In her last book of essays “The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays,” published in Aug. 2020, poet and essayist Elisa Gabbert surprises readers with her honest analysis on compassion, disaster, disease, trauma and vanity — all relevant topics in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though these essays were written between 2016 to 2019, this book uncannily seems like a cautionary tale to the events that unfolded last year. The extensive research accompanied by the vulnerable anecdotal aspect gives each piece a cutting tone that exposes the collective mind’s private thoughts of despair and annoyance with our reality.

Gabbert’s third book of essays is an easy read about difficult subjects. She tackles the topics in what The Washington Post’s review describes as a “drone’s-eye perspective.” Her panoramic view on catastrophes is rooted in the shape of “hyperobjects”— a concept she references in her essay “Big and Slow” from philosopher Timothy Morton. Hyperobjects are “something that is ‘massively distributed in time and space relative to humans.’” An ongoing event that is happening everywhere, all the time, being so great we are unable to comprehend it or visualize it.

This reminds me of David Foster Wallace’s line in his famous 2005 commencement speech, “There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’”

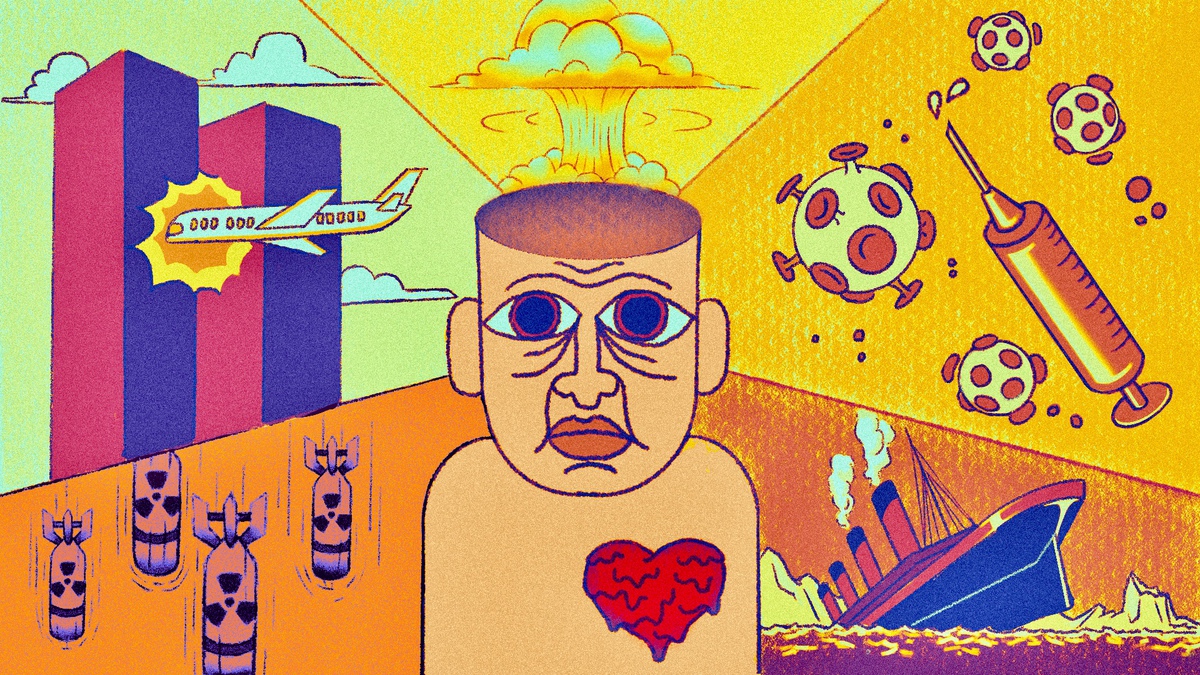

From historical landmark events like the sinking of Titanic, the nuclear attack to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the nuclear accident of Chernobyl, 9/11 and the Holocaust to chronic pain, hysteria and PTSD, these essays are meant to reveal the flaws of our narcissistic aspirations as society and how our fascination with tragedy ultimately prevent us from actually caring. Gabbert refers to disaster as a spectacle in which we are accomplices: “the way we glamorize it and make it consumable; the way news turns disasters into ready-made cinema.” She lets us know, in a deterministic tone, that we only focus our attention to world issues so we can feel like good citizens, while knowing we can’t actually solve them.

However, Elisa Gabbert isn’t trying to appear morally or intellectually superior. She isn’t trying to blame anyone or make the reader feel like a monster. The personal anecdotes that talk about her role as wife and caretaker when dealing with her husband’s chronic illness gives foot to her exploration of “compassion fatigue,” which she describes as “a sense that proximity to trauma could itself be damaging, like secondhand smoke.” This trauma is translated to media studies as the overexposure of horrific images, causing the viewer to “shut down emotionally, rejecting information instead of responding to it.” Although, even after sharing this, she points out some people might be exploiting this to justify pure indifference.

I see this book as a wake-up call which we received too late. We are now living through not one, but several ongoing disasters to which we have somehow adjusted. The current media coverage drowns its consumers through all possible platforms with fake news, sentimentality, and political or corporate agendas to the point in which we feel absolutely everything is going wrong — we are hyper-aware to the point of numbness. The world’s been ending since I can recall, and everyday seems to end a little more.

“It’s paradoxical how quickly we adapt to suffering.” Compassion fatigue is peaking, but also indifference. The news reports that include death graphs, discussing burnout, the declining economy and climate change are the sounds to which many people wake up and go to bed. There is a quote that made me critically rethink how the COVID-19 pandemic has been dealt with not by the political leaders of the world, those in “power” but by everyone else:

“Often, when something bad happens, I have a strange instinctual desire for things to get even worse,” Gabbert writes. “Of course, my rational mind knows better; it knows I don’t want what I want. … Who can say it doesn’t have influence? The secret wish for the blowout ending?”

Is she right? Is our lack of real cooperation to end this pandemic rooted in our secret wish to push a limit, to witness the compliance of everyone into having a new and terrible spectacle? To have something collective to remember in the future?