The cinema is a trick. The projectionist runs reels of film, at just a fast enough rate to trick us into connecting disparate images together, creating the illusion of motion in our minds. What were two static images becomes one continuous movement. What was once static, inert, now exposed to light, becomes dynamic. We build the bridge between the pictures, filling in the blanks left behind. The question is whether Sam Mendes, writer-director of “Empire of Light,” can successfully trick us into ignoring the gaps.

“Empire of Light” is Mendes’ tribute to the power of cinema and cinemas, much like Spielberg’s “The Fabelmans” from only slightly earlier this year. Unlike the country-crossing and time-jumping saga of “The Fabelmans,” “Empire of Light” is located entirely within the coastal town of Margate in the 1980s.

Olivia Colman plays the film’s lead, Hilary, an assistant manager at the Empire, a local cinema. She’s later joined by Stephen, played by Michael Ward, a new hire, and one of the few black men in this town that is polluted by skinheads and more casual racists. Rounding out the rest of the Empire’s staff is Colin Firth as Donald Ellis, the Empire’s vindictive and glory-seeking manager; Tobey Jones as Norman, the reticent projectionist; and several other cashiers, cleaners, and ushers.

The film oscillates between larger societal ideas about prejudice and abuses of power, and more personal themes about the power of cinema. The ideas aren’t actually connected through the film’s plot, but it doesn’t feel like Mendes cares if they are either. Those ideas pop up in bursts but are largely relegated to the sidelines when put beside the relationship between Stephen and Hilary. Their friendship is the focal point of the film, defying conventional labels, as the two close the gap despite the many differences between them.

Olivia Colman as per usual is a powerhouse as Hilary, who loves her job but refuses to sneak a peek at the films. Colman has proven herself to be absolutely singular in her ability to layer the complexity of characters simply behind her eyes. She’s smiling, but her eyes betray an emptiness, a searching, a yearning, which she cannot seem to fill. Michael Ward as Stephen is also searching, though for him it is the vastness of the future rather than the emptiness of the present that he has to contend with. Ward is terrific as Stephen, who he brings a lightness and humor to, despite the character’s constant awareness of his otherness.

Both actors are marvelous in their roles, making their relationship feel believable and complex. But it often feels like the script demands too much of them as individuals, to carry their arcs. Hillary’s issues with her mental health in particular feel like scenes more driven towards winning an Oscar, rather than to affect the plot or deepen the film’s themes.

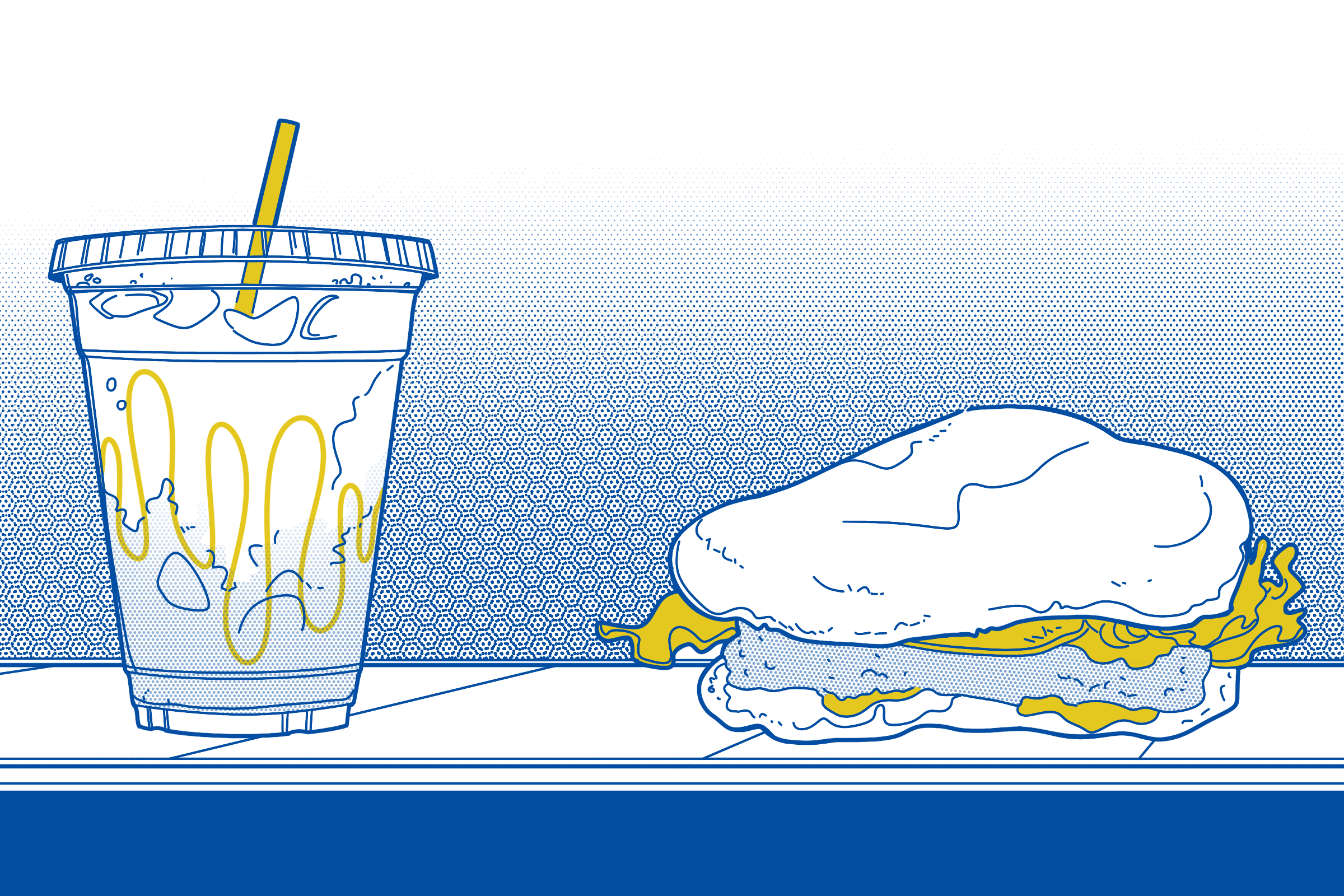

And there are many themes: human connection, racism, violence, sex, Thatcherism, Blackness, and probably the most engaging of the bunch within the movie, is film itself. It’s fitting that a movie about movies looks as good as this one with Roger Deakins’ crisp cinematography, catching the traces of light in every frame, whether it is a fading cigarette or a beam of light through a dusty curtain. We’re constantly reminded that all of this is only possible because of the light.

These majestic visuals are backed up by the cutting soundtrack from Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor. Their music adds a peculiar eeriness to the small town and a melancholy that pervades Hillary and Stephen’s lives. I found myself eager to revisit many tracks, mesmerized by the mood they invoked.

The problem is that its technically marvelous cinematography, its stellar performances, and its evocative soundtrack do not serve the film’s core. Because outside of its two central characters, that core is left largely missing. And the only reason we feel something is missing is because the film has such a scattershot approach to its many themes. Mendes’ screenplay has us moving from moment to moment without much clear focus, jumping from topic to topic with surprising bursts of violence and mania. It would all be fine if the film’s scope was narrower and concerned with the reel spinning in the projectionist’s booth, which seems to me as Mendes’ primary interest. The remaining themes in the film’s wide array of interests prevent us from approaching any of them in deeper ways.

I personally was very gripped by the film’s fascination with film, especially with the character of Norman (Tobey Jones), the projectionist who treats his booth like a shrine, adorned with posters of movie stars from yesteryears, juxtaposed with Hilary’s own stubbornness to ever watch a film herself. This culminates in a moment that is a worthy tribute to the physical space and tangible value of the cinema. Yet when the movie kept going after that point, it almost felt like Mendes was trying to prove he had other thoughts on his mind too, like we were walking out on a date with him after he detailed the contents of his Criterion collection.

By the film’s end, I was moved by its story and its characters. But after ruminating on it for some time, I realized how much of the film was filled up by my own love for the cinema. To me, the cinema is a special place that exists outside of time, one deserving of reverence and awe. So I understand Mendes’ impulse to write an entire film about a cinema, to unpack its power and ability to connect people. What I don’t understand is Mendes’ decision to attempt to tackle racism, mental health, and sexual abuse all within this same film, without adequately giving time to any of them. If anything, trying to cover so much ground undercuts the film’s central relationship, obscuring the people with the constructs that oppress them. It’s as if the reels are spinning but frames are missing from the strip. I managed to fill those spaces with my own love for the cinema. But without that, “Empire of Light” is more its flickering dark frames than it is beams of light.

Myle Yan Tay (MFAW 2023) cares a lot about movies and comic books. One day, maybe they will care about him. Find more of his writing at www.myleyantay.com.