Shortly after the installation of Hans Haacke’s “Gift Horse” on the roof of the Art Institute of Chicago, I saw the artist in conversation with Ann Goldstein, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Susanne Ghez, Curator of the exhibition. Haacke looked like a happy but recalcitrant old gnome, slightly uneasy about being the center of attention. The conversation progressed in fits and starts through all the mundane details of how the sculpture was brought to completion: How the visual reference for his monumental bronze skeletal horse was an engraving by equine artist George Stubbs, apparently chosen for its aesthetic appeal and because Stubbs lived at the same time as Adam Smith; how Haacke decided to enlarge the horse’s skull slightly so it would appear proportional to a viewer one third its height; its harrowing installation by crane on the roof terrace of the museum. But when the conversation shifted toward the meaning of the work or the artist’s purpose behind it, Haacke, smiling with some combination of mischief and shyness, evaded providing a direct answer. He preferred, he said, to leave the viewer to form their own conclusions.

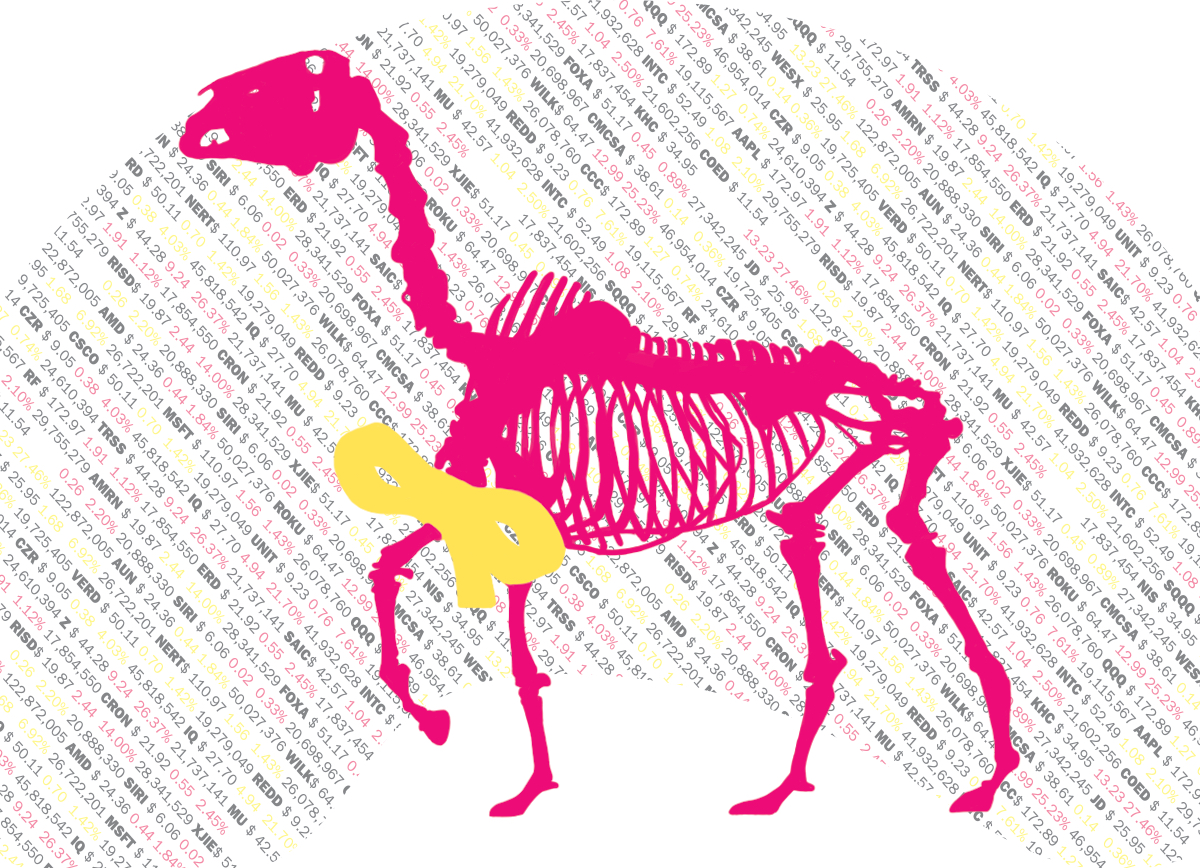

When I visited the sculpture on the roof of the Art Institute of Chicago one afternoon in mid-December, the gibbous moon was visible just above its tailbone. A museum guard eyed me from the other side of the glass doors. There was no one else on the terrace. In the early winter dusk, the sky was a mauve that approximated the grey of the horse’s base. The skeleton is very big; at more than fifteen feet tall, it towers from the top of its plinth. The viewer isn’t even eye level with its hooves. Tied around the horse’s delicately raised front leg is an LED ticker tape in the shape of a giant bow. The screen displays stock exchange prices as they are updated in real time, the business names gliding along the curves of the bow in and out of sight: McDonald’s Corporation, Intel Corporation, International Business Machines Corporation, Goldman Sachs Group, Johnson & Johnson.

The ticker-tape is a gesture toward an economic reality, but one which, for all the specificity and precision of the stock values, remains so vague as to convey no meaning at all. When installed in Trafalgar Square, the ticker streamed updates from the London Stock Exchange; there is no information in its Chicago setting as to which stock exchange the ticker tape now shows. And yet, a mandorla of assumed edginess surrounds the sculpture. When it was first displayed on Trafalgar Square’s empty fourth plinth, British art critic Waldemar Januszczak described the sculpture as “like letting Trotsky loose on Buckingham Palace.” If this is considered institutional critique, then institutional critique has become a method of talking around capitalism and the museum without stating anything new, relevant, or remotely interesting.

Haacke’s “MoMA Poll” is one of the first pieces of what came to be known as institutional critique, artworks that lay bare the connections between the market and arts patronage or the inner workings of the museum. In the decades since, Haacke has continued to work with site-specificity to tie funding and politics to the art world. The descendents of this work are the research-based projects undertaken by artists and artist collectives to document some social phenomena. Haacke’s influence is also visible in works that trouble the presumed democratic ideals embodied by museums as places of accessible learning; In Tania Bruguera’s 2008 “Tatlin’s Whisper #5,” two mounted policemen used crowd control techniques to herd visitors to the Tate around the museum lobby.

But Haacke’s most interesting work was poignant because of the specificity of its references. “MoMA Poll” referred to a patron of the very space in which the poll was conducted, as well as to an issue (the Vietnam War and Rockefeller’s likely campaign for president) that was urgent at the moment of the work’s display. Although time is indicated by the sculpture in the form of the real-time updates of the stock market, there is nothing that lodges a critique of its own specific being.

It is in this respect — the inability of “Gift Horse” to name its exact relationship to particular corporate funders — that sets it apart from much of Haacke’s other work. Like any other sculpture, it can be displayed in a string of art spaces. Without its site specificity, institutional critique loses its potential edge. During his artist talk, Haacke said its setting on the roof of the Art Institute, with the skyscrapers of the North Loop as the sculpture’s backdrop, was important to granting it a new meaning. But this faith in its setting seems to be a convenient justification for treating it like most other art objects. It can be shown in any art space, anywhere in the world, at any time. Even when referencing its specific place and time, institutional critique is wholly reliant on being displayed inside of a gallery space in order to make its point. It is as reliant on the museum as any ostensibly depoliticized artwork.

There is nothing in “Gift Horse” that points to either its own creation — the source of the bronze, wood, and paint — or the coterie of assistants and art handlers who safely installed it via crane on the roof of the museum. It is exhaustive and deeply unsatisfying to try to imagine a documentation of the labor put into producing this sculpture. But if it is meant to be a provocative remark about capital, the near-impossibility of this task is what makes it urgent. There is no pure message about the market that is not also immersed in the market itself.

In September, at about the time “Gift Horse” would have been in transit, workers at 26 Chicago hotels went on strike to demand year-round health care coverage. Hotel workers are often laid off each winter, when business is slower, and are left without health insurance. Several blocks north of the Art Institute, doormen, housekeepers, and other staff marched in tight loops in front of the Ritz Carlton, chanting and drumming. The Ritz Carlton is just one of the many hotels and casinos owned by Neil Bluhm, the donor behind the Art Institute’s Bluhm Family Terrace, where “Gift Horse” stands.