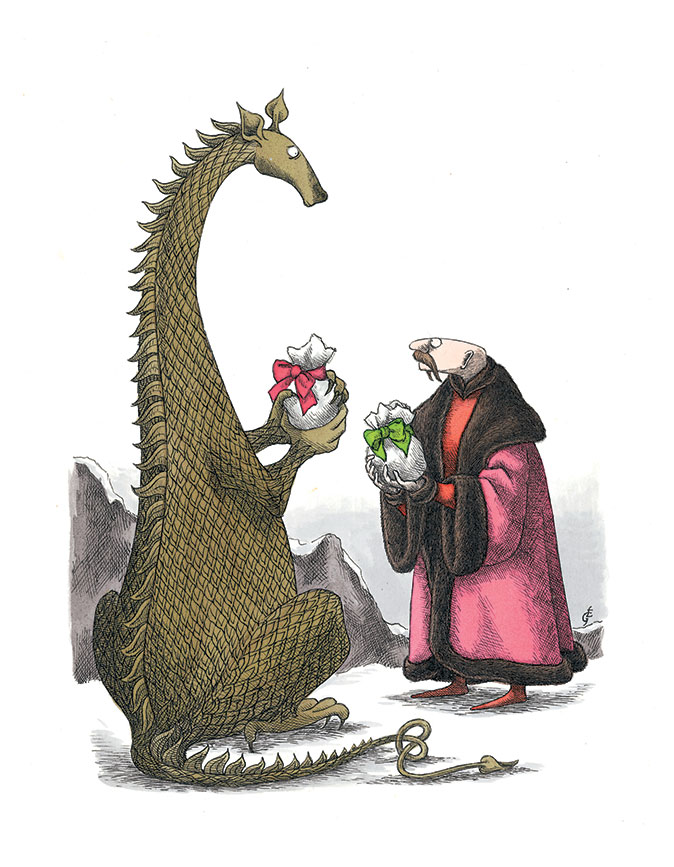

This kind of dark absurdity permeates all of Gorey’s work to some degree. Sometimes the illogical seems like just a flight of whimsical fancy, such as in Dragon and Man Exchange Gifts (1953), one of the few color drawings within the exhibition. However, more often than not, Gorey’s works provide a more sinister silliness, evidenced in series like Tragédies Topiaries (1992) in which unnamed persons are murdered by intricately trimmed shrubbery. Narrative is kept to a minimum within these works as only a single French word describes each garden fatality. For instance, “l’automobile,” written in a small scrolling script, accompanies the sketch of a car-shaped bush rolling over some poor soul.

There’s even a certain absurdity to Gorey’s technique. His illustrations, always meticulously drawn and tightly rendered, are densely articulated through repetitive dashes, dots, hashes and lines that intimate a kind of obsession. Indeed, the second half of the exhibition, G is for Gorey, C is for Chicago, includes a whole text panel explaining Gorey’s compulsive attention to detail in his wallpaper depictions; it cites the artist as lamenting one day that he had hoped to be more productive but had instead gotten lost drawing tiny bits of inconsequential wallpaper.

Gorey did not live in Chicago once he was discharged from the army, yet I believe that Chicago informs his work, perhaps not formally but thematically. While I do not know of any direct link between Gorey and, say, the Chicago painting giants Ivan Albright and Ed Paschke, the same themes of the absurd, grotesque, fantastic, surreal and darkly humorous all undergird their work. When asked why he represents violence and horror in such a blasé manner, Gorey was quoted as saying that he merely seeks to represent reality. The ability to render reality as inane, funny and unsettling all at once is perhaps not unique to artists of Chicago, but it does seem to be a special skill of many including Gorey, Albright and Paschke.

While viewing reality in this way may seem a bit depressing, I would argue that it’s fairly healthy; if one can’t discern the absurd in tragedy, one won’t be able to relish the sheer luck of happiness. Perhaps this skill is exactly what permeates Chicago ideology and culture. In this light, the whimsical, the absurd and the fantastic can be seen as a Windy City-specific kind of spiritualism, making the Gorey exhibition a perfect fit for Loyola’s museum. And while I’m not a native Chicagoan, after experiencing Gorey as deeply as LUMA’s rich exhibition allows, I’m willing to convert to his religion of the weird and wonderful.