People Matter headquarters is located on the ground floor of a three-story brick building beneath I-90. Walking to it from the Cermack-Chinatown redline stop, you pass by Chinatown Plaza (“new Chinatown”), continue down Wentworth Avenue (“old Chinatown”), cross the Stevenson Expressway, and arrive in a mixed commercial-residential area.

The first time I visit is on a spring Saturday and the rain has not let up for three days. Despite the conditions, both new and old Chinatown are crowded with people, and the smell of hot grease and sweet bean and root pastes overpowers the scent of wet pavement. I walk through all that and keep walking until I end up on the border of Bridgeport, in an area of Chinatown that lacks a bustle the neighborhood is known for.

When most think of Chicago’s Chinatown, they think of the Plaza and Wentworth, they think of hot pots and boba shops and red lanterns strung between rooftops. “In all actuality, people live here, people work here, people have families here,” Consuela Hendricks, co-founder and creative director of People Matter, tells me. “We felt like that’s something to bring attention to.”

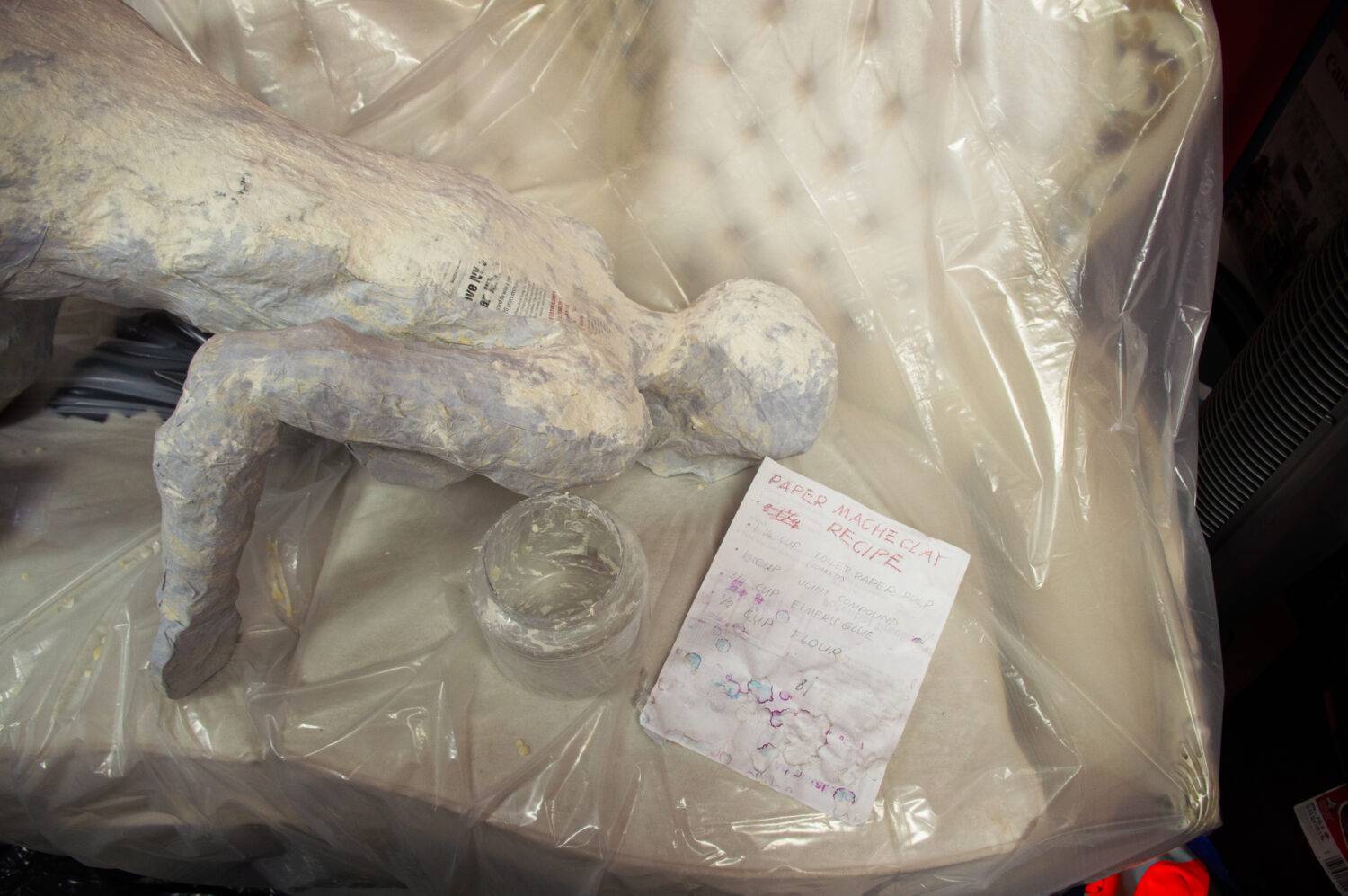

After I lay my dripping raincoat and backpack in their front greeting room, Angela Lin, the other co-founder of People Matter, leads me into a workspace where Hendricks is clacking away on a laptop. Eian Hsu and two young volunteers, Diana and Erica, are cutting through PVC piping. It’s the first day of work on a public sculpture that they’ll plant beneath the painted overpass at Ping Tom Memorial Park. The vision is to create a dinner scene: A Chinatown family — grandfather, mother, and child — seated around a table. “It should be more realistic than the ‘super complete, super perfect’ nuclear family,” Lin says. “A lot of kids in Chinatown have parents that travel to work for like three, four months at a time in like New York’s Chinatown.” But that, she says, is all subtext.

The location, like the sculpture, also has strategic undertones. Ping Tom Park is a hub, complete with a playground, a pagoda, ample grassy lawns and one of the best views of Downtown’s skyline from the South Side. It’s a place where residents from nearby Pilsen, Bronzeville, Bridgeport, and South Loop mix with Chinatown residents. And building bridges between Chicago’s ethnically-enclaved neighborhoods is central to the purpose of People Matter.

“The race relations portion, I would say that that’s a pretty distinct part of what we do,” Lin says. “We always do things through an intersectional lens. Chicago is a pretty segregated city, and a lot of these low income communities of color share the same schools, hospitals, and institutions, but don’t necessarily talk to each other. They may have cultural barriers or language barriers or, you know, racial tension. So we do a lot of work that addresses each group by itself, and its own specific needs, but also everyone’s collective needs.”

Lin and Hendricks met in 2017 during a volunteer project (coincidentally, also in Ping Tom Memorial Park). Hendricks, who was born in nearby Englewood, had been working in Chinatown since she was 16. Lin had recently moved to Chicago from Atlanta and was working as a community organizer with the Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community (CBCAC) to create the murals at Ping Tom. “The first few days of work was very tense,” Lin recalls. At the time there was an ongoing, ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to close a nearby, mostly-Black elementary school, and turn it into a Chinatown high school. “There was a lot of racial tension,” Lin says. “I just remember being like, ‘oh my god, what is happening?’”

Lin and Hendricks became close friends, and continued volunteering and working together. They were aspirational but grounded. The non-profits they worked with focused on meeting basic needs, but fell short of empowering communities. A couple of years after meeting, they decided to form their own non-profit.

People Matter does focus on meeting basic needs in the Chinatown community. They hosted COVID-19 testing sites and worked on spreading awareness about the Census. But their work is pulled along by an undercurrent of improving race relations in their community, an issue that many organizations tip-toe around. Their first gathering, held in January 2020, was an event at the local library called “Highlighting Black Heroes in Chinatown.” They followed up with language classes to close communication gaps and started the Tackling Anti-Blackness in the Chinatown Community (TACC) subcommittee to continue hosting events and workshops.

In the past two years, they expanded their leadership team and their neighborhood reach, hired staff members, and connected with over 3,000 members of the community to gather feedback. “We’re talking, door knocking, calling, asking people what they want to see in their community,” Hendricks says. Some of the group’s other initiatives include a Housing Committee to combat gentrification, and a pop-up community garden with local middle and high school students.

“People say, like, ‘wow, you work in a lot of different things,’” Lin says. “That’s because that’s what community members say that they want. Our work is very much based on feedback — well, taking the feedback and putting it through an ethical lens.”

The family sculpture was inspired by an exhibit opening at the Chinese American Museum of Chicago, which People Matter works closely with. “Era of Opulence: Chinese Fine Dining,” a mini-exhibition, opened in late-April. A larger exhibition, “Chinese Cuisine in America: Stories, Struggles and Successes,” is scheduled to open in the Fall.

At one point Lin tells me that they expect it to get vandalized and damaged, that’s just what happens to a lot of public art. Despite the risk, they want it in a public space for community members to interact with passively. The point isn’t to confront park-goers, it’s to subtly, almost subconsciously, familiarize residents with one another. It’s another way of building the bridge, and then beautifying what’s beneath it.

Parker Yamasaki (MANAJ 2023) is the managing editor at F Newsmagazine. She is looking for a sunnier place to sit.

Natalie Olivia Plata is a staff photographer at F News.