Afghanistan remains in the midst of a deep humanitarian crisis, though many of us might not be fully aware. From political turmoil to human rights violations, the struggles of its people have far-reaching effects, including on global security and refugee movements. This article aims to raise awareness about the ongoing situation in Afghanistan and why it’s important for all of us to care.

In Block 16, Gulshan-e-Iqbal of Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi, the woman of the house, Shabana, who asked not to share her last name due to security concerns, buried herself deeper in the blankets as the doorbell went off at 7 a.m. It was Jan. 2, and mornings were chilly. She knew without looking at the front door camera that it was the garbage man, Karim, waiting for the day’s disposal, and that he would ring at least twice more before leaving.

She asked him if he could please come after 8 or 9 a.m. The man, in his late 40s or early 50s, already skittish because of the similar demands he’s heard from other houses, was hesitant as he explained why he couldn’t do it.

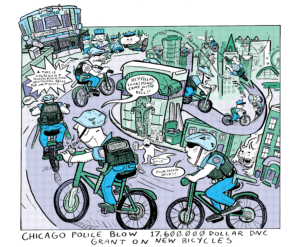

“The police do their rounds after 8 a.m.,” Karim said. “They round up everyone who looks like us and ask us for our ID cards. When they see we’re Afghani, they throw us in lock-up cells for being illegal immigrants.”

The group of garbage men come out around 3 a.m. after the police patrolmen finish their last round of surveillance. They spend the rest of the night sleeping on the sides of the road, and leave in the morning before the police come.

Block 16 is a low-level crime area. Police presence is not for intimidating criminals or for catching thieves and murderers as much as it is for the subjugation of those who carry the passport of Afghanistan, the country Pakistan helped destroy.

“I’m not an illegal immigrant,” Karim said. “My family has been in Pakistan for over 40 years. My kids were born here. They told us to come here, they let us live for decades; now they want to throw us out?”

“Not having your ID card is not an option. If you look Afghan enough, they throw you in either way,” he added.

Pakistan and Afghanistan have a history of mutual destruction. Since 2002, Pakistan has served as the epicenter of United States-sanctioned violence against Afghanistan. In the “War Against Terrorism,” Pakistan allowed the United States open access to its military bases and gained the status of being an anti-terrorist country, while also becoming the center to host terrorists when the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan during the cross-border disputes after 2001.

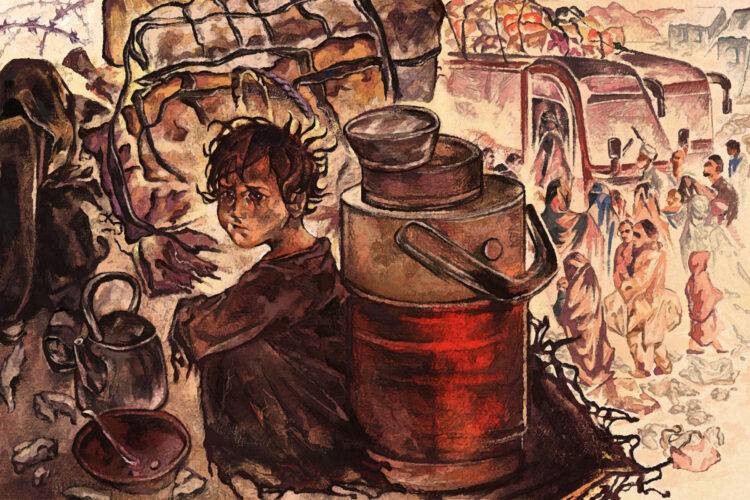

Before the United States’ invasion of Afghanistan, the country was already feeling the remnants of the Communist Taraki-Amin government, which had successfully driven out 400,000 Afghanis before 1980. The Soviet Invasion of 1979 led to the expulsion of even more civilians, making the Afghanistan Refugee Crisis the second biggest in the world after Syria. Over 2.6 million documented refugees, and more undocumented and asylum-seeking displaced Afghans have been driven out from their own country.

The Taliban officially came into power in Afghanistan again in 2021, which led the relationship between the two countries to worsen. Instances of border violence became more frequent and severe. A group from north-west Pakistan, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), has been credited with increased violence in the territory. The Afghanistan-Taliban has publicly rejected any association to it, but the Pakistan government still credits them for the upheaval in the region.

Both Pakistani and Afghan people have paid the price of this insurgence, in addition to the US-mediated warfare. Even far away from the Pak-Afghan border, the southmost city of Pakistan, Karachi, has witnessed decades of violence, credited to the Taliban and TTP.

*

In October 2023, Pakistan imposed a 28-day deadline for Afghan refugees to leave the country. Over 3.7 million people were expelled with the expectation of building their lives in Afghanistan, with over half of them never having lived in or visited the “home-country.”

According to Al Jazeera, Pakistan’s decision to deport refugees has been attributed to the lack of effort from the Taliban to control the cross-border violence. Despite decades of housing Afghan refugees, Pakistan has not signed on any international conventions and protocol regarding refugees. The Pakistan Citizenship Act states that citizenship is to be granted at birth unless the person’s father is an “enemy alien,” which Afghans are not considered — but even then, the right by birth doesn’t apply to Afghan refugees. Neither does naturalization.

Afghan refugees have been used as bargaining chips, and a ball in this game of politics, being passed around as seen fit by these two governments.

People in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa— the northernmost province of Pakistan that shares borders with Afghanistan— have long held ethnic and cultural ties to Afghans, being from the same geographic region, and thus have similar facial features. As a result of inherent racism against Afghans in Pakistan, even Pakistani Pashtuns have been deported despite being Pakistan nationals, simply because they looked Afghani.

*

Elders in my family take every chance they get to talk about whatever the ongoing PTI (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, a political party) scandal is, the refugee crisis, the Balochi genocide (Pakistan’s government has been systematically killing residents of its province, Balochistan), the sadisism of Modhi, the prime minster of Pakistan’s next door neighbor, India. It’s a given that after every family dinner, when the chai is being served, someone will bring up the latest WhatsApp trend and start a convoluted, half-factual, hahalf-backed-up-by-forwarded-messages debate.

On December 12, two days after I landed in Karachi during my winter break, I was able to see first-hand how a typical middle-class family was reacting to this atrocity being committed by their government.

“It’s this corrupt government, they came in as temporary office-holders, now they refuse to leave and continue making a mess of this country,” said Hamida, my grand-father’s sister. She’s on the edge of 80 years, and still hyper-aware of everything that passes through her WhatsApp texts.

Her brother-in-law Isaa backed her up, and echoed what three others had already said.

“Who’s going to do all the menial tasks, the industry work, the street manual labor, now that the country has expelled them? Did anyone think of that? Did the so-called government think about the crisis they’ve imposed on us?” said Isaa.

There was a clinical detachment in his breakdown of the Afghan refugee crisis.

On the dining table, in a house filled with people who had once been forced out of a border at great cost to themselves and their families, the conversation about 3.7 million Afghans was through the lens of Afghans as garbage-workers and street-cleaners.

Hearing the elders talk confirms that they’ve never tried to hear Afghans, see them, or think of them as people. Al Jazeera’s November article contained a quote from an Afghan-Pakistani woman who said “Kill me here, or let me live, but I am not going to go back.”

It takes a certain amount of dehumanization, both as an individual, and also as part of the collective narrative propagated by the media and the government, to leave a person emotionally unmoved after learning of someone else’s displacement.

The worth they assign to refugees is apparent in their dissociative conversations about them, but also in the way Shabana never found out the last name of her Afghan garbage man, or why Saba, her neighbor, only lamented her maid’s deportation because of her loss as a house-helper.