In 2015, after Satanists threatened to hand out their own literature, public schools in Orange County, Florida banned Bible distribution. I know this because I attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) Sep. 17 Constitution Day event, which featured voter registration, free pocket-size U.S. Constitutions, a platter of red, white, and blue mini-cupcakes, and a table full of banned books. People mostly gravitated to the latter — a motley array whose titles included “Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out,” “Maus,” “The Handmaid’s Tale,” and “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.”

According to Ned Marto, writing lecturer in the liberal arts department and reference and instructional assistant at SAIC’s Flaxman Library, the event’s purpose was “to bring visibility to books and events oppressed by institutions or presidential administrations. When banning books, institutions cite terms like ‘offensive’ and ‘inappropriate,’ terms which are very malleable — attempting to establish objective definitions of what they mean.”

Marto pointed out that the Bible is an interpretable text, one whose meaning and contents shift depending on the historical moment. “Ever since its inception, it has been edited and annotated,” he said. “What’s been passed down over the centuries are a number of different versions of the same book, where a number of things are changed or completely excluded.”

There’s an obvious parallel here with the U.S. Constitution, a legal text. According to Colombian-born constitution aficionado Daniel Jimenez (MAAAP 2020), U.S. citizens often treat it like gospel.

“It’s very interesting to see how the American Constitution is perceived these days,” he said. “Nowhere else in the world is it treated like so sacred a text.” As part of a broader interest in human rights, Daniel has read the U.S., Colombian, Spanish, Argentine, Peruvian, and Mexican constitutions.

“If you track the evolution of other constitutions throughout the world, they are not treated like sacred documents, they are treated more like living documents,” Daniel told me. Which country’s constitution would he say is most adaptable? “The British constitution is not written — it doesn’t exist. Or the Swiss constitution, which is a group of documents from different states. Neither are fixed documents.”

Daniel picked up a copy of the pocket-size Constitutions available at the table. He said he’d never encountered any country’s constitution being disseminated this way. He pointed to the back cover, headed by the hyperbolic: “Get to Know the Most Important Legal Document Ever Created!”

Zemaye Okediji (MA 2020, Art Therapy) agreed that she rarely encountered the Constitution outside of worshipful contexts. “The only other places where I feel like I encounter the Constitution are museums,” she said. “But this is bite-sized, approachable,” she said, referring to the little volume.

She vowed to read it, adding, “I’m more curious now. I’m thinking more critically. My art therapy program is very social justice-oriented, which makes me question things. It’s not just, ‘This is what I know to be true,’ it’s, ‘Why are things this way?’” Comprehending the Constitution, she suggested, would be a way to better answer that foundational question.

Marto, one of the few people I spoke to who had read the entire Constitution, echoed this, remarking how it’s “incredibly shocking how much the Constitution structures our reality, our lived experience. It establishes parameters for a regular social experience.”

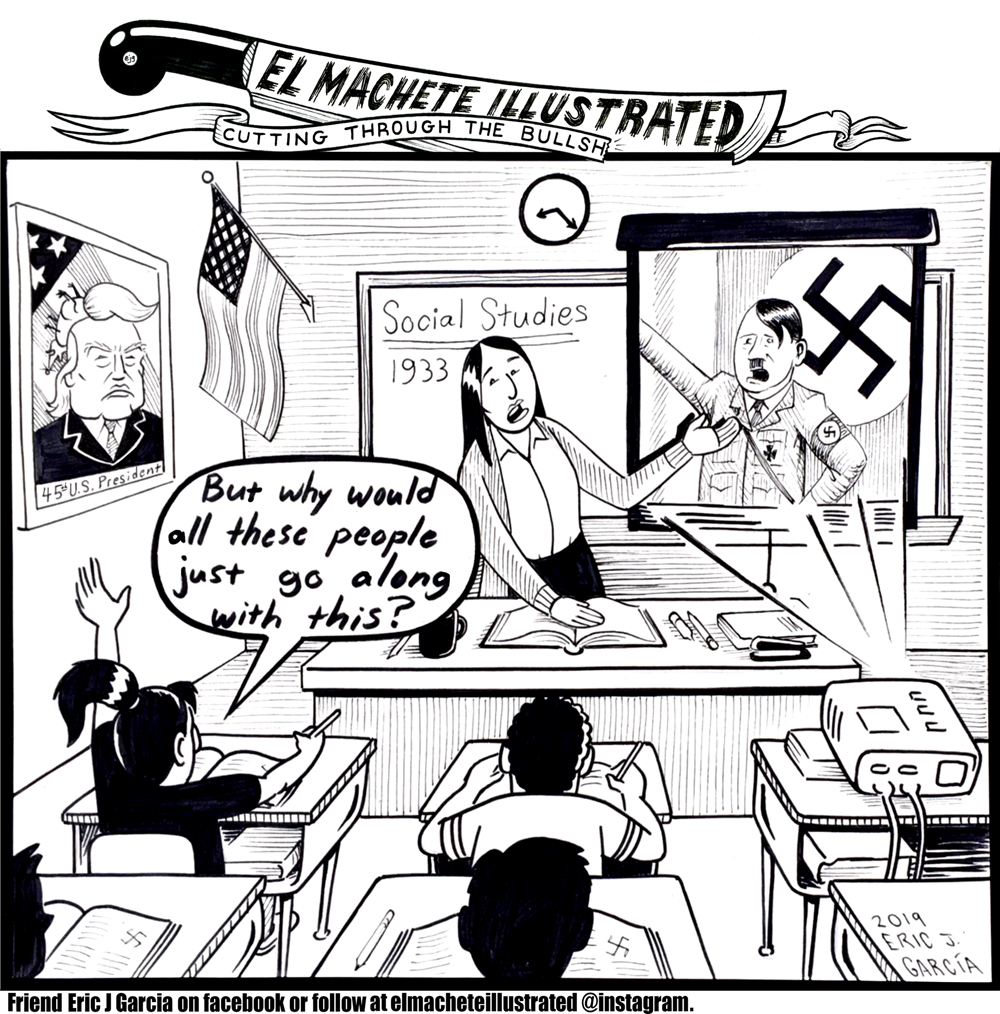

As with many national holidays, the concept of Constitution Day feels strange in a contemporary context. Similar to Thanksgiving and Columbus Day, it has an air of patriotism of which we are increasingly suspicious. We know how fine a line there is between patriotism and nationalism, between belief in shared values and overzealousness.

Also, many of us don’t think about the Constitution until it’s weaponized: invoking the Second Amendment to shoot down gun legislation; the Fifth to conceal incriminating secrets; the First to defend speech and actions that straddle the boundary between discourse and hate.

“How do you measure hate?” Zemaye reflected. The answer is as urgent, and unclear, as ever.

Outside reinterpretation of key Amendments, people know of, but don’t actively consider, the Constitution’s role. “I thought about the Constitution a lot as a seventh and eighth grader when I had to take tests on it,” said Wayne Tate (BFA 2020), Marto’s Flaxman counterpart. “Since then, when it’s not in the news, it’s been very distant.”

Wayne takes a class led by Dr. Eugenia Cheng which interrogates our educational systems. According to Dr. Cheng, modern pedagogy has its roots in a time when literacy rates were low, so teachers would stand up in front of a class and read books to illiterate students. Because literacy is now nearly universal, Wayne said Dr. Cheng argues that “the entire education system needs to be dismantled and rebuilt.”

“I think about the Constitution similarly,” Wayne said. “I read an article about the diction of the Constitution, which basically asked the question of who America was written for.”

Indeed, reading the Constitution is heavy lifting, in large part because it’s a legal document, and legal texts make for notoriously dull reads. Additionally, the President, Vice President, and other high-ranking officers are always referred to as “he,” an unsavory reminder of this country’s historical patriarchy.

“It deserves a rewriting,” Wayne said.