What does it mean to be a “black artist?”

As with most things, much of the answer lies in how we’re defining it, but to many black artists, it has meant marginalization.

In instance after instance, liberal arts colleges have been taken to task for both particular and perceived slights towards their minority students. One side of the coin has to do with all of the usual hangovers from the culture wars: jingoism, class biases, too many Dead White Males. But the other — how these blinkers affect student-to-student relationships, or even student-to-teacher relationships — is harder to gauge.

As of fall 2015, fewer than 4 percent of students enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) identified as African American. The graduation rate for these students is 40 percent — nearly a third behind the retention rates of both white students and of students at SAIC in general. Chalk it up to whatever circumstances you’d like, but it’s worth asking whether both the student body and the faculty are equipped to deal with these discrepancies.

If one reads the mission statement from “De Nue,” a Student Union Galleries (SUGs) arts publication and accompanying exhibition, however, we’re way past that. “As black students in the SAIC community,” the statement reads, “we are constantly combating racism institutionally and interpersonally.”

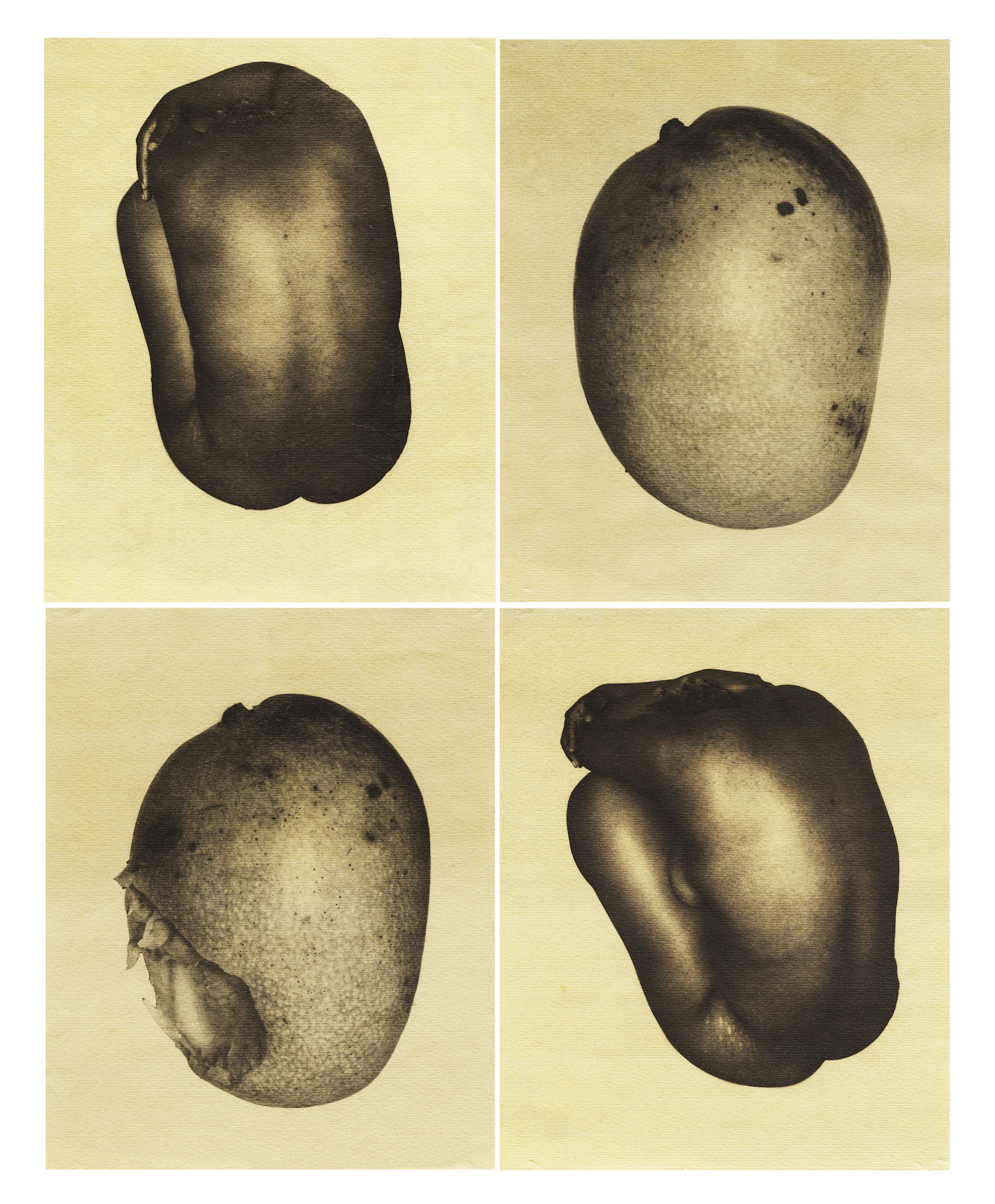

A fetishized ideal of diversity through extremes seems more the focus of “De Nue,” rather than the “apathy towards issues of race,” or “recurring anti-black acts of intimidation” its statement describes. Regardless of the medium, the concepts explored by the exhibition consistently hit the theme of challenging what it means to be a black artist.

To focus on a handful of standouts, Amina Ross, André Fuqua and Derrick Woods-Marrow are all mesmerizing for completely different reasons. In Ross’ case, the three-screen video installation “G(u)ILDING: Courtney and Tesh” features black women applying glitter makeup from head to toe while the frames snake and switch from person to person. It is one of the few pieces in the show that requires active rather than passive attention from the viewer.

The other is Woods-Marrow’s: a series of Polaroids and prints that alternate between clearly-defined and implied subjects. “Casey — 3251 Photos — iPhone 6,” which is essentially a faded-out dick pic, sits next to “Two Boys Playing in the Dark and Nothing More … I Promise,” which is exactly as described, and as a result is earnest and beautiful. “Doug (Top) and Random Guy (Bottom),” and “Choke Me” are so well-arranged that they seem like companion pieces. A man playing in balloons ends with a man with a rope around his neck — for pleasure? For the purpose of ending his life? The middle five photos in this loose series — including a man cradling a giant red penis and a spit roast conjured from images of Legos — somehow manage to keep the intent ambiguous.

After slipping on a set of headphones (placed alongside a lacquered-on legal contract), viewers will be shocked to discover that the thread that ties all of these elements together is retribution. The photos used by Woods-Marrow were obtained legally through contract by men he was sleeping with. By using people’s photos to show what individuals are interested in sexually, he is intent on calling attention to both white dismissal and the fetishizing of black people as sexual objects — a paradigm that, he implies, essentially boils down to white supremacy.

Meanwhile, Fuqua garners a multitude of subtexts in his careful positioning of sculptures. “Blossom” features three stenciled silhouettes of a single black face rotating back about 45 degrees so as to resemble an angel, or a black life being lowered into a grave.

“Seal”— an all-black likeness of the American flag — is also pertinent for what it shows, and what it doesn’t show. Fifty repeating likenesses of a black face replace the stars — immediately calling attention to representation, or lack thereof, in the United States. This is a bizarre juxtaposition with the black stripes of the flag: Though the structure is visible, the monochrome nature seems to be implying a perception of colorblindness. Next to its indented field of stars, it is a grim irony.

In a show filled with pieces that merit multilayered interpretations, something more overt like Itunuoluwa Ebijimi’s “The Black Pin-up Project” doesn’t hold up as well. The use of literal thumbtacks rather than traditional framing is a nice touch, but this series of men dressed as women (or men that identify as women, or women who identify as men, etc.) in various stages of nakedness seems easy — almost cheap. Maybe that’s the point.

Also head-scratching is Da’Niro Elle Brown’s “excerpt six.” Does a man draped in a burgundy cloak and covered in oats have any real significance? That he is rotating, crouching and writhing in an assembled pipe structure resembling a jungle gym is interesting enough, but does it contribute at all to the debate about the role of the black artist in society?

Artistic purity may not be the same as excellence, but to advocate for such a principle in a society in which one drop of black blood has historically been considered tainting seems notable enough.

“De Nue” is on view in the LeRoy Neiman Center Gallery, Gallery X and the Flaxman Library until September 25, 2016.