“Moving Pictures” is a column by Myle Yan Tay (MFAW 2023) about the movies we love, the tropes we can’t stand, the underrated gems, the overrated schlock, and inevitably, why “Paddington 2” is cinema in its purest form.

“What do we leave behind when we go?”

It’s a question that many artists ask themselves. Sometimes it’s asked when the paint meets the canvas, when the fingers hit the keys, when the record button is hit, when the cel is finished, when the director says cut. Sometimes it’s asked at the very back of the brain, subdued in the hidden recesses of our consciousness while we wait to fall asleep.

It’s not a question limited to the artist. Everyone asks themselves the question at some point. Some people leave behind children. Others leave behind vaults of gold, cash, BitCoin; whatever their devil may be. But at some point, all of us have to contend with our mortality.

I have to admit, my beginnings in writing stemmed from a desperate desire to become immortal. I very much wanted some words to remain on this earth, as part of me, even after I go. Part of me still clings to that idea — that my work is only valuable if it preserves some part of me that transcends time.

“The French Dispatch” is innately concerned with temporality. Baked into each of its five or so plots is the transitory nature of experience; that some things will certainly end. But it is never dour or nihilistic. Despite the fact that we are watching a finished product of a film, the film itself is invariably about the process of getting to the final draft. And what is more temporary than the journey? The work must be completed, and we arrive at the destination. But the path taken to get there is invaluable.

I’m working very hard to avoid saying, “It’s not about the destination, it is about the journey”. Once I say it, I’m undercutting the work “The French Dispatch” does to communicate the cliché without ever going near it. Its central frame, of a magazine putting together its final issue, is as close as we get to the film explicitly stating this adage. The full name of that magazine is The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, run by expats living in the fictional French city, Ennui-sur-Blasé. In Ennui, these expats, be they photographers, illustrators, writers who write, or writers who don’t, are putting together the magazine’s farewell. But the process isn’t glorified as an abstract. It’s celebrated with the people involved.

Benicio Del Toro is Moses Rosenthaler, an imprisoned homicidal artist who cannot create without the love of his muse. Frances McDormand is Lucinda Krementz, a journalist who cannot help but get involved in the story she is writing about. Timothée Chalamet is Zeffirelli, a young revolutionary, writing (and feverishly revising) his first manifesto. Jeffrey Wright’s Roebuck Wright recites one of his articles to a live studio audience, providing little interjections about how he ended up writing for the French Dispatch. And in between each segment, Bill Murray, as Arthur Howitzer Jr (the French Dispatch’s editor and founder), gives the writers notes, reads their first drafts, and polishes their final versions. The process is there, right in front of us.

But it’s behind the camera too.

I have always revelled in Anderson’s stylized cinematography, his use of vibrant colour, and the unnatural pace of his dialogue in his other films. But it always felt appended on, like zest used to lift the film’s plot higher. In “The French Dispatch,” his style is critical to the film’s themes — you cannot help but imagine the process that goes on to make “The French Dispatch” look the way it does. Techniques like the Russian nesting doll of stories, the backdrops rotating behind a stationary cyclist, and sets always in transition serve to constantly remind us that we are watching a movie. More than that, we are watching people put together a movie. It’s not just coming from one man. It takes a whole village.

It takes actors moving from strict blocking points, just so the profile of their nose appears on screen. It takes musicians, scoring a credits sequence with hundreds of names flying by. It takes animators, crafting an eccentric wild car chase sequence, which really, at its heart, is about a boy and his father.

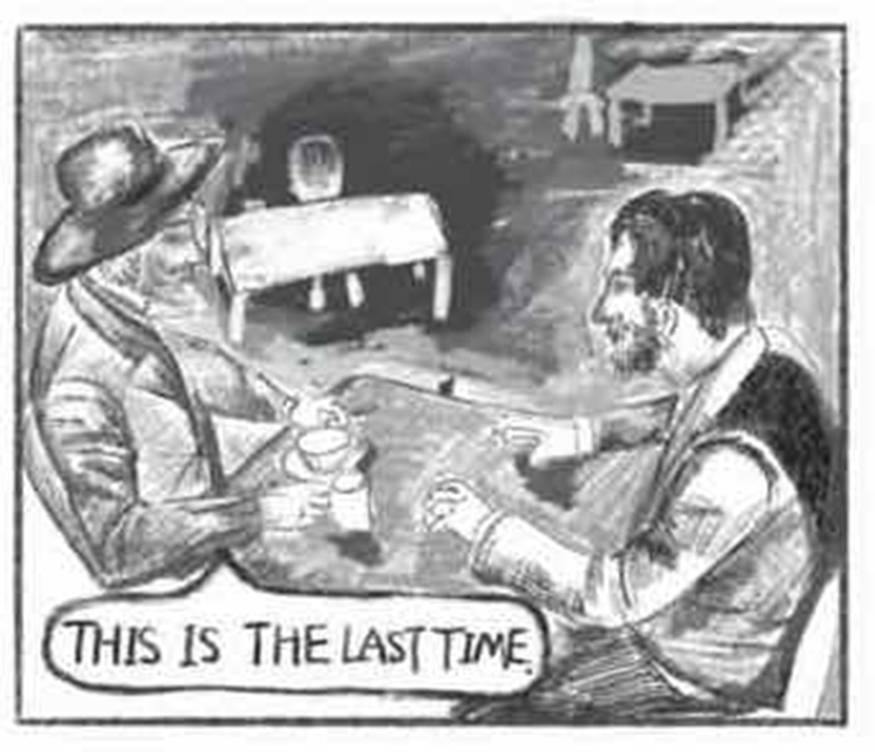

Speaking of that incredible animated sequence, “The French Dispatch,” though ostensibly about a magazine publication, is a tribute to art in its many forms. Again, it comes up in the literal focus of the film, with the Dispatch’s journalists, Benicio Del Toro’s portraiture, or Stephen Park’s Nescaffier, the culinary genius. But it’s also embedded into the film’s form. There’s the framed narrative of the magazine. There’s the animated car chase, delivered as a comic strip. There’s the narration from the journalists, bringing us from scene to scene within their own articles. There’s an impeccable fictional West-End production, showing us a playwright’s interpretation of one character’s decision to abscond from the military.

Some may find these formal choices confusing, and the overall film’s narrative inaccessible. But regardless, the film’s boldness cannot be denied. There is clear deliberation in the film’s choices, which even when I disagreed, I couldn’t help but respect the audacity to choose it.

Art, and the process of making art, is in every element of this film. And these characters end up in this process almost by necessity. They are plagued by a haunting loneliness, a solitude that follows them. Because as the film constantly reminds us, making art feels like a lonely process … except it isn’t.

When the film comes to a close, each of the journalists, each either chasing or running from seclusion, find themselves surrounded by their peers. Their final act is one of collaboration, to commemorate the French Dispatch and the man who made it happen. Each of them — the journalists, the accountant, the illustrator, the writer who never writes, the waiter who serves their food — come together to be part of one final article.

In the end, we don’t find out what they write. We are not treated to the fruits of their collaboration. We do not get to find out how the man and the magazine are memorialized. But it doesn’t matter. Because neither the man, the magazine, nor the very article they are writing live forever. It is, however, being written. The legacy we leave behind as artists may take the form of our work, but it is in the writing, the making of that work, that the best things are found.