American photographer Laura Aguilar’s images can be read from multiple lenses to explore her constantly intersecting identities: large, queer, and Latinx. But their real triumph is, first and foremost, in their power to tell a story. That is what the late artist’s first major retrospective, “Show and Tell,” on display through August 18 at the National Museum of Mexican Art, ultimately accomplishes: a narrative of a woman who gradually grows more empowered by her own existence through the act of self-representation.

Viewers unfamiliar with the photographer’s work will likely be surprised with how it progresses throughout her lifetime. Aguilar, who died in April 2018 at age 58, grew up in heavily Mexican East Los Angeles. Mostly self-taught, with some studies at East Los Angeles Community College, her work has been shown in museums and galleries all across L.A., including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Vincent Price Art Museum, and the Hammer Museum. Her photographs would eventually be shown all over the country and internationally, finding their way to Mexico, Spain, Germany, and the 1993 Venice Biennale.

No matter how far it reached out, Aguilar’s work always stayed rooted in East L.A., as can be seen in “Intersections,” a series of her initial photographic work. In those portraits mostly taken in the 1980s — a group of long-haired young men who call themselves “The Ilegales” standing under graffiti, a woman in a traditional blouse posing in front of a table full of crafts, a man fading away while lying down on a bench — it is already possible to see a community as documented by someone who walks down the same streets that they do, who knows their issues because she lives with them as well.

Her work transitions into a more specific community with her sets of portraits of regulars at L.A. lesbian bar “Plush Pony,” as well as her “Latina Lesbians” series. Both series comprise Aguilar’s contribution to this group’s visibility. The first shows brown women in couples or groups; in front of a makeshift studio background, one woman confidently poses with her hands on her belt buckle; a couple hugs and smiles at the camera; in a more candid shot, one woman lifts another’s leg.

In the latter series, which was commissioned by a mental health conference, Aguilar pairs the portraits with written quotes by each subject, thus granting them agency to accompany their image with their own words. “I met a Morenita who touched the core of my heart,” writes a woman who clutches her chest in surprise in her portrait, and who signs as Cookie (she uses two woman symbols in lieu of the O’s). “I used to worry about being different, now I realize my differences are my strengths,” says Carla, comfortably sitting on her couch while dressed in a suit and tie, a cigarette between her fingers. Aguilar also includes a self portrait, a picture of her smiling while donning a cowboy hat and standing in front of a Frida Kahlo print. Under the image, her text reads “Im not comfortable with the word Lesbian but as each day go’s [sic] by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA.”

This leads up to one of Aguilar’s most powerful images, and the first one where she explores her own naked body: “Three Eagles Flying.” The image shows Aguilar standing in the middle, flanked by the flags of the two countries into which she splits her national identity: the American one on her right, the Mexican one on her left. The national birds of both countries are eagles, and the meaning of Aguilar’s surname comes from the Latin word meaning “place inhabited by eagles.” Another Mexican flag covers Aguilar’s head, with the central emblem’s eagle right on the face of the photographer, who covers her lower body with another American flag. Over her torso, which remains uncovered, is a rope that also binds her hands and wraps around her neck. Despite what the title suggests, she is far from the air, trapped by and between the two other eagles in the picture. She is smothered by one nation, and constricted by the other. She is an eagle with no nest.

As uplifting as Aguilar’s work can be in terms of representation and empowerment, it would be naïve to ignore the very real struggles she went through in life. She was born with auditory dyslexia and lived with clinical depression, a part of her life that is explored in the series “Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt You.” In this four-part piece, Aguilar again pairs images and text, this time alluding to her depression. “You learn you’re not the one that they want to talk about pride,” she writes under a picture of her holding a gun. In the next shot, she puts it in her mouth.

After viewing these images, it is a contrast to see Aguilar’s first fully nude self-portrait, “In Sandy’s Room.” In it, Aguilar sits next to a window in front of a fan, an iced drink in her hand. Her eyes are closed as she attempts to escape the heat. In an otherwise trivial scene, her large body unapologetically takes up space, becoming a powerful testament of self acceptance. In the face of an art historical canon so dominated by nude, objectified women — Manet’s “Olympia,” Goya’s “Maja Desnuda,” or Picasso’s “Demoiselles d’Avignon,” to name a few — it is refreshing to see a nude portrait as far away as possible from the male gaze, one in which the artist truly reclaims her body.

The celebration of self love in the face of vulnerability extends to a wider community in the series “Clothed/Unclothed,” where Aguilar photographs couples, families and groups of friends of different sizes, ages, ethnicities and sexual orientations. Each diptych shows the subjects clothed on the left frame and nude on the right one as they hug, kiss, and lean on each other. Apart from the absence or presence of clothing, the pictures on each side are not too different from each other, both showing people comfortable in their own skin.

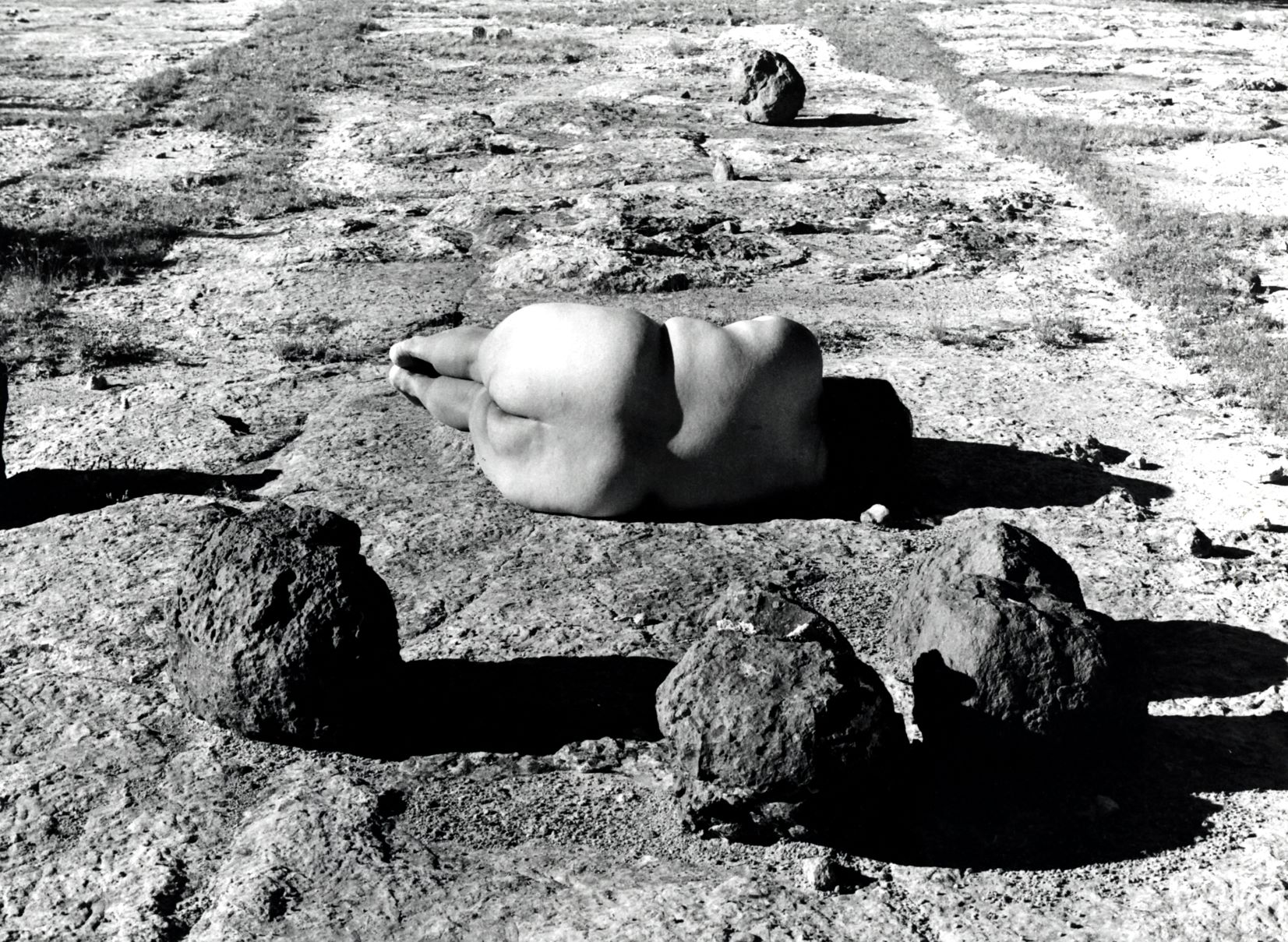

With this feeling, the exhibition appropriately segues into Aguilar’s series “Landscapes,” from the late 1990s. While “In Sandy’s Room” shows the photographer fully nude in an intimate, interior, scene, “Landscapes” moves further in that direction, as she poses unclothed outdoors, interacting with nature. This is the most unapologetic she gets, as her nude, large body blends with rocks, tree branches, and fallen leaves. She even nods to Narcissus in an image where she contemplates her own reflection in a pond. In another picture, Aguilar sits cross-legged on a massive boulder, her eyes closed in meditation. She seems to have found her inner peace. The third eagle can finally fly.

Laura was one of my dearest friends and housesat for me in my Pasadena bungalow summers – She was fun and a picky eater, she had so much compassion for my autistic son as he grew up, much more than anyone else… the best story was when an art tour showed up to her aunt’s modest home where she lived in Rosemead, California. The Chinese neighbors peeking as the Germans marched out of the bus taking photos …