“I happen to like shooting first,” a direct quote from the 1970’s series “The Han Solo Adventures” by Brian Daley.

I began this article after watching “The Last Jedi,” the latest installment of the “Star Wars” franchise (before “Solo” — this has taken me a while; also go see “Solo” and tell me what you think). And, after seeing “Avengers: Infinity War,” I’ve been thinking again about the characters I’ve lost. (Oh: spoilers ahead).

Before even “Star Wars” though, I’ve been thinking, generally, a lot about loss. About death. I’ve been thinking about why it is so hard to let go of the things that we love — people, superheroes.

I’ve been finding the difficulty of this task is not at all minimized by necessity or fiction. What is this insistence to defend and then demand time for things that are long-lived, even, outlived, of their usefulness?

The first place I go to research Tahiri Veila, my old paramour and alter-ego (we all have our problems), is not a website I will name here. It is a bullshit website. The character profile reduces Tahiri to cray, but a good lay. Her complex psychology, background, and her tumultuous and fascinating relationships disappear. She is painted as one-dimensional. She is a slutty, fickle blonde whose unstable mental condition is the butt of every joke. A sith whore.

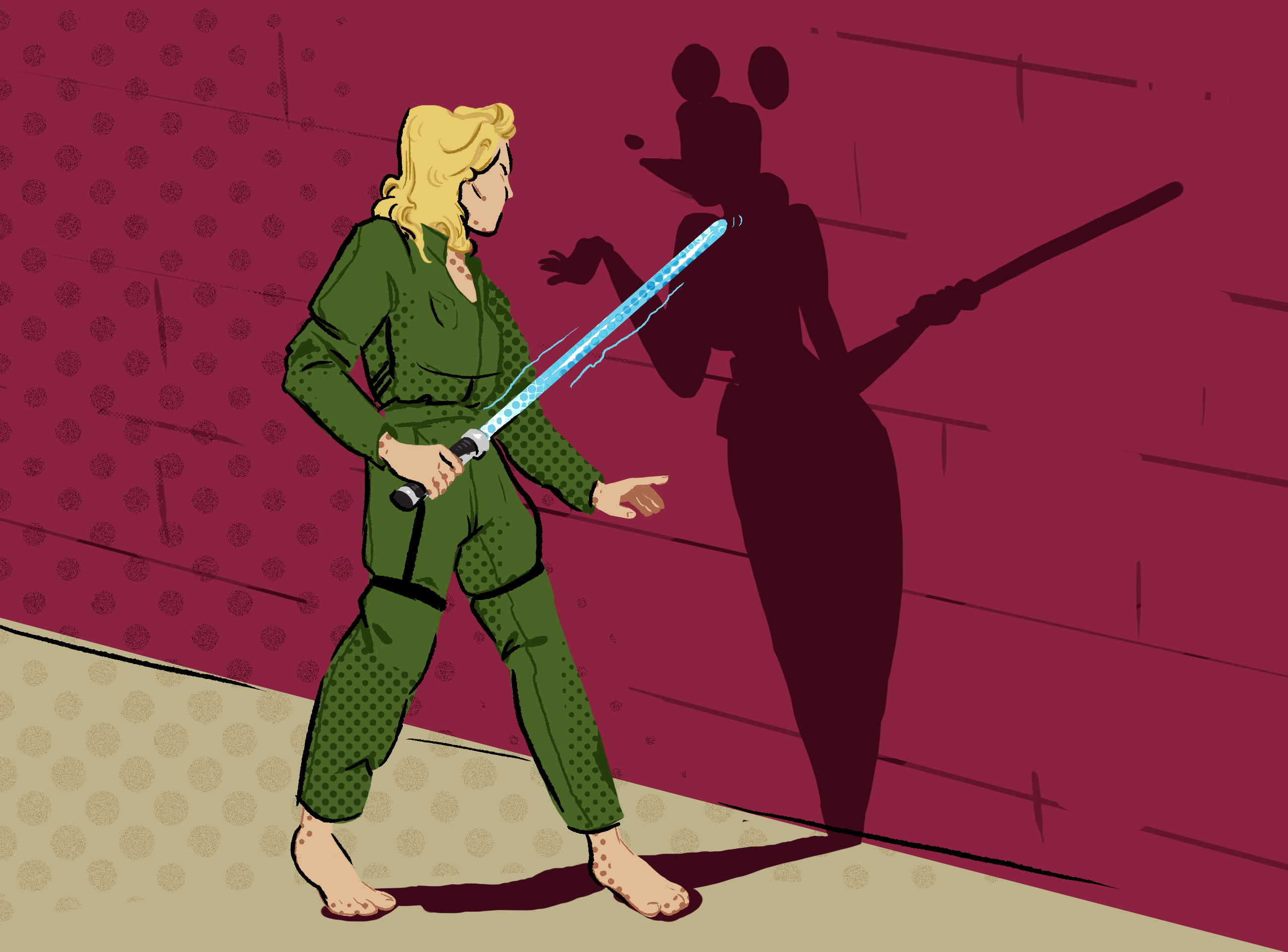

To backtrack, Tahiri was a beloved “Star Wars” character I aspired to be and often imitated in childhood. Tahiri was raised by Tuskan Raiders on Tatooine and brought to the Jedi Academy (run by Luke Skywalker) where she befriended his nephew, the youngest son of Han and Leia, Anakin Skywalker (you can guess whose legacy young Anakin is tormented by). Tahiri always spoke her mind, was sturdy and resilient even through trauma. Most importantly, she never wore shoes.

Tahiri belongs to the Star Wars Expanded Universe (EU), a convoluted mix of various writers’ interpretations of the fictional history initially beget by George Lucas. This is also a culture and tradition that was destroyed when Disney acquired the rights to “Star Wars.”

Yes, you read that right, the Death Star can destroy planets, but Disney can destroy a Universe. Thanos can destroy half a population, but Disney can destroy an entire population. (Who is the villain again?)

This means Tahiri is dead, murdered by corporate greed. No, this means something much worse: Tahiri never even was.

Whenever I would mourn this loss, and mourn it I would — loudly and to anyone who was in earshot — I would be met with what to me seemed like a strange comparison. “Well,” people (read: men) would ask, “do you read comics?”

(Yes, I fucking do, but that’s besides the point I begrudgingly admit they had.)

Timelines in comics are fuzzy, especially in the DC and Marvel Universes. There are often many versions and alternatives. Characters who die will often return.

“The Ringer” published an article detailing the non-Disney history of Han Solo (and it sounds much better to me than the Disney film, minus Donald Glover). Written by Brian Daley in the ‘70s and overseen by George Lucas, these books follow the dark and (as it seems to me) nihilistic young Solo and Chewie on adventures throughout the galaxy. The impression I get from the covers and description is that of a wild west narrative. The good guys and the bad guys might be the same (until, of course, Leia).

“All very well and interesting,” you might be thinking. “Great effort inserting an alternative history that has been buried by commercialization of the franchise. Great job fetishizing the past. But really, why do you care?”

Why — I do wonder — why do I care?

I propose that our ability to care is a muscle. It is not diminished by exercising it but instead strengthened. For an interdisciplinary school like School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), I imagine this theory would fall right in line. A love of painting does not diminish a love of film; in fact the two can work to build each other up. My love of Tahiri does not need to diminish my love of Rey — and my love of “Star Wars” does not need to diminish my love of “The Avengers.”

Similarly, my love of fiction does not detract from my lived life, but instead adds to it. In this way, Disney’s act of murder is felt most acutely. Disney is negating the lived experience I shared with this character. Tahiri accompanied me to slumber parties. She was the skin I tried on during my first round of spin-the-bottle (Lord, beer me strength). She and I spent long summer afternoons hiding in the cemetery. Maybe they wouldn’t find us, and I could catch one more page of her adventures.

It’s true, yes, Tahiri “lives in me,” as we are often told our loved ones’ memories continue on through us after death — but that does not mean she is not also gone. This is not a comic reality, despite some similarities; There was something biting about “The Avengers” finale, almost a mockery. Yes, I cried (that Spider-Man scene, Jesus). But also, the only character I truly fear for is Gamora (which is a whole different article). Even if she doesn’t return though in this timeline, and even if the other characters don’t return either (but of course they will), they are immortalized in comics and films and a host of other media that allow us to interact and live with them again.

Not so for the EU. The few books I have left of Tahiri and Anakin’s adventures are static and isolated within my own imagination, cut off from society at large. On Amazon, my favorite book has only one copy left in stock a measly $1.75 is all it is worth.

And in this way I most sound like a conservative — do I not? Does my lamenting for the past not imitate those of Trumpland? “Make America Great Again,” and the question many of us continue to ask is, when exactly was it great?

Am I implying through my love of Tahiri that this time period in the Star Wars Universe was great? That just isn’t true. I grasped to her because even in a Universe that expanded the role of women, most of them were family, royalty, and almost all of them, including Tahiri, were white. They were still vastly outnumbered by the men, of course, who were also (almost) all white. The stories were those of patriarchy and class warfare and toxic masculinity and problematic sexual politics — and not in an enlightened way. In a way meant to titillate, to prey on our (read: men’s) base instincts.

It is not completely out of left field that Tahiri is known as a good lay, but insane. It is not inconsequential that the site that names her as such is one of the first ones I can find detailing the EU — a site propagating racism and misogyny by white men who disguise their toxicity as “nerdiness.” (But again, an article for another time).

So how do we let go of something problematic while still loving our relationship, the memory? Must we wholly surrender? Must we learn to accept the reality that’s been given to us by the Capitalist Frog Fucker, Disney?

I don’t have answers. I’m sorry if I led you on. I will though leave you with some words of wisdom from “The Han Solo Adventures” — home to a Han as dead as Tahiri.

“These fools, these execs and their underlings, … they’re creating just the sort of climate to make their worst fears come real. The prophecy fulfills itself; if we weren’t talking about life and death here, it would make a grand joke!”

Wouldn’t it though? To ignore these deaths would be to realize Disney’s ambitions. But, to hold onto them, to fight for what is beyond use and lost is to defy to the cyclical joke of life and love and progress. The only truth it seems we can come away with is that Solo shot first — a reality painted over through the years, kept alive by toxic men who need their character darker, who cannot accept nuance and gray, who see all or nothing.