The homeless man-robot hobbles around on crutches in a bloody and torn Uncle Sam outfit, his eyes blazing with a hellish light. He is, of course, a specimen of contemporary art. In the opening scene of art world horror movie “Velvet Buzzsaw,” which was recently released by Netflix, the patron class flits by at Art Basel Miami, pausing for a closer look at the grotesque caricature of poverty. This isn’t an exaggeration of the contemporary art world: The biggest crowd of selfie-takers at the fall 2018 Art Expo Chicago was circled around a lifelike sculpture of a homeless man stretched out in a sleeping bag on the floor.

The evil art in question is the estate of Vetril Dease, who lowly but ambitious gallery attendant Josephina (Zawe Ashton) discovers dead in their shared apartment building. When she starts poking around his flat, which has conveniently been left unlocked, she finds a lifetime of paintings stashed away. You might expect the haunted masterpieces of an evil artist to look something like the work of Ivan Albright, Otto Dix, or pre-filmmaking David Lynch, but Dease’s style is deeply unremarkable: It’s just basic bitch figurative painting. This joke never gets its punchline, it just hangs out in the background of the film.

Josephina uses her discovery to rise in the ranks of the art world, becoming partners with her former boss, the cunning gallerist Rhodora (Rene Russo), who rules with a Miranda Priestly-like grip and looks eternally 67 going on 37. The characters are as two dimensional as works in a flat file. There’s Morf Vandewalt (Jake Gyllenhaal), an unrealistically powerful art critic who Josephina begins dating; an art handler (Billy Magnussen) who wants the world to know that he, too, is an artist (he made that painting covered in Fruit Loops); and various other conniving gallerists.

We learn that Dease’s family burned to death under mysterious circumstances. His former co-worker ended up dead with a knife in his back, and that signature dark brown pigment he used is blood (“his own, presumably,” the archivist says, after a dramatic pause). But everyone is already losing their shit for Dease, and the collectors, with a little cooking the books to increase its value, are lining up to take a work home. Skipping any escalation of creepiness, characters then start dying off one by one in gory, visual culture-themed ways. Since the paintings do some, but not all, of the actual killing, and other previously unhaunted art objects also do some of the killing, these demises only occasionally move into the orbit of the plot’s logic.

“Velvet Buzzsaw” wasn’t made by and for art people, and its primary purpose is not social critique. So it’s surprising how much satire it gets right. Some artists, once established, are just as beset by self-doubt as when they started out: Piers, a washed-up artist played by John Malkovich, stares forlornly at the lone mediocre painting he’s managed to make in the past year. Gallerists are people who sell products, and the products just so happen to be art. In the upper echelons, there are tight corners in which to date or change jobs, and when people go to openings, they never talk about art, they just talk about who is fucking whom. There’s no shortage of ranty texts and malformed artworks railing against the market and social mores of the art world, but it’s interesting to see these critiques lobbied in a film made for a much broader audience — the 150 million or so Netflix subscribers.

Dease’s life history takes cues from Chicago outsider artist Henry Darger, a reclusive hospital custodian who created a 15,145-page-long epic in secret. It wasn’t discovered until shortly before his death by his landlords, Nathan and Kiyoko Lerner, who went on to oversee his estate. Darger’s work was bizarre — in his pastel-colored landscapes, the young girl protagonists, most of whom are intersex, are being hung or strangled by the men who pursue them — but he was no murderer. Darger saw himself as a protector of children; it is speculated that he suffered from abuse during his time at a youth asylum. Dease, on the other hand, is thoroughly demonic. The assumption that outsider artists or people with mental illness are miserable and murderous is one of the attendant stereotypes not of artists, but of the mentally ill in a society where funding for social services is constantly being cut.

This weird nexus between art and evil is creepy because it’s so far from the idealistic assumptions we foist on art. When art is not transcendent but cursed, it implies some deep chasm in the moral fabric of society at large. Hence “The Picture of Dorian Grey,” the obsessions with Hitler’s art, and, for that matter, George W. Bush’s. The highest, most dewey-eyed aspirations of art as a shared human language, the best and finest secretions of culture and progress, are here upended.

If there is a lesson, it is that greed and ambition corrupt. Just about everyone gets the Dease touch. The exceptions are Damrish (Daveed Diggs), a street artist who must choose between his collective and the gallerists who promise to make him a global sensation, and Coco (Natalia Dyer), a 22-year-old from Michigan with an intern-like aura of permanent cowering. Moral of the story: If you wish to avoid death by giant interactive mirror ball, join a collective or be from Michigan.

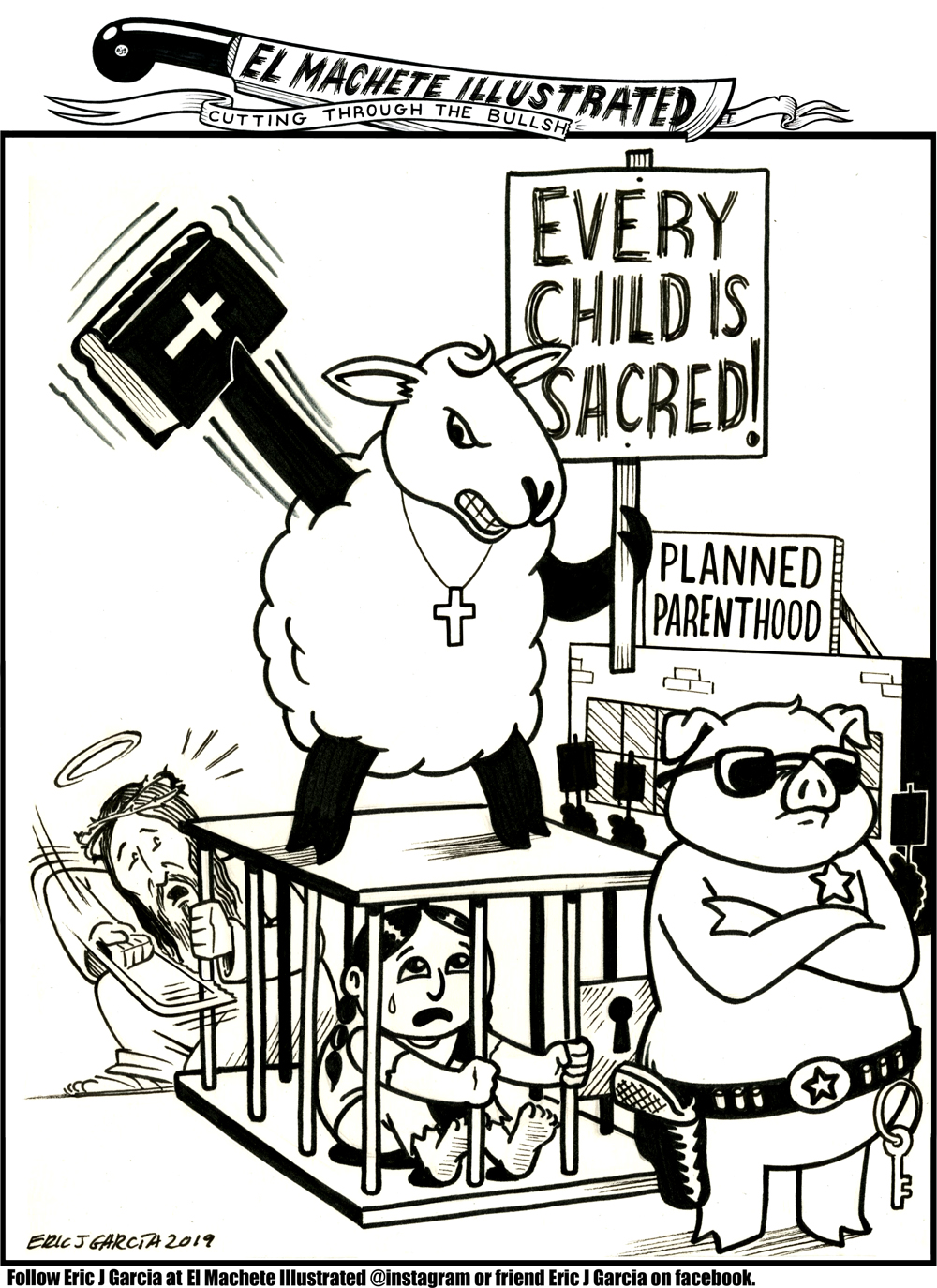

“Velvet Buzzsaw’s” skewed depiction of culpability is the most glaring misrepresentation of the art world. Gallerists, critics, and blue-chip artists may loom large in name, but they’re never the primary powerbrokers of the art world. The nexus between art and evil exists, but the real power, and the real greed, can be traced back to the ultra-wealthy who sit on museum boards. Warren B. Kanders, for example, vice chairman of board of trustees at the Whitney Museum, has an estimated $700 million net worth. He’s also CEO of Safariland, the defense company that manufactures tear gas used on immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. There is real horror in the art world, but it’s not juicy enough to fill 90 minutes of Netflix pulp. And besides, a fable about art and evil set in the Sackler Wing of the Met, or the boardroom of the Whitney, or the stalled construction site of Guggenheim Abu Dhabi wouldn’t be a horror movie. It would just be straight reporting.