Zapatistas: 20 Years of Pioneering a Grassroots Movement

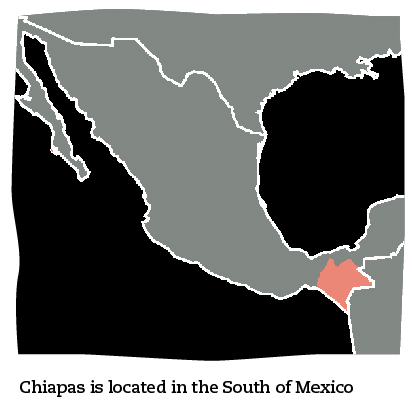

Twenty years after its first uprising, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), a revolutionary leftist group based in the state of Chiapas in Mexico, remains active and expertly organized. Composed mostly of indigenous people, the EZLN has challenged the assumption that indigenous groups and new media were incompatible and truly paved the way for contemporary political grassroots movements. As early as 1994, the EZLN used global communication tools — international press and later the Internet and social media — to organize, inform about, and represent their rebellion.

Originating in the ’80s, the EZLN, also known as the Zapatistas, first took action on January 1, 1994, the date of the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In preparation for the agreement to be signed, the Mexican government cancelled Article 27 of its constitution. The article, which protected native peoples’ communal lands from sale or privatization, had been what Emiliano Zapata first fought for in the revolution of 1910-1919. Rising against the infamous trade agreement, the EZLN sought to shed light on the harsh reality of the social and human conditions of the indigenous people in Mexico specifically in the state of Chiapas, where they make up 27 percent of the total population.

What started as a military action in January 1994 quickly shifted to an unarmed, non-violent revolt, which continues to develop away from the eyes of both the national and international media. Yet the Zapatista rebellion is still an example of a successful grassroots movement. Not only were they right about NAFTA and its disastrous impact on the lives of the poorest people in Mexico, they have developed autonomous forms of government in their territory, have pioneered the use of new media for indigenous movements and have empowered women by training them and giving them access to decision-making roles within Zapatista organizations.

Since the Spanish conquest almost 500 years ago, surviving indigenous groups in Mexico have been living in deplorable conditions. Although their rights as citizens are supposedly recognized in the second article of the Mexican constitution, racism toward indigenous people in Mexico is too present to be overlooked, and the majority of them (about 80% according to the National Human Rights Commission) live in extreme poverty.

Following its entry into a neoliberal system in the 1980s, Mexico has embraced a process of globalization in the hope of achieving the status of a “developed” country, yet failed to provide the entirety of its population with the means to adapt to such quickly changing environments. This abandonment of an entire part of Mexican society in the race for a first world seat, coupled with institutionalized indigenismo¹, were the trigger for the Zapatista revolt.

Every rebellion has leaders, and the Zapatista movement is no exception. Its charismatic figurehead is Subcomandante Marcos. Although his true identity remained mysterious for several years, the Mexican government asserts that behind the balaclava and the smoking pipe hides Rafael Sebastian Guillén Vicente. An award-winning student of philosophy from the National Autonomous University of Mexico who later taught at the Metropolitan Autonomous University, Marcos wrote more than 200 essays and stories and 21 books between 1992 and 2006. Paradoxically, his sister, Mercedes del Carmen Guillén Vicente, is the Sub-secretary for Migration, Population and Religious Affairs in the current government led by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, a party highly contested by the Zapatistas.

Marcos’ understanding of the politics of images, both in their creation and distribution, has guided the Zapatistas’ use of media. He coined the term “media terrorism,” which rural and social movement professor Peter Rosset describes as the way mainstream media “frightens people with unexplained images of threats and violence, making people support right-wing governments and repressive measures.” In doing so, media terrorism also tends to convey an inaccurate and uninformed image of grassroots movements.

From the beginning, the EZLN has used new media in impressively organized and ingenious ways. In an ironic and clever move, they started to use the communication media of globalization – the Internet, international press, and computer information technology – to fight the dominant cultural model of globalization and challenge the image that those same sources had circulated about indigenous people in Chiapas. The Zapatistas have a Facebook page, a Twitter account and a website, all updated on a daily basis. Through these media, they organize themselves, inform the rest of the world of their activities and most importantly, challenge erroneous conceptions about indigenous people. As Marcos described in A Zapatista Position Paper on Photography, indigenous groups are represented as “an anthropological curiosity or a colorful detail of a remote past” and are often considered to be incompatible with development and modernity. It is precisely this kind of assumption to which the Zapatistas are objecting through the creation and dissemination of digital content.

In addition to social media and the Internet, the Zapatistas have worked with the Chiapas Media Project (CMP), an award-winning organization that trains and supports indigenous people to create films, documentaries and video-based projects. Although CMP now only acts as a distributor for the EZLN, another organization called ProMedios has been created to keep Zapatista film production going. Both organizations have regularly updated websites and video databases. The films created through CMP are distributed in universities and cultural centers and at festivals throughout North and Latin America via Americas Media Initiative, a nonprofit with the mission to spread film made in the Americas by community media organizations. The goal is to educate other communities on the reality of contemporary indigenous groups and to circulate media based on non-Western aesthetics, challenging the cultural imperialism of the globalization era.

The Zapatistas’ success also resides in the self-governed territory they have managed since 2003. It represents a third of the land in the state of Chiapas, and its decision centers are divided between five villages, or as the Zapatistas call them, Caracoles (snails): La Realidad, la Garrucha, Morelia, Roberto Barrios and Oventic. The Caracoles function on the basis of a rotating self-government. They also have an autonomous healthcare and education system and are developing their own legal system. During the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Councils of Good Government), representatives of each Caracol gather to organize the resources they produce and the support they receive from the exterior and communicate among Caracoles and with the wider world through reports posted on their website. The members of the Juntas rotate on a regular basis and include both men and women.

Women play a very important role within the Zapatista community, a significant contrast with Mexican society, which, despite great improvements, remains in many areas a patriarchal and aggressively masculine society. As Rosset explained in a recent interview on Democracy Now, the Zapatistas believe that women ought to have “50% of all positions of authority in the self-government process.” In fact, they already form 50% of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee, which is the “maximum authority in the Zapatista Movement.” The most important female figure, Comandante Ramona, who died of cancer in 2006, opened the way for young indigenous females to hold decisive roles within the Zapatista movement. Comandante Hortensia, for instance, delivered the speech last January commemorating the 20th anniversary of the revolt in Caracol Oventic. Young girls living in the Caracoles attend the Zapatista autonomous schools, and as they graduate they take part in the Juntas, fully participating in the decision-making process of the Zapatista community.

President Peña Nieto has launched multiple reforms since his election to improve access to education, food and electricity, yet some crucial elements remain overlooked. The indigenous communities are unrepresented on the national political scene and the dialogue between the two entities has been at a standstill for the past 18 years. Many indigenous groups don’t speak Spanish, and the government’s representatives have no knowledge of native languages.

Although it is true that the Zapatistas haven’t revolutionized Mexican politics, it is undeniable that they have at least succeeded in tackling by themselves the issues that the government has failed to address. They have spearheaded online activism, paved the way for self-representation through alternative media and started a wave of awareness about indigenous issues.

As Mexico is vying for a seat at the First World table, it refuses to publicly acknowledge these thorny issues, to the point that it actually forgets to address them. However, the EZLN’s successful mediatizing of indigenous concerns means that the Mexican government won’t be able to turn a blind eye on it’s people’s uprisings for much longer.

¹ Indigenismo was an artistic movement which eulogized the indigenous roots of the Mexican identity. It was then appropriated

by the government who used images of glorified indigenous past, and traditional indigenous designs to promote Mexico abroad

and to secure commercial agreements.