The last time I ever ate meat I was very inebriated sitting in the backseat of my friend’s car on our way home from a Britney Spears concert. Rolling through a McDonald’s drive thru off the highway, I ordered my last supper of 10 chicken McNuggets, french fries, and a large chocolate milkshake.

Fast forward to today, and I’ve been a vegetarian for over a decade. The catalyst of my vegetarian transformation was a project for AP Environmental Studies, where we researched a lifestyle change that would positively impact the environment. For my research, I read books about the inhumanity and brokenness of our food system, including unsustainable land use practices. Claudia Tam for Earth.org writes that global farmland use could be reduced by 75% if everyone in the world adopted a vegan diet. According to Ann Lowrey for the Atlantic, “Food production counts for roughly a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), and limiting global warming will be impossible without significant changes to how the world eats.”

The people who are most likely to pay the price of climate change are typically the most marginalized and have contributed the least GHG. Tam points out in her article that millions of Indigenous People have been displaced because of Amazon deforestation “to clear land for grazing animals and their feed.” Similarly. Rachel Massey of the Global Development and Environment Issue discusses similar trends in her report on Environmental Justice: “Low-income communities and minority ethnic groups often bear the most severe consequences of environmental degradation and pollution.”

After learning the beefy truth, I gave up red meat and then graduated to poultry and fish. Within two years, I had quit meat cold turkey. (Pun intended.) However, I still ate animal products such as dairy, butter, and eggs. I couldn’t imagine brunch without an omelet and I had an illicit relationship with late-night cheese pizza. If goat cheese was involved, I wanted in.

My full transition to veganism took me about 10 years. I usually refer to my current dietary ideology as “Vegan With Benefits:” I eat vegan most of the time, but if I need to eat animal products for convenience or because I’m really craving something, I allow myself to be flexible. I’m a vegan in the sheets, vegetarian in the streets, if you will. Naming this flexibility is important, because the word “vegan” can be intimidating. When people find out that I don’t consume animal products, they treat me like I’m trying to indoctrinate them into a joyless, butter-free cult, or they are afraid they might turn into a head of lettuce if we make eye contact.

A lot of the “fear” and hesitation surrounding veganism is largely due to militant veganism. Organizations like PETA use animosity and controversiality to preach an all-or-nothing approach to a greener diet. This version of vegan activism seeks to shame, guilt, and villainize anyone who still consumes animal products under any circumstances. PETA has used a cornucopia of questionable practices to spread their message, including making claims that dairy products cause autism, producing fatphobic marketing campaigns, and comparing animal cruelty to the Holocaust. Arguably one of the more offensive PETA moments occurred in 2015 when they tweeted, “The best #Thanksgiving meals are the ones no one had to die for [wink emoji] #Thanksliving.”

PETA’s blatant disregard for the oppression of Indigenous People in the U.S. is a perfect example of the big pieces that are missing from our conversations about veganism, land use, environmentalism, or all of the above. As Raphael Miller outlines in their essay, “It’s Time We Decolonized White Veganism,” the loudest voices in the vegan community are often those that dominate conventional discourse: White, cis-gender, able-bodied, thin, and affluent. When most people picture a vegan, they likely imagine a waifish blonde woman carrying a yoga mat around Whole Foods and side-eyeing the hotdogs in your basket. She self-righteously declares that consuming animals is cruel and inhumane while she drinks green juice.

This trope is a hyperbole, but also sometimes scarily accurate portrayal of, white veganism: The centering of white supremacy in conversations about veganism. Focusing on this narrative erases BIPOC identities and histories within the vegan community; it neglects to acknowledge environmental justice; it denies the realities of who has unlimited access to food and who doesn’t; and it is culturally appropriative and insensitive. If the vegan community wants to encourage everyone to adopt a more meat-free lifestyle, we first need to address the way that food is distributed in our society. Adopting a completely vegan lifestyle is not possible for people who live in food deserts or can’t afford to purchase fresh produce or vegan ingredients.

For the record, eating meat has not caused the problems persistent in our world food system or the climate crisis. The Lakota People’s Law Project points out that Indigenous Nations hunted animals for centuries without harming the environment, focusing on only taking what was needed to sustain themselves and their communities. Jonathan Safron Foer acknowledges this in his book “Eating Animals,” citing that many cultural traditions include consuming meat and the idea that we must collectively banish these practices is obtuse. The practice we must banish is factory farming and its progenitors: corporate greed and capitalism. Instead of alienation, vegans should invite people in with the core values we claim to preach: kindness, compassion, and conservation.

I’ve had many friends share their personal flirtation with veganism, but also confess they “couldn’t give up steak, or cheese, or fill-in-the-blank.” The thing is, I think you don’t have to give up animal products entirely to make environmentally conscious choices. Whether your favorite food is BBQ short ribs or you also prefer “rabbit food” like me, it is possible to alter your eating habits if you want to without succumbing to all-or-nothing thinking. Campaigns like Meatless Monday are a much more accessible, attainable, and inclusive message regarding plant-based eating: In my opinion, the world eating less meat produced or farmed in an ethical way is a step in the right direction.

So go ahead and call yourself “Vegan with Benefits” if you want. I promise I won’t accuse you of plagiarism: You can have your vegan food and eat butter too.

***

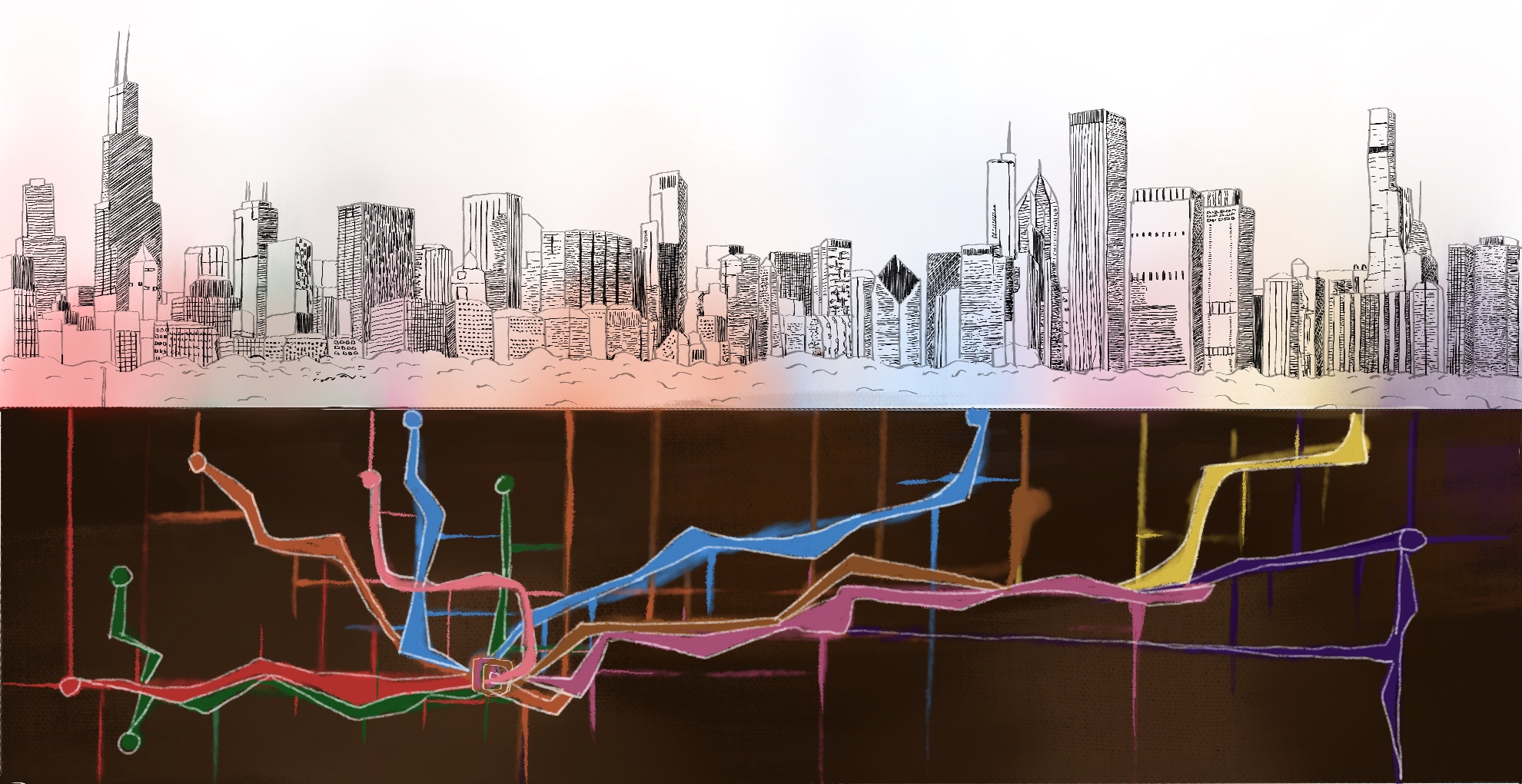

If you’re interested in eating more plant-based food around the city of Chicago, I’ve provided a list below that will hopefully inspire you to eat a little more sustainably in the future.

Loving Vegan Café | Uptown: This cute little café has the best buddha bowls you’ll ever eat in your life.

Bloom | Wicker Park: New and getting lots of hype recently.

Kitchen 17 | Logan Square: Famous for their vegan deep dish pizza but I personally think their “wings” and desserts take the cake.

Chicago Diner | Boystown, Logan Square: Get the spicy “chik’n” sandwich. Thank me later.

Blue Sushi | Lincoln Park: Sushi is the pre-vegan food I miss the most, so I nearly cried when I tried their vegan “spicy tuna roll.”

Penelope’s Vegan Taqueria | River North: Proof that manifestation is real because I have been begging the universe to send a great vegan restaurant to my neighborhood.

Handlebar | Wicker Park: BRUNCH! BRUNCH! BRUNCH, BRUNCH, BRUNCH, BRUNCH,

BRUNCH! EVERYBODY! (To the tune of Lil Jon’s “Shots,” please and thank you.)

ALTHEA | Streeterville: If you’ve binged “Bad Vegan” you’ll recognize the same Mathew Kenney. Fancy with a capital F. Delicious with a capital D.

Soul Veg City | Grand Crossing: Southern soul food with a juice bar and local art exhibits.

B’Gabs Vegan Scratch Kitchen | Hyde Park: Creative vegan options, juices, and smoothies.

Jamisen Paustian (MAATC 2024) colors more than most adults, but she rarely stays inside the lines. @jamis3n