In “Loving the Monster,” Sidne K. Gard explores the definitions, creation, and fascination with monsters in pop culture.

If you were offered a drug that traded you unlimited creativity for your humanity, would you take it? Would you quite literally kill for your art? This is the question at the heart of “Red Tide,” season 10 of “American Horror Story.” Rather than witches or ghosts or other supernatural beings portrayed in seasons past, this time the monster the narrative puts in our midst is one more mundane, yet more nuanced. Simply put, the monster and the writer are one and the same.

“American Horror Story” has officially entered its tenth season. The show is widely recognized for its anthology format and well-known cast — Sarah Paulson, Lily Rabe, and Evan Peters, to name a few. Though the seasons are loosely set in the same world, each offers its own unique premise and title. Season 10 is billed as a “Double Feature,” telling a different story in the first and secondhalves of the season. The first half of this double feature is “Red Tide,” a psychological, horror-based look at writing and the artistic process. The first episode introduces us to Harry Gardner, a failed television screenwriter played by Finn Wittrock, his young daughter (Ryan Kiera Armstrong), and his pregnant wife (Lily Rabe), arriving at a winter vacation home in tiny, eerie Provincetown, Massachusetts. In true “American Horror Story” fashion, things go quickly awry for the family, and it’s not long before the bodies start dropping.

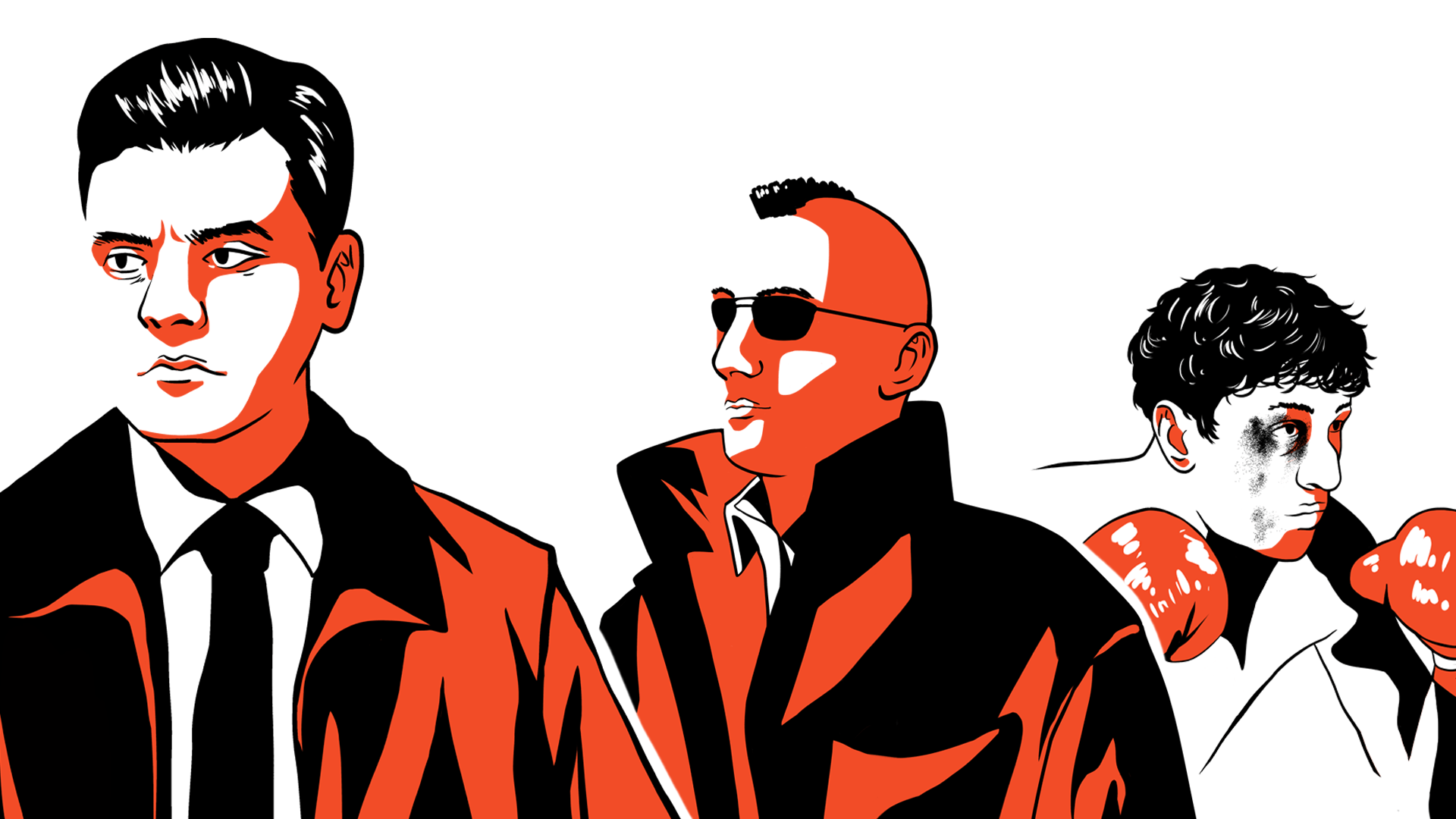

Harry is given a black pill by Austin (Evan Peters), a famous playwright and actor. Once Harry takes the pill, he becomes incredibly prolific and his writing becomes truly beautiful, but he is simultaneously overcome with apathy for anything that isn’t his artistic endeavours. Even more worrisome is the intense bloodlust the black pill brings. Although allowing him to push his writing to heights never before achieved, the pills are turning him into a vampiric artist as he now needs to drink human blood for the sake of artistic creation.

When Harry confronts Austin about the pills, we learn something rather interesting about their effects — the pills only work for those who have true talent. Anyone who is a “hack” and takes the pills is overcome with rage and envy. They become pale, bald creatures stuck somewhere between a vampire and a zombie, doomed to a life on the edges, stalking the town and attacking unsuspecting victims. This is the central premise that haunts the season and virtually all of the characters in it — is it worth taking these pills and thus risking your life on whether you have true talent, and is it worth killing for your art to be truly great? In the world of “Red Tide,” talent is a binary. Either you have it or don’t. The questions the characters face boils down to if they believe they have true talent and not what makes true talent. The show is more interested in the desire and repercussions of talent than exploring what makes someone talented. Over the six episodes of “Red Tide,” we see the Gardner family struggle with the bargain the pills present, and ultimately it destroys all three of them.

Every character we see takes one of these black pills, and ends up a monster — one of the “pale people” or a vampire artist willing to kill their newborns, their competition, and the people they love. There are no ghosts or supernatural creatures this season. The only monsters are the artists, both those with talent and those who ache for it. In “Red Tide,” in order to truly reach artistic fame and potential, all one has to do is decide if the price of admission is worth it, and that price of admission is becoming a monster.

Both pop culture and I share a fascination with monsters. Modern media is filled with monsters, from horror movie slashers to teen heartthrob werewolves to grouchy trash-can dwelling puppets. Truthfully, I find myself connected more to the monster in a story than the humans they love, terrorize, or coexist with. But a monster must have meaning. For example, Frankenstein is a discussion on the nature of creation. There are many ways to read into the narrative and to interpret the monster.

In analyzing monsters, we can come understand the monster and in some cases seek to love the monster. The monsters of “Red Tide” are incredibly human. They are artists, writers, musicians, and actors. They want to be adored, to be held up as amazing and influential. They will kill whoever they have to, drink as much blood as they need to, and risk their mental capacity for the chance to be a so-called true artist. These creatures, to me at least, feel both much easier to relate to than many of the ghosts and witches in “American Horror Story,” and yet much more unsettling. Whether talented or not, the characters of “Red Tide” are all ultimately consumed by their own art.

The final voice over of “Red Tide,” shown over a sequence of zombie-apocalypse-esque mayhem, ends with a message to the audience. “Those who achieve greatness only do so because they are fucked up enough to push through the pain and failure to reach your potential. At least with these pills, the world can find out if you’re any good. To be told we are talented — isn’t that all we ever want?” As a young artist and writer, I can’t deny that there have been times when I’ve been willing to give anything to ensure my words will be remembered. I think most of us at SAIC feel the same. Is it so crazy to think some of us would become monsters for their art?

As artists, we all have inner monsters; inner demons. We could easily succumb to our art, but we should not fear the artistic monster. We must learn to accept our monsters and in doing so, come to love them.