Square-block characters, ink drawing and painting, Post-Mao discourse, Eastern religious icons, media censorship: These are a sampling of the cultural identifiers which, while recognizable in many Chinese students’ artwork, hardly factor into their critiques.

I’ve had people ask me what it’s like for us — the international students — to experience a critique in which cultural signifiers go unrecognized. When trying to answer this question, which probably requires some detailed and vivid description with my emotional investment in the topic, I hear a voice reluctantly telling me: You have to articulate that such a critique is not something to overcome, but to compromise on.

In other words, knowing critics won’t recognize certain cultural signifiers means avoiding or modifying them in our artwork. Hearing friends and peers with the same cultural and political background talk about compromise during critiques has become commonplace. As a Chinese student, I find this kind of dialogue constructive. But it tends to happen privately, outside of the classroom, among ourselves: a minority student group which, because of its shared heritage, understands the trickiness between Chinese and American cultures.

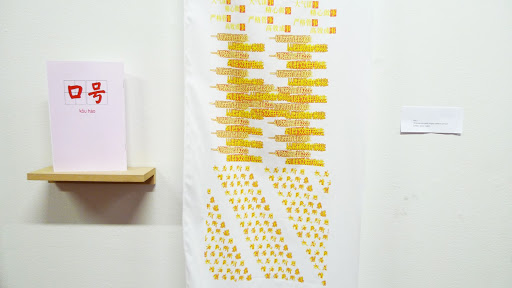

I began thinking about this issue after seeing a class critique a project made by Abi Li (BFA, 2021), a Chinese student currently focusing on fiber. Li’s piece, “Kouhao” (口号, meaning “Slogan”), is a scroll of Chinese character-based patterns printed on cotton cloth, vertically hung on the wall of the exhibition space, accompanied by a small booklet explaining the propagandist nature of the language. This work plays in between its cultural specificity and visual generality. By transforming Party slogans into mechanical and repetitive visual schemes, Li undermined the messages’ content.

While Li was making this work last Spring, China was undergoing political turbulence. This drove Li to adopt a political device as the subject of her artwork, and to present it with a jocular twist. The slogan Li reproduces is one of the most pervasive reminders of authority in Chinese citizens’ everyday life. It is a fundamentally aesthetic element, completely ubiquitous. Officials post the slogans on walls, in schools, hospitals, cinemas, parks, sidewalks, train stations, airports, even the Four Seasons Hotels. Li’s choice to arrange the slogan into rigidly repetitive patterns was her way of criticizing a highly naturalized social phenomenon.

In her own words: “Anyone who has lived in mainland China sees these slogans everywhere. They kind of become memes. Recently these slogans have been posted even more densely and aggressively. So, people eventually get used to them. They became invisible because of their ubiquity, but they are unconsciously polluting our nerves…”

Because we share a cultural heritage, her explanation made perfect sense to me. I was then curious to hear how she handled the slogans’ translation, given that the words are often ambiguous and encoded with political reference based on Party doctrine.

Her answer reveals our shared dilemma. Since it was impossible to have the class understand the trickiness of such language at once, she chose not to translate everything, instead opting to emphasize the phrases’ visual impact. One set of her chosen phases literally translates to: “Strictly manage the Task. Efficiently accomplish the Task.” 事 (shì) means matters, stuff or task. This character is frequently mentioned in the propaganda slogans posted around government buildings and elsewhere. So, 事 abstractly references tasks and duties that are serving for the greater good according to Party values.

Even to Chinese citizens, the slogans’ absolute meanings are fluid and cryptic. It would be doubly (at least) challenging to relay their meanings to non-Chinese citizens. So, Li compromised, opting for an altogether different artistic approach.

A class critique with a diverse set of contributing voices is a great advantage of our school. However, this aggregation pushes many international students to produce work which communicates their messages in broad, non-specific ways. The brief forty-five minute critiques also require students to omit culture-specific explanations.

That said, compromises, adjustments, and sacrifices will always be made. Many students — international and otherwise — make sacrifices for the class critique, and what has been sacrificed is not brought up afterward. Abi Li sacrifices the cultural specificity of the slogan language itself, instead dedicating the rather general visual language to the whole class for the sake of critique.

Cold reading, a common critique method, often expands and liberates commentary flow, but is detrimental when it comes to a student presenting a work characterized by their cultural-political identity. This affects international students most acutely. Although I’m aware of how compact undergraduate class critiques are, I believe the critique procedure should be more flexible. Instead of setting a rigid, universal process, a student should have some liberty to choose whether they want to present a contextual introduction, or start with cold reading.

Oftentimes, I hear Chinese students say: “You can’t do anything about it,” when describing China-specific critique situations. This phrase’s passivity may frustrate listeners hungry for more active protest. But when we say, “You can’t do anything about it,” what we really mean is, “I wish I could.”