On the fourth floor of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), a bold white text affixed to the museum’s windows announces the space as a “City Hall,” in quotes. A black flag in the same sightline as “City Hall” demands that viewers “Question Everything,” again in quotation marks. These invitations, part of Virgil Abloh’s first museum retrospective, “Figures of Speech,” attempt to speak to Chicago, particularly Chicago youth. With the trendy streetwear that marks Abloh’s public career featured prominently in the gallery, the exhibition is replete with appeals to younger Chicagoans. But beyond the objects within the exhibition there is also an invitation. A public call for Chicago residents ages 14 – 21, the Design Challenge, invites contestants to submit a work via Instagram that responds to the prompt to “take something boring or broken and turn it into something extraordinary.” The winner will become part of Abloh’s exhibition by being featured on social media attached to “Figures of Speech,” and will also be part of a video to be displayed near the exhibition.

Much of the exhibition’s PR focuses on Abloh’s own Chicago connections. Raised in Rockford, Illinois to Ghanaian parents, Abloh spent much of his youth coming into the city and engaging with both streetwear and high fashion. During a press preview discussion with curator Michael Darling, Abloh noted that just walking along Michigan Avenue he could pass an H&M and a Prada if he walked far enough. The MCA also paints Abloh’s career shift from architect (Abloh graduated from the Illinois Institute of Technology) to fashion designer and creative entrepreneur as a whirlwind of talent. Having been named to Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People list in 2018, and having held titles like Artistic Director of Louis Vuitton’s wear collection and Chief Executive of Off-White, Abloh seems like Renaissance man of the year.

The title wall for “Figures of Speech” reflects the breadth of Abloh’s cultural influences. The images on the title wall, a collaged mural, collides portraits of Marc Jacobs, the golden arches of McDonald’s, and the smoking Twin Towers on 9/11. This cultural autobiography sets a tone of immediacy to the exhibition. Abloh’s interests in popular culture and the omnipresence of consumerism are amplified from the beginning.

Inside the galleries, Abloh’s work is displayed on crowded bright blue racks (which hold garments from his signature collection Off-White to the tutu tennis outfit he designed for Serena Williams) and stacks of records (the album covers mark the first time the digital concert posters for his DJ endeavors have made it to 3D) intermixed with colossal billboard sculptures and high-definition photographs. Taken together, these seem to scream, “Is there anything this man can’t do?!”

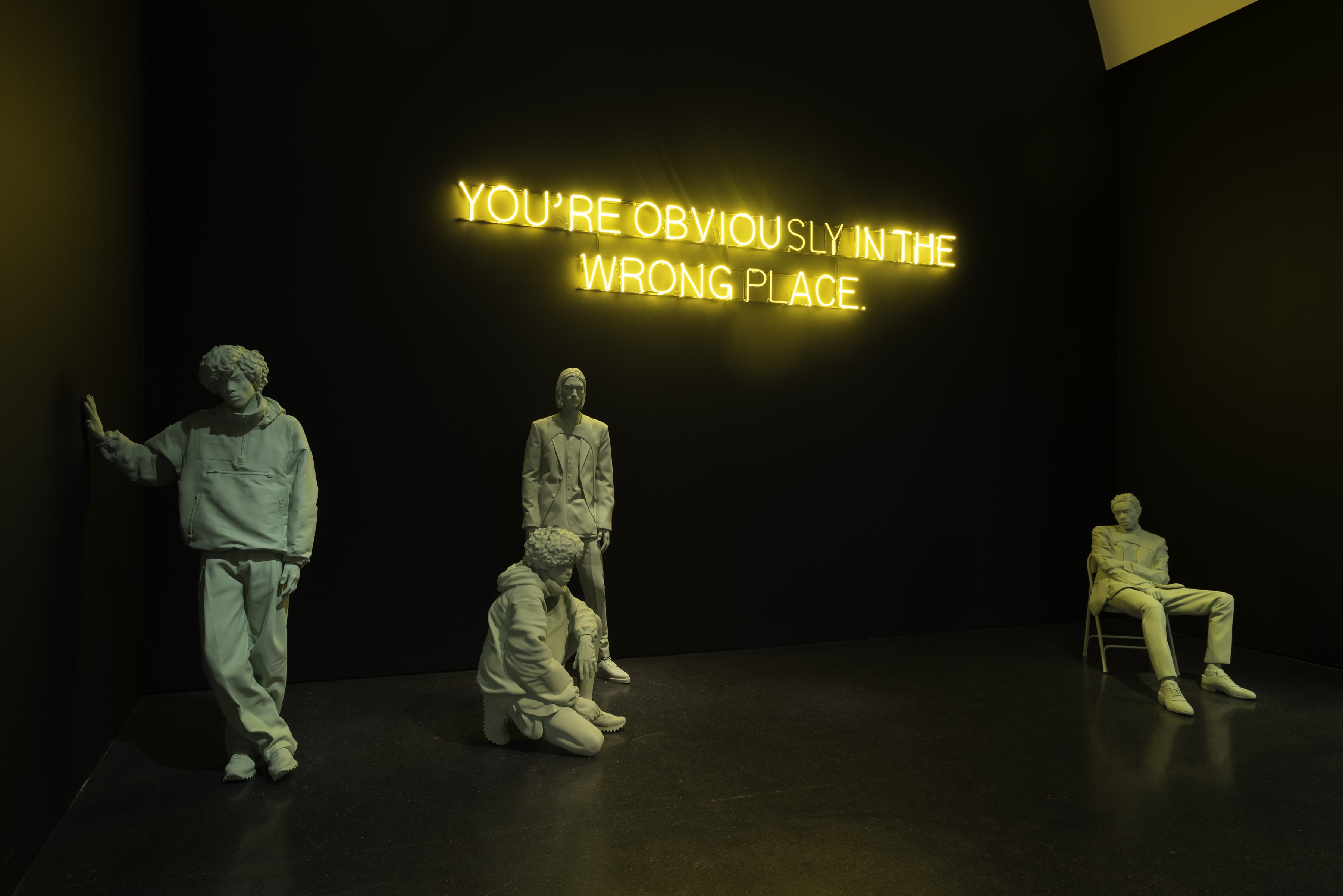

. . . Maybe address his ties to politics. Kanye West, an outspoken advocate and friend of Donald Trump, is a key collaborator for Abloh, who worked on the Yeezy album cover (an enlarged version appears in the exhibition’s ‘Music’ section) as well as at DONDA, West’s production company. In addressing their collaborations during the press preview, Abloh neglected any mention of West’s support of Donald Trump. This part of Virgil’s network comes into play with the “Black Gaze” section in the exhibition, which explicitly grapples with “the black cultural experience.” Nuance unfolds in the last section of the exhibition, ironically titled “The End” to emphasize the tongue-in-cheek use of quotations throughout the exhibition. The centerpiece of the room is Arthur Jafa’s “Screen Shot” (2017, printed 2019), a screen-shot of a conversation between Abloh and rapper Theophilus London, which nods to the communities Abloh is woven into. This work by another artist in Abloh’s retrospective also gestures towards the racial politics in Jafa’s video, “Love is the Message, the Message is Death,” currently on view on the first floor of the MCA.

Despite my criticism of Abloh’s silence on Kanye in the exhibition, I’ll concede he has a knack for subverting the commercial to address his own political leanings. In “Cotton” (2019), he appropriates the icon of Cotton Incorporated (you’ve seen the image of the two letter T’s in the word ‘cotton’ growing together into a cotton plant on the collar of your white t-shirts or on the inseams of your underwear), placing the graphic on a roughly painted black background so that the ad is made in white lettering rather than its usual black text on white fabric setting. This reversal of the usual image addresses slave labor in the cotton trade and the ways in which white Americans continue to benefit from black labor. Speaking on the larger themes present in “Figures of Speech,” Abloh said, “Any time an idea takes shape on a particular surface — a photo print, a screen, a billboard, or canvas — it becomes real.” Not only might it make the image real, but it makes history a more visualized presence in this exhibition.

The exhibition circles visitors around to an exclusive pop-up shop that Abloh titled Church and State (only museum visitors have access, unlike the main street level MCA shop, which is open to the public). The explicit exclusion of commerce in the title of the storefront equation makes it feel implicit in both the spiritual and the legislative. Though I’m not convinced by the claim to offer a variety of price points in the pop-up (the boutique MCA price tags I picked up ranged from $344 – $724), I have to concede that there is a certain creative quality to Abloh’s take on consumerism. Abloh finds the seductive quality of designed objects and the desire to move from consumer to producer as intertwined in his practice. He likens searching for a shirt for yourself that matches the one you saw a favorite celebrity wear on TV to a creative practice. One can interpret this as a consumerist curation of the self that falls flat when held to theories of original artistic genius. But in Abloh’s terms, finding that exact shirt to purchase can be likened to the observing, making, looking, and collecting of the lofty commercial ambitions of the art world with artists, auction-houses, and collectors who follow gallery trends. Abloh, in this scenario, is a trendsetter of the highest caliber.

Beyond the walls of the museum, inside the Vans storefront on the corner of State and Monroe, another rarefied collection is on display: decorated sneakers and slip-ons are set in vitrines atop columns with surface design that reads “Custom-made for YOU.” This limited time display, objects from “longtime collector” Bill Cruz, originally struck me as gimmicky the first few times I passed it. But after spending time in Virgil’s church, I’m more convinced that the lines between consumer and creative are blurrier than we make them out to be. There is room to be both a tourist and a purist. The act of selling may be a publicity stunt, but there’s something to be said for the seductive form of the window display.